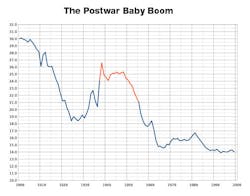

For many years, demographers have been predicting that this current decade would bring a big surge in the number of baby boomers retiring from the workforce. Now, in the last couple years, that long-anticipated outflux has started to happen. Employees of U.S. manufacturing companies have been retiring in noticeably larger numbers as the eldest baby boomers reach age 65. And their employers are starting to feel the impact of those valued veterans walking out the factory door for the last time.

But there are smart manufacturers across the U.S. who heeded the workforce experts' warnings and took steps to prepare for the onset of the baby-boom retirement bubble. For those companies, the en masse departure of longtime employees, while still being felt, isn't hitting as hard.

See Also: Manufacturing Workforce Management Best Practices

This article examines three U.S. manufacturing companies that prepared well for the boomer exodus: Huntington Ingalls Industries, The Raymond Corporation, and Hypertherm. It explains how these companies laid the groundwork for their preparations, how they carried their plans out, and how they're faring as a result.

First Responder

Huntington Ingalls Industries (IW 500/157) was forced to deal with the boomer drain earlier than most U.S. manufacturing companies. The Newport News, Va.-based shipbuilder, which makes nuclear aircraft carriers and submarines for the U.S. Navy, got socked twice in the last two decades with big outflows of veteran employees, first in the late 1990s because of U.S. defense budget cuts, then again in 2005 with the catastrophic gut-punch known as Hurricane Katrina.

"We've been dealing with this workforce demographic issue in the aerospace and defense community for a long time, really since the late '90s," says Bill Ermatinger, corporate vice president and chief human resources officer at Huntington Ingalls. "We saw this starting to happen well before most manufacturers in the United States."

After federal spending cuts forced hiring freezes and layoffs on aerospace and defense manufacturers in the 1990s, Huntington Ingalls' leaders knew they had a major task on their hands figuring out how to fix the demographic hole that earlier exodus had left in its workforce. The company's leadership team had set to work repairing that hole in the early 2000s when -- boom -- Katrina hit.

"The day after Katrina happened, down at our Gulf Coast facility, basically every employee that could retire said, 'I'm out of here. I'm done with hurricanes,'" Ermatinger recalls. "So now the already-bad demographic issue we were facing got accelerated on us. We thought we were going to have more time to deal with it, but Katrina accelerated it."

The demographic double-whammy left Huntington Ingalls with a very inexperienced employee mix: 72% of its workers with less than 15 years of experience; 24% with 15 to 25 years; and just 4% with greater than 25 years. Suddenly, knowledge management became crucial to the company's continued success.

Huntington Ingalls' leadership team responded by making major investments in training. In addition, they began studying the company's work crews to isolate the factors that made some crews successful and others less so, and they learned that having an effective, well-trained foreman -- regardless of that person's age -- was far more critical than having veteran leadership per se. So they began to put greater emphasis on leadership training -- and training of foremen in particular -- within the company's overall training mix.

"That was a real eye-opener and game-changer for us," Ermatinger says. "As a result, we really started to put our energy into accelerating the training of our first-line leaders. We've concentrated on that, and it has made it easier to get everyone else onboard and pulling in the same direction."

The results speak for themselves, Ermatinger says.

"We're seeing wonderful performance. We're making ships of the highest quality, with a workforce that's still relatively inexperienced: 73% have less than 15 years. There's only one way to explain it: our investment in leadership development."

Training, Mentoring, Outreach

The Raymond Corporation began feeling the effect of the retirement boom two years ago, just as the eldest of the post-World War II boomers started hitting age 65. The Greene, N.Y.-based company, which makes warehouse material-handling equipment, has had 4% to 5% of its workforce retire over the last couple years. And its leaders expect that pace to continue through the end of this decade.

"It's a critical issue for us," says Steve VanNostrand, executive vice president of human resources at The Raymond Corporation. "We've clearly been having a higher level of retirements. Historically, our organization has been fortunate to have a lot of long-serviced, highly capable and competent individuals who contribute at a high level. Now, as you start to see a lot of those people retiring, obviously you need to have a plan in place to build a bridge to the next generation.

"So we're working our way through that. Every employee is critical to our organization, so the increase in retirements certainly is having an impact, and it needs to be carefully managed if we're to be successful."

The Raymond Corporation is addressing its workforce demographic challenges with a number of strategies aimed at recruiting, retaining and developing talent via individual career development plans, targeted and situational learning, and cross-functional mentoring.

"Visibility is critical to getting that line of talent coming in the front door, so we've been active with community involvement and partnerships, whether it's at the high school level, technical colleges, universities, or graduate schools," VanNostrand says.

"From there, once you've attracted the talent, the key challenge becomes how do you retain and develop it," he says. "At the end of the day, it's about enhancing the skills that will prepare you for the future. We have a particular focus on accelerating leadership skills to make sure we've got that next generation of leaders prepared as we begin to lose our more seasoned people."

That focus seems to be working: The Raymond Corporation has been growing quickly, almost doubling its workforce over the last three years, and it has been able to fill 85% of the key positions that have opened up by promoting from within.

"There are lots of ways to go about attacking this issue, to make sure you're getting top-notch people and then focusing your energy around how to make them successful over the long term," VanNostrand says. "Lots of companies do it in subtly different ways. But what really matters, what it really gets down to, is not so much the great ideas as it is focus, execution and discipline."

An Institutional Approach

Hypertherm is another company that foresaw the workforce retirement pinch coming and took pre-emptive steps well ahead of time to lessen its impact. Eight years ago the Hanover, N.H.-based maker of cutting systems for manufacturers and shipbuilders began noticing it was having trouble finding skilled machinists to operate its advanced CNC machines.

"The problem reached a critical point for us in 2006," Hypertherm CEO Dick Couch recalls. "We were projecting that in order to keep up with demand we'd have to more than double the number of machine operators on our floor. We knew it would be impossible to do that by continuing our normal process of having each new operator shadow an experienced associate on the plant floor. The process wasn't efficient enough."

Hypertherm's leadership team responded to the challenge by making a major capital investment to establish an internal training center, the Hypertherm Technical Training Institute, in 2007. The company developed what Couch calls an "immersion-style" education program aimed at taking promising high school graduates with little or no machining experience and converting them into skilled machinists over a nine-week training period.

In 2009, Hypertherm enhanced its training program by partnering with New Hampshire's community college system to enable students who complete the company's program to earn college credit toward an associate's degree and a machine tool technology certificate.

While Hypertherm created its training center several years ahead of the boomer retirement bubble to address a different but related problem, the institute's existence has certainly helped the company over the last couple years as workforce retirements have started picking up.

"We're definitely seeing the number of retirements increase, especially in 2013," Couch says. "So now we find ourselves not only having to recruit skilled machine technologists just to allow us to grow the business, but we also have to recruit to replace the people who are leaving the workforce."

Today, five years after the formation of its training institute's sponsored degree program, Hypertherm's system is so successful that in addition to meeting its own workforce needs, the company has opened the institute to other employers in a cooperative effort to boost the overall skill level of CNC machine operators in the region.

Looking at the U.S. manufacturing industry as a whole, even in the face of the ongoing boomer retirement wave that is expected to last another six to 10 years, Couch says he's confident that U.S. companies will be able to weather the storm.

| Read more about workforce demographic issues at iw.com/workforce/recruiting-retention. |

"I'm optimistic," he says. "When you hear the president of the United States talking specifically about investing in training for manufacturing -- well, we haven't heard much of that in the last 20 years. So I feel good about where we're headed."

About the Author

Pete Fehrenbach

Pete Fehrenbach, Associate Editor

Focus: Workforce | Chemical & Energy Industries | IW Manufacturing Hall of Fame

Follow Pete on Twitter: @PFehrenbachIW

Associate editor Pete Fehrenbach covers strategies and best practices in manufacturing workforce, delivering information about compensation strategies, education and training, employee engagement and retention, and teamwork. He writes a blog about workforce issue called Team Play.

Pete also provides news and analysis about successful companies in the chemical and energy industries, including oil and gas, renewable and alternative.

In addition, Pete coordinates the IndustryWeek Manufacturing Hall of Fame, IW’s annual tribute to the most influential executives and thought leaders in U.S. manufacturing history.