Building a Culture Around Quality

Part of operating is running into ‘quality’ issues—things do not go as planned, whether through operation, raw material, planning, or plain human error. The way we address these issues sets apart good organizations from great. The majority of small manufacturers do not have a problem-solving process and as a result, see the same problems arise.

Philip Crosby, in his Quality Education System, has the best definition of quality: conformance to customer requirements. When establishing quality standards, often I see organizations provide a product or service that “over-delivers” on the customer expectation, feeling it gives an added value, when in reality, it cuts into an organization’s profit. While some people at the customer may appreciate it, at some level, it will be looked at as ‘If they can provide more than asked, their margins must be excellent.” When establishing quality metrics, whether, through Statistical Process Control (SPC) charts or other metrics, Mr. Crosby’s definition should be the guiding force.

Regardless, we will always have issues where we fall short. Systems and processes are required to be put in place to address these. Some are small, on-the-fly issues that can be resolved quickly, while others may take cross-departmental input.

Most importantly, management is responsible for creating a culture that embraces identifying quality issues and problems that arise daily. Inherently, people are reluctant to call out issues, especially those that stem from human error. Management should be the one to send the message directly to all personnel that the expectation is always to bring up any issue—that you (management) understand and expect issues to happen—and no one will be admonished for helping the organization improve. As entrepreneur Ray Dalio outlined in his book Principles, this was ingrained in his organization—with Mr. Dalio also being part of a team that would publicly send out their own mistakes to all employees, to set the example of transparency.

Once a culture of constant improvement is established, systems and processes need to be implemented to eliminate the issues permanently. Some problems are fixed quickly, and some take additional resources. One common denominator that must be asked, regardless of the size of the issue, is “What do we do to prevent this from recurring?” Without asking, answering, and implementing changes, the same issue will continue to hurt the organization.

Let’s look at the two different types of problem-solving processes:

1. Issues that arise ‘on the floor’ or during in-house production that can be addressed in the short-term. This may entail equipment-breakdown issues, process flow, raw material (or lack of), etc. Typically, the supervisor/manager will provide a ‘quick fix’ to ensure the process continues to move forward to meet customer requirements—and in the end, is verbally reported to management as to what was done to correct. And that is where it ends.

If the new process that was installed on the floor will be a permanent part of the operation, it needs to be reviewed, modified (if required), and adopted as part of the new standard operating procedure. If the organization is ISO certified, the systems must be updated.

Regardless, the changes should be put in writing by the supervisor who implemented it. This does not have to be a formal system; it could be a spreadsheet with the headlines of ‘Date,’ ‘Department,’ ‘Supervisor,’ ‘Issue,’ and ‘Actions Taken,’ for clear communication. This is especially true for multiple-shift organizations. Still, it also provides a written record that can promote the behavior and actions through the organization and also be accessed for personnel reviews.

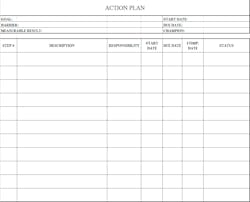

2. Long-term or multiple department issues that require much more involvement and also can be for process improvement. For example, if we are experiencing a 20% failure rate in a specific department, there may be a short-term fix to address on the floor. (more staff, more raw material, etc.). But a structured approach needs to be executed to eliminate the problem long-term. This may entail getting many departments involved—quality, production, procurement, engineering, etc.—with all having specific steps and due dates. A formal written plan should be put together, with a spreadsheet identifying roles and responsibilities in addressing the issue. Here is an example:

As outlined, multiple steps may or may not be performed concurrently. As management and the appropriate personnel and team implement each level, set up review dates to study the effectiveness.

The action plan should also include a review following implementation to ensure the issue/process improvement has met expectations. If not, another action plan is needed until the issue is successfully addressed. Whether a short- or long-term solution, each one needs to be measurable and communicated to the organization.

For example, if a short-term issue is fixed on the floor, look back at it and measure the result: If we are able to reduce the amount of scrap widgets by 5%, which averages 20 per week, calculate the increase in productivity on an annual basis, the reduced overhead cost and the average labor cost per unit and communicate what this means to the organization. Make an issue of how this is an example of how we want everyone in the organization to work and think, along with the measured results. If there is a bonus tied to performance, communicate the impact.

Whether a short- or long-term solution, each one needs to be measurable and communicated to the organization. For example, if a short-term issue is fixed on the floor, look back at it and measure the result—e.g., reducing the amount of scrap widgets by 5%, which averages 20 per week. Now, calculate the increase in productivity on an annual basis, reduce overhead cost and the average labor cost per unit, and communicate what this means to the organization. Make an issue of how this is an example of how we want everyone in the organization to work and think, along with the measured results. If there is a bonus tied to performance, communicate the impact.

On the more significant issues, perform the same cost-saving/production increase/profit results and how they will impact the organization and the opportunities it may provide—additional work with no other machinery or labor, etc.

Again, the biggest question that must be asked at the outset is, “What do we need to do to prevent this from recurring?” If we ask and effectively answer this, we will be able to realize continuous improvement.

Larry Scarborough is currently a senior project director at Cogent Analytics, and formerly a chief operating officer of a multimillion-dollar electronics hardware design firm. Larry has helped businesses to succeed working as a business management consultant to small businesses from $2 million on up to Fortune 1000 companies. His clients have included government agencies, automotive manufacturers, aluminum fabricators, and small-to-mid-market distribution and manufacturing organizations.