The Fallacy of Voice of the Customer

Within the last few years, companies have placed greater emphasis in collecting voice of the customer (VOC) to accelerate their improvement and innovation efforts.

Yet companies still create processes laden with waste and bring products and services to the marketplace that fail.

Why is that?

While customers have a key place in formulating our innovation strategy, many VOC gathering processes are flawed or misdirected.

Most companies and customers are good at articulating what they are familiar with, which leads them to focus on the functions of the existing products and solutions. In turn, that's where improvement and innovation efforts are focused too.

When products, processes or services have reached a certain maturity, though, such improvements tend to be increasingly incremental. They also tend to lead to standardized waste.

If you're able to improve the quality of a product or productivity of a service by 50% later, you have to ask: Why was all of that waste built into the process in the first place?

Instead, to really innovate with products and services, companies should look at the unarticulated needs of their customers.

The Novel S-curve

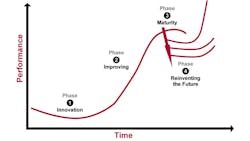

The "diffusion of innovation" pattern suggests that most improvements and innovations follow a similar pattern in the form of an "S" curve.

In broad terms, the curve suggests four phases of a performance life cycle: emergence, growth, maturity and aging.

Most incumbent businesses are not good at commercializing the next generation of S-curve.

It wasn't a candle company that commercialized the light bulb, or a slide-rule company that commercialized the calculator. While Kodak did invent the digital camera, the company was unable to capitalize on its invention.

The failure of the incumbents is not because of their lack of VOC, but because their psychological inertia and existing business models prevent them from pursuing the underlying true-customer need.

Example: Self-cleaning Windows

For example, consider a window-cleaning company that has decided to conduct a focus group to gather the voice of their customers who hire them to clean high-rise office-building windows.

These customers are likely to say they would like reliable service, low cleaning costs, superior and consistent quality of cleaning, minimal spots from detergent, minimal disruptions during office hours and safe cleaning operations. Sophisticated customers might demand that the cleaning operations be done while the offices are unoccupied at night or weekends.

On the surface, these would appear as true customer needs based on VOC.

On the other hand, if we ask these customers the purpose behind hiring the service of the cleaning company, they are likely to answer that it is for the obvious reason that the windows are dirty.

If we try to understand why they need clean windows, they are likely to confirm that it is so they can see outside and let sunlight into the room.

The purpose behind wanting to see outside through the windows could be to relax the eyes of the occupants or to provide a comfortable background while working.

While many cleaning-service companies have been using such customer feedback to improve their offerings, another company has virtually succeeded in eliminating or minimizing the need to clean glass windows.

They are trying to bring about a new generation of S-curve to satisfy the need of providing a clear view of the outside and allowing sunlight into the room without the need for cleaning the window regularly.

By taking inspiration from nature, Pilkington Glass created a "self-cleaning glass" with potential to disrupt the window cleaning industry.

After studying lotus leaves, which have a microstructure that repels water droplets and allows those droplets to pick up dirt particles, Pilkington developed a photocatalytic and hydrophilic coating for the external glass pane of windows, enabling the self-cleaning process.

The Takeaway: Look at the Job to be Done

Customers often want better ways of solving their problems, such as less disruption of office work while cleaning windows.

A "classical" improvement project would focus on such an aspect and might suggest cleaning outside office hours as a solution-a more expensive solution.

But by looking beyond just VOC, it's possible to remove the very need to solve the problem.

Underlying this deeper understanding of what customers are trying to get done is the concept of the "Job to be Done."

Professor Ted Leavitt of Harvard Business School once said, "People who buy power drills don't necessarily want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole."

The job customers are trying to get done is to make a quarter-inch hole. The current solution they are hiring is a quarter-inch drill. Focusing on the job helps companies look beyond the current solution.

In our example, classical improvement projects might have attacked the need to clean windows without disrupting office operations.

Pilkington's self-solution has worked on the job itself. Other solutions might look into the higher purpose for cleaning windows, taking into account those barriers that exist, such as the disruption of office operations.

Are there other ways than cleaning windows to provide a comfortable background while working?

Focusing on such a higher purpose could have other advantages as well. It could help bring down the costs of offices, as windows tend to make them more expensive, and it could turn more square footage into valuable office space.

In the long run, providers must think of eliminating the job altogether by addressing the higher purpose and those barriers that exist. Otherwise, somebody else stands to disrupt their business by moving ahead of them.

VOC vs. the Job

So do we stop collecting VOC?

The answer is no, of course. Instead, we should distinguish between the job customers are trying to get done and the solution they are currently hiring for that.

By not confounding the job and solution and putting the job in the context of its higher purpose and barriers, we can better observe how customers are truly struggling with their current solutions and we can better help them.