The Post-Industrial Service Economy Isn’t Working for the Middle Class

IndustryWeek's elite panel of regular contributors.

In a 2018 blog item, “The Rise of the Service Economy” the St. Louis Federal Reserve asked, “Is this bad? Of course not. Indeed, goods can now be produced with fewer people—thanks to technological progress and automation … and perhaps also automatization. This transformation allows the economy to direct more of the labor force to enhancing our lives in other ways, such as tourism and entertainment, advanced health care, and anything related to the Internet, all of which are services that were either nonexistent or luxuries in 1939.”

Well, like it or not, we are now in the post-industrial service economy. If you have a college degree or some significant skills, you probably have a good chance to claw your way into the credentialed elite. But if you are among the 56% of workers who have a high-school diploma or less, you may be struggling to make ends meet. Millions of workers in this category feel that something is very wrong in our economy. When you look deeper into the economy, you will find that people cannot find jobs with decent pay and benefits, cannot afford to buy a home, have children or afford college. They are frustrated, angry and worried about their future.

So, What Happened?

Since 1979, America has lost 7.5 million manufacturing jobs (36%). According to the Economic Policy Institute, 5 million of these jobs have been lost between 2001 and 2021, after China was allowed into the WTO.

Wages and benefits from these manufacturing jobs gave adults with a high school education a path into the middle class. Unfortunately, they have been chiefly replaced by lower-wage service jobs.

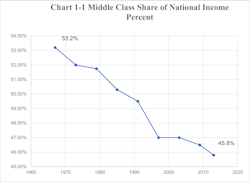

The following chart shows how the middle class share of national income has been declining for the last 50 years. (Source: U.S. Census Bureau data)

Most working people feel the pressure of growing inequality but seem to be confused on how it happened and why. The EPI says that increasing inequality stems from two factors: a surge in compensation for the 1%, and “the erosion of labor’s share of income and the corresponding growth of capital’s share.

Inequality and the Shift of Wealth

The great shift in wealth started in the 1980s, but it really accelerated at the start of the Great Recession of 2008/2009. This shift has been a big factor in the decline of the middle class and the rise of serious economic inequality. Table 1-2 shows that below the 60th percentile, income and net worth are poor, and the bottom 40% have a negative net worth. The gap between the haves and have-nots has widened at an accelerating pace.

What seems to stoke anger is that the tremendous gains in wealth by the 1% were at the expense of the middle class, and that has led to the growth of inequality.

Will the Service Economy Create Enough Good Jobs?

The real issue that the economists never seem to address is this: Will there be enough family wage jobs to allow all members of the middle class to raise families? Will the new jobs pay enough to maintain middle-class living standards or to keep the gap between the "haves" and "have-nots" from increasing?

The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects there will be a total 27. 1 million jobs (63%) in 2031 with an average wage of $40,698 per year, and a total of 16.7 jobs (37%) with an average wage of $107,988 per year. With few exceptions, almost all of these higher-paying jobs are white-collar, requiring a college degree or advanced skills.

The government and media tend to focus on telling the employment story in terms of the total number of jobs available and the unemployment rate. This is an incomplete and often inaccurate description of health of the economy because it refers to quantity, not quality of jobs.

The job quality index

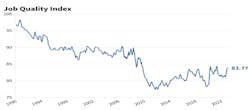

A new economic indicator called the U.S. Private Sector Job Quality Index (JQI) shows that the economy has produced a lot of jobs but they are increasingly “low quality” service jobs. The JQI chart (Source: Coalition for a Prosperous America) shows that the quality of new jobs has been decreasing for 30 years.

Table 1-3

Over the past three decades, the job quality index has significantly decreased, moving from a JQI level of 94.9 in 1990 to 84.0 in 2022. Since 1990, America has cumulatively added some 20 million low-quality jobs, versus around 12 million high quality ones”. The reason is obvious. “Lost manufacturing jobs were replaced by lower-wage/lower-hours service jobs.

In short, the U.S. economy has shifted towards creating more bad jobs than good jobs. This does not bode well for workers with a high-school diploma or less.

A paper on “The Persistence of the China Shock,” by David Autor and David Dorn, says that of 722 U.S. regions analyzed, 223 of them, or 32.8%, suffered absolute declines in real per capita income. This means that “the open door for Chinese imports reduced the incomes of one third of the U.S. public.” They go on to say that “trade with China is effectively a vehicle to transfer income from working class in the heartland to the affluent, who live mostly on both coasts.”

If a person loses their manufacturing job ($26.04 average wage, 40.7 hours per week) and has a high-school diploma, they are likely to find a job in one of the following industries (data from the BLS, April 2023):

- Leisure and hospitality industry, which has 14.7 million non-management employees earning $21.04 an hour and working an average of 25.8 hours per week.

- Administration and support, which has 9 million jobs earning an average of $24.63 per hour and working 34 hours a week.

- Retail, with 2 million jobs earning an average of $23.83 per hour and working 29.9 hours a week.

- Warehousing and transportation, with 5.2 million jobs earning an average of $28.86 per hour and working 38 hours a week.

Yes, we are in the Post-Industrial Service Economy, and the assumption that living standards will improve from one generation to the next is in question. The big economic question today is, “Can we transition from a manufacturing economy to a service economy and still provide enough good jobs to raise the standard of living for most workers?”

There is growing proof that the post-industrial service economy is not going to provide the wages and living standards people need, or the economic growth in the economy promised by many economists. The smooth transition to the service economy has become a very rough road and has created many losers—and unlike in Western Europe, in America the government does little to take care of the losers.

If you are part of the 1%, life is good, and you’re probably interested in supporting legislation that maintains your position. But if you are in the middle or lower class, or if you are among the 91 million workers (56% of all workers) who do not have a college education, then the future probably looks bleak, which has led to general unrest in working America.

Reshoring Manufacturing Jobs

President Biden has said he wants to create 5 million manufacturing jobs and build a stronger domestic industrial base to ensure that the future is made in America for American workers and families. Reshoring manufacturing jobs is doable but to create 5 million new manufacturing jobs will require the government to act against currency manipulation, devalue the dollar by 20% and enforce trade laws.

Michael Collins is the author of a new book, “Dismantling the American Dream: How Multinational Corporations Undermine American Prosperity.” He can be reached at mpcmgt.net.