The Competitive Edge: Can the US Maintain its Innovative Capacities?

With U.S. unemployment at or above 7.8% since his first inauguration speech, President Barack Obama has spent a great deal of time touting manufacturing as a key to new job creation. But as Robert Reich, Lawrence Summers and others from the president's own party have pointed out, the 21st-century factory sector is limited in its ability to create widespread employment opportunities. Manufacturing has gone from 30% of the total workforce in 1950 to under 10% today. Even assuming a new manufacturing renaissance, we'll never see a quarter of the workforce in factory-related jobs again. Neither will any other advanced economy.

See Also: Manufacturing Innovation & Product Development Strategy

Make no mistake, though: manufacturing remains a vital part of any plans for economic revitalization. Innovation is widely recognized as key to increasing productivity and raising living standards, and -- with three-fourths of private R&D investment stemming from manufacturers -- no sector contributes to innovation like the factory sector.

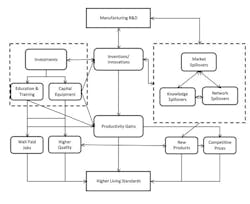

It's been a decade since economist Joel Popkin offered his groundbreaking study that connected the dots between manufacturing R&D, innovation and increased living standards (updated in 2010). But those links are even more valid today. As the accompanying chart shows, wealth creation starts with an idea that spurs manufacturers to invest in research and development, which leads to innovations. These stimulate manufacturers to invest in human and physical capital, and they also create "spillovers" that benefit other parts of society -- from competitors to suppliers to other economic sectors. All of this leads to productivity gains and, in turn, to higher paying jobs, higher quality products, new products and processes, and more competitive pricing. Ultimately, citizens experience higher living standards.

But which citizens? Two decades ago, the consensus among economists was that it didn't matter where the world's factories were located -- American citizens could continue to enjoy higher living standards without significant production taking place here. The consensus has since shifted and the academic and political worlds are gaining a better understanding of the links between domestic manufacturing and economic growth.

Helping Industry Innovate

In their important new book "Producing Prosperity," Gary Pisano and Willy Shih argue that policymakers need to focus on helping American manufacturers innovate. The two Harvard Business School professors observe that manufacturing innovation is most likely to occur within America's "industrial commons" -- communities of manufacturers, suppliers, research labs and skilled talent in geographic proximity that support each other and lay the foundation for such innovation. Such clusters can provide a nation its competitive advantage.

Unfortunately, over the past two decades, these industrial commons have started disappearing from our shores. From machine tooling to LED lighting and LCD displays to rechargeable batteries to semiconductor production, much of this nation's technological knowledge and infrastructure has left for Asia. When such industrial networks vanish, we lose both the production and, eventually, the innovation associated with their industries.

This depletion isn't natural or inevitable. Rather, as Pisano and Shih observe, much of it is the consequence of a multi-decade "high stakes experiment" to see if our economy could prosper without manufacturing, an experiment in which both public officials and private-sector leaders have played a hand.

The experiment seems to have come to an end, judging by the reshoring of production and new investments by manufacturers in this country. The next step is for policymakers to resolve to develop a national strategy to ensure U.S. manufacturers maintain their innovative capacities. Reviewing the policy prescriptions of Pisano and Shih would be a good place to start.

About the Author

Stephen Gold

President and Chief Executive Officer, Manufacturers Alliance

Stephen Gold is president and CEO of Manufacturers Alliance. Previously, Gold served as senior vice president of operations for the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) where he provided management oversight of the trade association’s 50 business units, member recruitment and retention, international operations, business development, and meeting planning. In addition, he was the staff lead for the Board-level Section Affairs Committee and Strategic Initiatives Committee.

Gold has an extensive background in business-related organizations and has represented U.S. manufacturers for much of his career. Prior to his work at NEMA, Gold spent five years at the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), serving as vice president of allied associations and executive director of the Council of Manufacturing Associations. During his tenure he helped launch NAM’s Campaign for the Future of U.S. Manufacturing and served as executive director of the Coalition for the Future of U.S. Manufacturing.

Before joining NAM, Gold practiced law in Washington, D.C., at the former firm of Collier Shannon Scott, where he specialized in regulatory law, working in the consumer product safety practice group and on energy and environmental issues in the government relations practice group.

Gold has also served as associate director/communications director at the Tax Foundation in Washington and as director of public policy at Citizens for a Sound Economy, a free-market advocacy group. He began his career in Washington as a lobbyist for the Grocery Manufacturers of America and in the 1980s served in the communications department of Chief Justice Warren Burger’s Commission on the Bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution.

Gold holds a Juris Doctor (cum laude) from George Mason University School of Law, a master of arts degree in history from George Washington University, and a bachelor of science degree (magna cum laude) in history from Arizona State University. He is a Certified Association Executive (CAE).