The New Manufacturing: Conquering A World Of Change

The world of manufacturing has reached a turning point. Buffeted by wave upon wave of change during the last quarter century, executives of manufacturing companies and those who advise them have redefined what it means to be a manufacturer and have developed strategies to compete under the new rules. To be sure, the catalysts of the ceaseless change -- the increasing globalization of business and the stunning advances in information technology -- have transformed every aspect of society as we know it. The very purpose of a company -- manufacturing or service -- has been turned on its ear. No longer content to be merely makers of products or providers of services, manufacturing executives now see their role more broadly, as creators of value and wealth.

For manufacturers, however, the changes have been particularly wrenching. Faced with predictions of their decline at nearly every turn, manufacturers have battled back, embracing new business rules and technologies, reinventing themselves, and re-emerging as leaders of the wealth-creating sector of society.

"Manufacturing is more exciting than ever," declares Stephen R. Rosenthal, director of the Center for Enterprise Leadership (CEL) and a professor of operations management at Boston University. "It's receiving brighter minds than ever and requires people to have more skills than ever."

It's not so much that the winds of change have ceased, but that leading companies have learned to capture their power and use it to propel growth and competitiveness.

No part of the manufacturing organization has been spared. From the factory floor to the boardroom and beyond, new ways of viewing and doing work have been implemented. Indeed, the manufacturing organization has branched out, adding to the manufacturing process its suppliers and customers. Perhaps most jarring is that each of these components of the manufacturing cycle has been integrated. No longer following a safe, slow, linear path from the R&D lab through each functional department, products are developed almost instantaneously with each group of experts contributing simultaneously.

For executive leaders, the New Manufacturing represents a complete overhaul of management and strategy. While competition attacks from every angle, executives can counter with a bewildering array of strategies and tactics. The sources of innovation are broader, says Ruben F. Mettler, retired CEO of TRW Inc., Cleveland. "If you look back to the '70s or '60s, the sources of innovation for a manufacturing operation were relatively few." Now, he says, companies can "innovate to improve their productivity and competitive position by using all the resources that they can put their hands on: not just a good distribution system, not just a good engineering department, [but] the bringing together in an innovative way the potential sources of innovation."

Is it a Revolution?

With the pace of change accelerating, revolutions in business management are declared with such frequency that most executives have become inured to them. Whether this turning point -- the New Manufacturing era -- is revolutionary is for the historians to decide. The last quarter century does, however, seem to be different from the other so-called watershed moments in two ways. First, the drivers forcing the new definition -- globalization and information technology -- go beyond manufacturing, beyond business in general, and penetrate into every corner of society much like the Industrial Revolution imposed massive changes on society.

Second, so many consultants, consortiums, and theorists seem to be agreeing for a change. Discussions of a broad-based, fundamentally different theory of manufacturing management have appeared in research studies during the last two years. Among them:

- An industry-driven collaboration led by The Agility Forum, Leaders for Manufacturing, and Technologies Enabling Agile Manufacturing last January published the "Next-Generation Manufacturing Project" report.

- Ernst & Young LLP, New York, will publish its "Connected Manufacturing Enterprise" early next year after a year-long investigation involving a panel of experts from industry and academia.

- TBM Consulting Group, Durham, N.C., last fall held its "First Annual Blue Ribbon Panel on Global Manufacturing." Made up of manufacturing leaders from around the world, the gathering "was to help define the future imperatives for manufacturing success in the 21st century."

Many strategies identified by these organizations and IndustryWeek as part of the New Manufacturing are not new -- the value of teams, partnerships and alliances, and an empowered workforce is well known. What is new is that we are reviewing the best-practice strategies developed during the last 25 years and identifying the fundamental underlying principles of successful manufacturing management.

What Is The New Manufacturing?

At the heart of the New Manufacturing is a new meaning of the term "manufacturing" -- and all things related to it. Since the Industrial Revolution, manufacturing has been defined as the work that takes place on the factory floor. Now it encompasses the entirety of the enterprise from, as CEL's Rosenthal puts it, "the supplier's supplier to the customer's customer." It incorporates every function of a company producing tangible goods from research and development to customer delivery -- and, increasingly, to the products' return to the company for recycling or disposal.

"I think most people think of manufacturing as being three things: products and process, factory operation, suppliers and vendors," says Mettler. "I would add marketing, sales, distribution, and service. I think a very critical element of all this is to think of the whole operation of a company and everything that it does."

Further, whereas the traditional definition of manufacturing was once confined to making something from raw materials by hand or with machinery, the new definition recognizes knowledge and ideas as the new raw materials. The new manufacturing company's capital is therefore its intangible assets -- organizational knowledge, ability to innovate, and value-added services -- rather than tangible assets such as factories and equipment. Likewise, the value of a product is no longer inherent in the manufactured product, but in the value-added design and service that comes with the product.

"As we move to a much more knowledge-based economy or technology-driven economy, it's no longer profitable just to ship a piece of metal out the front door and it arrives at the other end," says Graham Vickery, industry analyst for the Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development (OECD), Paris. "What you're doing now is shipping some sort of component that requires things like support services, or advice, or design skills, or engineering know-how to actually use at the other end."

Adds Rosenthal: "It's almost anachronistic to just talk about manufacturing as your base."

Management expert Peter F. Drucker takes this point further, redefining manufacturing as the systematic process of production -- whether the end product is a "thing" turned out in a factory, an "intangible" such as software, or a "service" such as a mutual-fund share. Behind Drucker's new definition once again looms the specter of the marginalization of the manufacturing sector as a driver of the economy. But first, the complete definition of the New Manufacturing.

A dictionary definition of the New Manufacturing might read:

n. An era in manufacturing history during which manufacturing companies rethought and remade virtually every aspect of the way they were organized, managed, and operated: characterized by increased, intense global competition; rapid advances in and adoption of information technology; increased focus on value creation for the shareholder and the customer; and a heightened state of uncertainty.

But that definition only scratches the surface. No description of the New Manufacturing would be complete without a discussion of its origins and the factors that contributed to its development.

The Origins

While the consensus finds that increased competition from globalization and information technology forced companies to change, a specific triggering event is hard to pin down: Was it the invention of the transistor or, later, the personal computer? The development of the first Web browser and advent of the Web as a business tool? The end of World War II and the subsequent successful entry of the Japanese into manufacturing? The rise of democracy throughout the world? The growing strength of Wall Street and other financial markets or, more specifically, the shareholder? The growing strength of the customer?

Doubtless each of these events and others have had their effect on the business climate. For manufacturers, however, one event stands out, says Joseph R. Juran, a leader in the quality movement: The entry of Japanese manufacturers as worthy competitors in the late 1970s. Inextricably linked to the end of the war and other historical circumstances, the arrival of the Japanese and the quality revolution they ignited led to the dismantling of several fundamental tenets of manufacturing management. Among them:

- Quality: In the New Manufacturing, high quality at a low cost and continuous improvement are givens, replacing the Industrial Revolution-era beliefs that high quality is linked to high cost and that an irreducible rate of defects is inherent in all manufacturing processes.

- Production strategy: Companies now focus on where they add value to the production process, shedding the parts that can be done more effectively by partners. Discredited is the idea that a company must own the entire production process to be competitive. Further, just-in-time or lean manufacturing replaced the notion that a company should maintain large inventories to buffer variations in the production process. And agile, flexible, customized production replaces the old notion of mass production and economies of scale. As a result, manufacturing equipment today is necessarily programmable for maximum flexibility and to execute many production steps, rather than being specially designed for a particular production step.

- The workforce and work practice: The New Manufacturing workforce is high-skilled and empowered. It's expected to contribute to the continuous improvement of product and production process improvement. Workers are multiskilled and work easily in cross-functional work teams, eschewing the functional silos of years past. Work practice is thus organized and conducted flexibly in an as-needed sequence with little or no supervision. Gone are the days when a team of managers dictated and closely supervised a supposedly organized, systematic production sequence with no input from the line worker. "Now the idea is," says Juran, "let's use the heads of the people instead of just their arms and feet."

- Organization: Entrepreneurial, horizontal organizational structures -- where information is shared liberally up, down, and across the organization -- have replaced the vertical command-and-control model. In addition, no one "right" organizational model dominates in the New Manufacturing era, as the hierarchical model dominated during the Industrial Revolution. Further, focus on core competency and value contribution pushes the organizational structure outside the traditional boundaries to include myriad partner and alliance relationships that "couple and decouple" quickly based on market needs.

Business Environment

The increased emphasis on continuous improvement has collided with an increasingly globalized world fanning the flames of competition and the need for constant change.

"The time frame for that incessant change and continuous revolution is shortened, because the American economy has gotten so much better, barriers have been taken down internally to competition, and because of the removal of barriers to external competition," says John Snow, chairman, president, and CEO of CSX Corp., Richmond, Va. "What that all amounts to is that whatever you did yesterday that made you successful, somebody else is copying it, using it as a benchmark. They find out what you're doing and they figure, well, if they can do it that well, we'll do it better. All of that leaves business in a continual state of reinventing itself and in a continual state of turmoil."

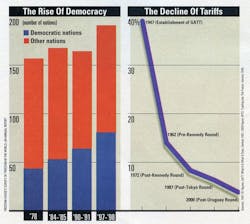

At the same time, democracy is expanding around the world, opening new markets -- and bringing new competitors to the table. "In the last 10, 15, 20 years, the world has just exploded," explains Lawrence S. Davidson, director of the Global Business Information Network at the Indiana University Kelley School of Business in Bloomington. "What used to be a bunch of dictatorially run closed economies have all of a sudden changed, and they want to do business."

To be a global player in this new business environment takes on new meaning. In the New Manufacturing, globalization goes beyond merely exporting and beyond having production capacity in other countries. To be a truly globalized enterprise, a company must have productive assets -- that is, local infrastructure and local added value -- in multiple countries. "We make sure that they understand how to do things, help them design locally, and then they can start exporting to countries we couldn't dream of before because they have a lower cost level," says Gran Lindahl, president and CEO of ABB Group, Zurich, Switzerland.

By having high-value-added operations in multiple countries, he adds, "I have several choices, and I try to optimize. How can I get the volume? How can I get the best for the company, for the shareholders, for our customers? I can combine financing from several countries in a package by taking components and products from several countries, and by doing that, I'm stronger."

IT's Impact

The use of information technology goes hand in glove with the increased emphasis on continuous improvement and an expanding global economy. No longer only an enabler of new business strategies, IT is influencing business strategies as executives grab for every competitive edge and new market. "Now, because of technological change in transportation and telecommunications, all of a sudden some things are feasible that never were before," says Davidson. "You can do business abroad, open up factories abroad, buy other companies, and you're generating economies of scale by greatly increasing the size of your market."

Perhaps more important, advances in information technology have caused companies to reorganize the way they do business.

"Now, you make information and data available in one database that's commonly available throughout the company for anyone who needs it to do a task," says ABB's Lindahl. "You just put it in once, and you have it everywhere. . . . We have just started this evolution into the true networking society. People call it the information society; I call it networking because what you do is connect so many varied disciplines and expertise . . . that you see there's one body, one network."

Computerization, beginning in the late 1960s, allowed more company data to reach Wall Street more quickly, Lindahl points out. Financial data "went from one-year consolidations to semiannual consolidations, then to quarterly, then to monthly, and now [data are available] almost weekly."

"It used to be that people were pretty well satisfied with an expected return that provided some kind of a premium over the long-term bond rate," adds Paul Lego, former chairman and CEO of Westinghouse Electric Corp., Pittsburgh. "But I think today the expectation for continuous improvement and growth and shareholder value is there. And the shareholder seems to be very quick in terms of turning away from those operations that don't produce these results on a continuous basis."

Meanwhile, says Lego, customers "look for instantaneous deliveries -- they want to minimize the inventory they have to carry. They go worldwide from a purchasing standpoint looking for the best quality, lowest price, best service that they could possibly get anywhere." Increasingly, he adds, customers are allowed to direct-order from both warehouses and factories, have direct access to inventory, and they can direct input to manufacturing scheduling systems.

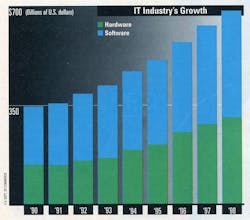

The IT Industry Influence

Just as the automobile and steel industries will forever be considered Industrial Revolution-era industries, information-technology industries -- the computer and telecommunications industries -- will be inextricably linked to the New Manufacturing era. Many people already have dubbed this time period the Information Age, fulfilling the prophecy of Alvin Toffler's The Third Wave (1980, William Morrow & Co.). But from the manufacturer's point of view, the IT industry hasn't supplanted manufacturing -- it has revitalized manufacturing. The success of the IT industry is a manufacturing success story. True, as many people argue, it's the intangibles that people are buying when they buy a cell phone or a computer, but where would those intangibles be if no company could manufacture them?

"If we didn't get progress in the products that support the digital age, the digital age would stop," asserts CEL's Rosenthal. "If Intel stopped developing new advanced chips, manufacturing them, and figuring out how the heck they get more and more onto a chip and make those chips at high quality, we'd come to a halt. You can't be in a digital age if you can't move all those bits and bytes around, so what's happening is that the excitement and the investment and the growth are in different kinds of manufacturing."

A look at "The Emerging Digital Economy," a report recently published by the U.S. Dept. of Commerce, supports Rosenthal's view. The report demonstrates that IT is the new driver of the economy and estimates that manufacturers of IT products -- computers, semiconductors, telephones, and the like -- make up 44.7% of the digital economy in the U.S. this year.

It's as if we're defining the "ages" now not by how work gets done, but rather the raw materials that drive manufacturing, much like the Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages.

Why Manufacturing Matters

Still, conventional wisdom has it that we are in the post-Industrial Age, that the service industries -- many of them IT industries -- are driving wealth creation, relegating the manufacturing sector to the backseat. Those who support this line of thinking point to statistics showing that manufacturing employment and contribution to GDP have declined. Manufacturers counter that those very statistics instead tell a manufacturing success story. "Manufacturing isn't disappearing," asserts Rosenthal, "it's just adding value in with less investment required."

Productivity statistics from the OECD prove Rosenthal's point. Manufacturing productivity's average annual growth rate in OECD countries increased by 1.5% from 1985 to 1995, far outstripping the service sector's 0.8% rate.

Though OECD statistics show manufacturing's contribution to business-sector value-added in current prices has declined slightly over the last decade, Vickery nevertheless states flatly, "Manufacturing is still very important in all economies for two reasons: productivity growth and research and technological development." In OECD countries, he says, statistics show manufacturing accounts for 84.6% of research and development.

"We would argue that a fairly high share of all growth and the advancement of the society in general comes from technological advance," explains Vickery. ". . . Technological development [leads] to the new and improved services and processes to produce things. This means we have more output per employee, which determines how wealthy we all are in the long run. That is simplifying things, of course.

"It depends a little on how you measure [the contribution of manufacturing]. If you look at it in terms of value added or total GDP, then manufacturing is declining less than if you look at the share of employment, simply because productivity in manufacturing is much higher than productivity in service. That's value added, which is a better measure of the true contribution. . . . A whole other view of [manufacturing] is how it has enriched the lives of consumers and companies who can do things they never could have done before and still afford it."

For manufacturing executives in the New Manufacturing era, the debate about the importance of manufacturing to the economy is one they have heard before. Once again they are defying those who declare manufacturing dead or insignificant. They have created a new vision of manufacturing, have deployed new, innovative strategies grounded in that vision, and have focused on the task at hand: creating wealth in an increasingly competitive, complex, fast-changing, global business environment.

About the Author

Patricia Panchak

Patricia Panchak, Former Editor-in-Chief

Focus: Competitiveness & Public Policy

Call: 216-931-9252

Follow on Twitter: @PPanchakIW

In her commentary and reporting for IndustryWeek, Editor-in-Chief Patricia Panchak covers world-class manufacturing industry strategies, best practices and public policy issues that affect manufacturers’ competitiveness. She delivers news and analysis—and reports the trends--in tax, trade and labor policy; federal, state and local government agencies and programs; and judicial, executive and legislative actions. As well, she shares case studies about how manufacturing executives can capitalize on the latest best practices to cut costs, boost productivity and increase profits.

As editor, she directs the strategic development of all IW editorial products, including the magazine, IndustryWeek.com, research and information products, and executive conferences.

An award-winning editor, Panchak received the 2004 Jesse H. Neal Business Journalism Award for Signed Commentary and helped her staff earn the 2004 Neal Award for Subject-Related Series. She also has earned the American Business Media’s Midwest Award for Editorial Courage and Integrity.

Patricia holds bachelor’s degrees in Journalism and English from Bowling Green State University and a master’s degree in Journalism from Ohio University’s E.W. Scripps School of Journalism. She lives in Cleveland Hts., Ohio, with her family.