The UAW’s Strike Win on Plant Closures Is Too Rigid

ANALYSIS

Automotive labor negotiations have always contained contentious issues—ever since General Motors and the United Auto Workers union established the first UAW contract in 1937. By 1941, even Harry Bennett, the notorious head of Ford’s security agency, could not keep the UAW from being recognized as the legitimate representative of Ford workers.

Since then, contract negotiations have focused on two major areas: wages and benefits, most notably heath care and cost-of-living adjustments, and various forms of employment guarantees.

Wage increases, such as those the UAW fought for and won in this year’s negotiations, are certainly justified when companies are making significant profits. Well-paid workers and a safe working environment help boost productivity.

Unfortunately, serious problems develop when the union tries to do a job that should be left to operating executives. Assembly capacity decisions should be outside the purview of labor, especially during periods of rapid industry transformation.

The new UAW contract stipulates specific product placements in plants, and the right to strike over plant closures during the life of the contract. These capacity constraints could thwart the desire to fill battery-electric vehicle capacity.

A High-Cost Environment

In the 1980s, the negotiated Jobs Bank program set the expectation that jobs were secure, and that automakers would pay union members for not working if technological disruptions created layoffs. The program created a high-cost environment for GM and warned Asian and European manufacturers to stay away from the Midwest (and unions). The program was eliminated during 2009 as part of securing pre-bankruptcy federal loans.

The North American manufacturing landscape is much different today than it was in the 1980s. Competition in the battery-electric sector is disrupting the mix of labor and capital in vehicle assembly and battery production. Non-union Asian and European manufacturers have added 10 plants in North America since 2014, while the number of assembly plants with UAW representation has remained flat.

This new wave of transformation has just started, with battery-electric capacity expansion exploding through 2027. A sizable portion of added capacity will be at new sites in the South or in Mexico. Realistically, the manufacturing footprint is shifting away from unionization. Yet this is not a wage differential problem for the Detroit 3. It is a potential flexibility problem if unions block capacity adjustments moving forward.

Daunting Uncertainty

The transition to battery-electric vehicles is difficult enough without the addition of the UAW’s capacity alignment restrictions. Pricing and profit uncertainty within the sector is daunting, dealers seem reluctant to go all-in on the vision and the required infrastructure to ease consumer’s range anxiety will take multiple years to develop. Additionally, proposed CO2 and emission standards could add additional costs if manufacturers do not sell enough zero-emission vehicles.

Manufacturers will need flexibility when transitioning from ICE-dedicated plants to dedicated BEV capacity. Rationalization is mandatory given the potential price pressure that will come from excess capacity in North America. The production volume for total light vehicles is a fixed amount. Supply does not create demand. Thus, the more manufacturers implement product and marketing strategies to fill BEV capacity, the more they will be forced to reduce ICE capacity.

You can see this turmoil in the market today. Current demand and supply disruptions have forced manufacturers to close BEV plants for extended periods of time, like GM’s Orion plant transition in Michigan and the Ingersoll plant in Ontario. Both shutdowns were unforeseen one year ago. Moving forward, the disruptions will be more extensive. These disruptions—including permanent closures or elimination of shifts—need to be managed without the threat of a strike hanging over the decisions.

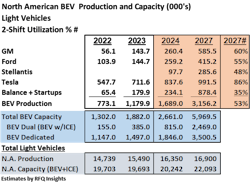

Excess capacity in the BEV sector will get worse moving forward. This situation was not a secret prior to the start of negotiations. Based on published announcements, North American BEV capacity will increase to 5.97 million units by 2027, up from 1.9 million today. Unfortunately, North American BEV production only grows to 3.16 million units. This generates a troublesome 53% capacity utilization rate, a reflection of overestimating BEV demand. The lowest utilization will exist at startups trying to capture North American share.

Prior to the new contract, it appeared as if ICE capacity would be reduced by inserting BEV models into existing facilities, eliminating shifts or closing plants. Manufacturers must have realized that waiting for the next 17+ million production year in North America was a bridge too far and began looking for ways to reduce capacity. At least three union plants should have been candidates for closure. But that did not happen. Instead, Ford added their Blue Oval plant, eight BEV plants were announced by EV startups and Tesla piled on with a plant in Mexico.

Strategies that could fill unprofitable BEV capacity will only expose more problems at ICE plants. Excess capacity will exist either with BEV plants being at full capacity or with the status quo.

Against this production-supply excess, the UAW contract was signed: Higher wages and benefits were justified. A clause that allows the UAW to strike if a plant is closed seems counterproductive. The UAW also touted that they ensured new products for other plants. Worst example: Stellantis agreed to reopen the Belvidere plant when they had sufficient capacity elsewhere to produce a new pickup. These capacity-transformation inhibitors will postpone rationalization and result in excess cost at UAW facilities.

Ideally, unions should not confuse the roles of labor and management. Labor is responsible for providing productive work for a fair wage and benefits. Management’s job is to pay competitive wages, ensure a safe working environment and make strategic decisions on “gotta-have” products and overall capacity.

The union feels they won by restricting management’s capacity flexibility. The unintended consequences of that win may be severe if the transformation requires a strike at every turn, or if excess structural costs lead to darker scenarios. Carlos Ghosn, former chair of Renault-Nissan, once said about the auto industry, “failure is not forbidden.” The UAW should post that quote in the union hall as a reminder when gathering to vote on future strike decisions.

Warren Browne is president of RFQ Insights and is an adjunct professor of economics and trade at Lawrence Technological University. Browne retired from General Motors in 2009, after 39 years of service. From 1991 to 2009, he held senior executive positions at GM.

About the Author

Warren Browne

President, RFQ Insights

Warren Browne, president of RFQ Insights, has held senior executive positions at General Motors Corp, working in six countries over a 40-year career with the automaker. He is currently an adjunct professor of trade and economics at Lawrence Technological University.