10 Principles of Organization Design

A global electronics manufacturer seemed to live in a perpetual state of reorganization. A new line of communication devices for the Asian market required reorienting its sales, marketing and support functions. Migration to cloud-based business applications called for changes to the IT organization. Altogether, it had reorganized six times in 10 years.

Suddenly, however, the company found itself facing a different challenge. Given the new technologies that had entered its category, and a sea change in customer expectations, it needed a new strategy. The CEO decided to shift from a product-based business model to a customer-centric one. That meant yet another reorganization, but this one would be different. It had to go beyond shifting the lines and boxes in an org chart. It would have to change its most fundamental building blocks: how people in the company made decisions, adopted new behaviors, rewarded performance, agreed on commitments, managed information, made sense of that information, allocated responsibility, and connected with each other. Not only did the leadership team lack a full-fledged blueprint—they didn’t know where to begin.

This is an increasingly typical situation. In the 18th annual PwC survey of chief executive officers, conducted in 2014, many CEOs anticipated significant disruptions to their businesses during the next five years as a result of external worldwide trends. One such trend, cited by 61% of the respondents, was an increasing number of competitors. The same number of respondents foresaw changes in customer behavior creating disruption. Fifty percent said they expected changes in distribution channels. As CEOs look to stay ahead of these trends, they recognize the need to change the organization’s design. But for that redesign to be successful, a company must make its changes as effectively and painlessly as possible, in a way that aligns with its strategy, invigorates employees, builds distinctive new capabilities, and makes it easier to attract customers.

Today, the average tenure for the CEO of a global company is about five years. Therefore, a major reorganization is likely to happen only once during that leader’s term. The chief executive has to get the reorg right the first time; he or she won’t get a second chance. Although every company is different, and there is no set formula for determining your appropriate organization design, we have identified 10 guiding principles that apply to every company. These have arisen from years of collective research and practice at PwC and Strategy&, using changes in organization design to dramatically improve performance in more than 400 companies across industries and geographies. These fundamental principles point the way for leaders whose evolving strategies require a different kind of organization than the one they have today.

Organization design should start with corporate self-reflection: What is your sense of purpose? How will you make a difference for your clients, employees, and investors? What will set you apart from others, now and in the future? What differentiating capabilities will allow you to deliver your value proposition over the next two to five years?

For many business leaders, answering those questions means going beyond the comfort zone. You have to set a bold direction, marshal the organization toward that goal, and prioritize everything you do accordingly. Sustaining a forward-looking view is crucial. That means letting go of the past.

We’ve seen a fair number of organization design initiatives fail to make a difference because senior executives get caught up in discussing the pros and cons of the old organization. Avoid this situation by declaring “amnesty for the past.” You collectively, explicitly decide that you will neither blame nor try to justify the design in place today, or any organization designs of the past. Whether or not they served their purpose, it’s time to move on. This type of pronouncement may sound simplistic, but it’s surprisingly effective for keeping the focus on the new strategy.

The blocks naturally fall into four complementary pairs, each made up of one tangible (or formal) and one intangible (or informal) element. Decision rights are paired with norms (governing how people act), motivators with commitments (governing what they feel about their work), information with mind-sets (governing how they process knowledge and meaning), and structure with networks (governing how they connect). By using these elements and considering changes needed across each complementary pair, you can create a design that will integrate your whole enterprise, instead of pulling it apart.

You may be tempted to make changes with all eight building blocks simultaneously. But too many interventions at once could interact in unexpected ways, leading to unfortunate side effects. Pick a small number of changes—four or five at most—that you believe will deliver the greatest initial impact. Even a few changes could involve many variations; for example, the design of motivators might need to vary from one function to the next. People in sales might be more heavily influenced by monetary rewards, whereas R&D staffers might favor a career model with opportunities for self-directed projects and external collaboration and education.

Company leaders know that their current org chart doesn’t necessarily capture the way things get done—it’s at best a vague approximation. Yet they still may fall into a common trap: thinking that changing their organization’s structure will address their business’s problems.

We can’t blame them, as the org chart is the most seemingly powerful communications vehicle around. It also carries emotional weight, because it defines reporting relationships that people might love or hate. But a company hierarchy, particularly when changes in the org chart are made in isolation from other changes, tends to revert to its earlier equilibrium. You can significantly remove management layers and temporarily reduce costs, but all too soon, the layers creep back in and the short-term gains disappear.

In an org redesign, you’re not setting up a new form for the organization all at once. You’re laying out a sequence of interventions that will lead the company from the past to the future. Structure should be the last thing you change: the capstone, not the cornerstone, of that sequence. Otherwise, the change won’t sustain itself.

We saw the value of this approach recently with an industrial goods manufacturer. In the past, it had undertaken reorganizations that focused almost solely on structure, without ever achieving the execution improvement its leaders expected. Then the stakes grew higher: Fast-growing competitors emerged from Asia, technological advances compressed product cycles, and new business models that bypassed distributors appeared. This time, instead of redrawing the lines and boxes, the company sought to understand the organizational factors that had slowed down response in the past. There were problems in the way decisions were made and carried out, and in how information flowed. Therefore, the first changes in the sequence concerned these building blocks: eliminating non-productive meetings (information flows), clarifying accountabilities in the matrix structure (decisions and norms), and changing how people were rewarded (motivators). By the time the company was ready to adjust the org chart, most of the problem factors had been addressed.

Talent is a critical but often overlooked factor when it comes to org design. You might assume that the personalities and capabilities of existing executive team members won’t affect the design much. But in reality, you need to design positions to make the most of the strengths of the people who will occupy them. In other words, consider the technical skills and managerial acumen of key people, and make sure those leaders are equipped to foster the collaboration and empowerment needed from people below them.

You need to ensure that there is a connection between the capabilities you need and the leadership talent you have. For example, if you’re organizing the business on the basis of innovation and the ability to respond quickly to changes in the market, the person chosen as chief marketing officer (CMO) will need a diverse background. Someone with a more conventional marketing background whose core capabilities are low-cost pricing and extensive distribution might not be comfortable in that role. You can sometimes compensate for a gap in proficiency through other team members. If the CFO is an excellent technician but has little leadership charisma, you may balance him or her with a chief operating officer (COO) who excels in this area and can take on the more public-facing aspects of the role, such as speaking with analysts.

As you assemble the leadership team for your strategy, look for an optimal span of control—the number of direct reports—for your senior executive positions. A Harvard Business School study conducted by associate professor Julie Wulf found that CEOs have doubled their span of control over the past two decades. Although many executives have seven direct reports, there’s no single magic number. For CEOs, the optimal span of control depends on four factors: the CEO’s position in the executive life cycle, the degree of cross-collaboration among business units, the level of CEO activity devoted to something other than working with direct reports, and the presence or absence of a second role as chairman of the board. (We’ve created a C-level span-of-control diagnostic to help determine your target span.)

Make a list of the things that hold your organization back: the scarcities (things you consistently find in short supply) and constraints (things that consistently slow you down). Taking stock of real-world limitations helps ensure that you can execute and sustain the new organization design.

For example, consider the impact you might face if 20% of the people who had the most knowledge and expertise in making and marketing your core products—your product launch talent—were drawn away for three years on a regulatory project. How would that talent shortage affect your product launch capability, especially if it involved identifying and acting on customer insights? How might you compensate for this scarcity? Doubling down on addressing typical scarcities, or what is “not good enough,” helps prioritize the changes to your organization model. For example, you may build a product launch center of excellence to address the typical scarcity of never having enough of the people who know how to execute effective launches.

Constraints on your business—such as regulations, supply shortages, and changes in customer demand—may be out of your control. But it’s important not to get bogged down in trying to change something you can’t change; instead, focus on changing what you can. For example, if your company is a global consumer packaged goods (CPG) manufacturer, you might first favor a single global structure with clear decision rights on branding, policies, and usage guidelines because it is more efficient in global branding. But if consumer tastes for your product are different around the world, then you might be better off with a structure that tends to delegate decision rights to the local business leader.

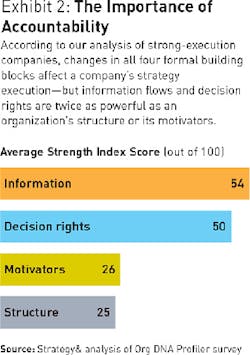

Design your organization so that it’s easy for people to be accountable for their part of the work without being micromanaged. Make sure that decision rights are clear and that information flows rapidly and clearly from the executive committee to business units, functions, and departments. Our research underscores the importance of this factor: We analyzed dozens of strong-execution companies and found that among the formal building blocks, information flows and decision rights had the strongest effect on improving the execution of strategy. They are about twice as powerful as an organization’s structure or its motivators (see Exhibit 2).

When decision rights and motivators are established, accountability can take hold. Gradually, people get in the habit of following through on commitments without experiencing formal enforcement. Even after it becomes part of the company’s culture, this new accountability must be continually nurtured and promoted. It won’t endure if, for example, new additions to the firm don’t honor commitments, or incentives change in a way that undermines the desired behavior.

One common misstep is looking for “best practices.” In theory, it can be helpful to track what competitors are doing, if only to help you optimize your own design or uncover issues requiring attention. But in practice, this approach has a couple of problems.

First and foremost, it ignores your organization’s unique capabilities system—the strengths that only your organization has, producing results that others can’t match. You and your competitor aren’t likely to need the same distinctive capabilities, even if you’re in the same industry. For example, two banks might look similar on the surface; they might have branches next door to each other in several locales. But the first could be a national bank catering to Millennials, who are drawn to low costs and innovative online banking. The other could be regionally oriented, serving an older customer base and emphasizing community ties and personalized customer service. Those different value propositions would require different capabilities, and translate into different organization designs. The tech-leading bank might be organized primarily by customer segment, making it easy to invest in a single leading-edge technology that covered all regions and all markets, for seamless interplay between online and face-to-face access. The regional bank might be organized primarily by geography, setting up managers to build better relationships with local leaders and enterprises. If you benchmark the wrong example, then the copied organizational model will only set you back.

If you feel you must benchmark, focus on a few select benchmarks and the appropriate peers for each, rather than trying to be best in class in everything related to your industry. Your choice of companies to follow, and of the indicators to track and analyze, should line up exactly with the capabilities you prioritized in setting your future course. For example, if you are expanding into emerging markets, you might benchmark the extent to which leading companies in that region give local offices decision rights on sourcing or distribution.

For every company, there is an optimal pattern of “lines and boxes”—a golden mean. It isn’t the same for every company; it should reflect the strategy you have chosen, and it should support the most critical capabilities that distinguish your company. That means that the right structure for one company will not be the same as the right structure for another, even if they’re in the same industry.

In particular, think through your purpose when designing the spans of control (how many people report directly to any given manager) and layers (how far removed a manager is from the CEO) in your org chart. These should be fairly consistent across the organization.

You can often speed the flow of information and create greater accountability by reducing layers, but if the structure gets too flat, your leaders have to supervise an overwhelming number of people. You can free up management time by adding staff, but if the pyramid becomes too steep, it will be hard to get clear messages from the bottom to the top. So take the nature of your enterprise into account. Does the work at your company require close supervision? What role does technology play? How much collaboration is involved? How far-flung are people geographically, and what is their preferred management style?

In a call center, 15 or 20 people might report to a single manager because the work is routine and heavily automated. An enterprise software implementation team, made up of specialized knowledge workers, would require a narrower span of control, such as six to eight employees. If people regularly take on stretch assignments and broadly participate in decision making, then you might have a narrower hierarchy—more managers directing only a few people each—instead of setting up managers with a large number of direct reports.

Formal elements like structure and information flow are attractive to companies because they’re tangible. They can be easily defined and measured. But they’re only half the story. Many companies reassign decision rights, rework the org chart, or set up knowledge-sharing systems—yet don’t see the results they expect.

That’s because they’ve ignored the more informal, intangible building blocks. Norms, commitments, mind-sets, and networks are essential in getting things done. They represent (and influence) the ways people think, feel, communicate, and behave. When these intangibles are not in sync with each other or the more tangible building blocks, the organization doesn’t work as it should.

At one technology company, it was common practice to have multiple “meetings before the meeting” and “meetings after the meeting.” In other words, the constructive debate and planning took place outside the formal presentations that were known as the “official meetings.” The company had long relied on its informal networks because people needed workarounds to many official rules. Now, as part of the redesign, the leaders of the company embraced its informal nature, adopting new decision rights and norms that allowed the company to move more fluidly, and abandoning official channels as much as possible.

Overhauling your organization is one of the hardest things for a chief executive or division leader to do, especially if he or she is charged with turning around a poorly performing company. But there are always strengths to build on in existing practices and in the culture. Look to these strengths—whether formal or informal—to help you fix those critical areas that you’ve prioritized. Suppose, for example, that your company has a norm of customer-oriented commitment. Employees are willing to go the extra mile for customers when called upon to do so, delivering work out of scope or ahead of schedule, often because they empathize with the problems customers face. You can draw attention to that behavior by setting up groups to talk about it, and reinforce the behavior by rewarding it with more formal incentives. That will help spread it throughout the company.

Perhaps your company has well-defined decision rights—each person has a good idea of the decisions and actions for which he or she is responsible. Yet in your current org design, they may not be focused on the right things. You can use this strong accountability and redirect people to the right decisions to support the new strategy.

Conclusion

A 2014 Strategy& survey found that 42% of executives felt that their organizations were not aligned with their strategy, and that parts of the organization resisted it or didn’t understand it. The principles in this article can help you develop an organization design that supports your most distinctive capabilities and supports your strategy more effectively.

Remaking your organization to align with your strategy is a project that only the chief executive can lead. Although it’s not practical for a CEO to manage the day-to-day details, the top leader of a company must be consistently present to work through the major issues and alternatives, focus the design team on the future, and be accountable for the transition to the new organization. The chief executive will also set the tone for future updates: Changes in technology, customer preferences and other disruptors will continually test your business model.

These 10 fundamental principles, which we have observed and cultivated while working with hundreds of diverse organizations, can serve as your guideposts for any reorganization, large or small. Armed with these collective lessons, you can avoid common missteps and home in on the right blueprint for your business.

Reprinted with permission from strategy+business, published by PwC Strategy& LLC. © 2015 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details.