The Big Disconnect: Technology vs. the Real-Life Workforce

Every day in the news media there are stories about the digital revolution—how it will save American manufacturing through cost reduction and efficiency and how it is the solution to our supply chain and manufacturing problems. These high-tech solutions have names like artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, Industry 4.0, the industrial metaverse, cloud computing and machine learning—and are all supposed to lead to the creation of “smart factories.”

Implementing these digital solutions is important in the long term, but I wonder where these new workers will come from or if the promoters of these new solutions have really examined the applicants. We have not been able to find or train enough replacements for the retiring machinists, assemblers, maintenance technicians, welders and other skilled workers, when the current brain trust of skilled workers is walking out the door. So, I wonder why recruiting and training the technicians for the digital revolution will be any different.

The Skilled Worker Problem

Manufacturing has had a shortage of skilled workers for at least 30 years—and every year, it seems to get worse. Unfilled jobs averaged 760,000 per month in 2022. Even though manufacturers have raised starting wages, young people are not flocking to manufacturing with applications in hand. In fact, manufacturing is up against stiff competition from companies like Amazon, FedEx, UPS and Starbucks, who may offer better wages and training.

As of December 2022, manufacturing had 12.9 million workers. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 39% were people with four-year college degrees. That means that approximately 8 million manufacturing workers (61%) have less than a college degree and most have high school diplomas or less.

I think it is a safe assumption that to replace the workers who work on the factory floor, manufacturing will have to compete for the students coming out of high school. If they are going to be candidates for entry-level jobs, it might be wise to take a hard look at their educational profiles through standardized testing to plan for the future.

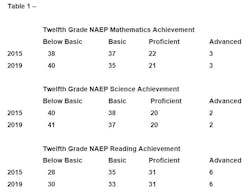

There are 26,727 high schools in the U.S. with approximately 15.1 million students. The best survey that I have found that provided insight to high school students who will be in the job market is a national test by the NAEP (National Assessment of Educational Progress). It divides student test results into four categories that are useful in trying to profile future entry-level workers.

Below basic. This category reveals a serious lack of performance, and there is little understanding of the knowledge or skills at specific grade levels. These are students who may drop out of school or did not get enough credits or pass enough tests to graduate.

Basic. This category represents a limited performance, and the students demonstrate only a partial and rudimentary understanding of the knowledge and skills of their grade. These are students who probably graduate from high school but are disengaged and may not qualify to go to a public university. They are just trying to get enough credits to get a diploma.

Proficient. These students show good performance and demonstrate competency and adequate understanding of the knowledge and skills.

Advanced. This group shows superior performance and demonstrates a comprehensive and complex understanding of knowledge and skills. They are generally students who graduate and have the credits, grades and test scores to qualify for a four-year university.

These four categories approximate the general report card grades of Below Basic – D and F, Basic – C, Proficient – B, Advanced – A.

Manufacturing needs new employees who are technically well trained and students who are above average in reading, science and mathematics. Having spent 35 years in manufacturing, I know firsthand why future manufacturing workers need to have a better education with more science and math classes to compete in the 21st century. I think the idea of getting kids more proficient in science and math is a splendid idea, but the national testing results of 12th grade students in science, reading and math are shocking. They show that in 2019, 75% of the students in mathematics, 78% of the students in science and 63% of the students in reading are below the proficiency line.

On the other hand, 22% to 25% of students score in the proficient or advanced categories and have the grades and test scores to go onto college. However, college graduates generally go to professional (white collar) jobs in manufacturing like engineering, accounting and management. They don’t usually become factory-floor workers.

The students in our high schools are not a homogeneous group. Each high school has its share of each group. I use these general groups to make the point that the recruiting of entry level workers for the factory floor will probably come from the Below Basic or Basic students who lack basic skills.

Children Left Behind

In the past, the education establishment tried to improve high school education by making teachers and education programs more accountable and measuring them with proficiency tests. It was hoped that this would drag students kicking and screaming up to an acceptable level of proficiency. But it never worked, and we still have a majority of high school students in the Below Basic or Basic categories. In fact, as the percentages above show, there has not been real improvement.

Literacy statistics are concerning as well. According to the U.S. Department of Education, 1 in 5 adults has difficulty with skills that require basic literacy—comparing and contrasting information, paraphrasing or making low-level inferences.

Literacy is also a major factor in whether adolescents graduate from high school. According to ProLiteracy, 1 in 6 high school students--about 1.2 million teens--drop out each year.

Manufacturing Opportunities

In 2022, according to the Reshoring Initiative, reshoring plus foreign-direct investment resulted in 354,000 new manufacturing jobs, up 53% from 2021.

The Biden Administration projects the Infrastructure Act will create around 550,000 new manufacturing jobs.

Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute anticipate the shortfall in U.S. manufacturing workers during the next decade to be higher than earlier estimates of 2 million unfilled jobs from 2015 to 2025. Their report states that the Fourth Industrial Revolution “is poised to transform work at an unprecedented pace” and create “a mismatch between available workers and the skills necessary for open jobs.”

How qualified will the entry level workers for the factory floor be to handle many of the digital solutions that are needed to create the Smart Factory of the future? Perhaps we have the cart before the horse, and it is time to take a hard look at who the entry level workers are in terms of their strengths and weaknesses.

In the development of No Child Left Behind, policymakers focused on the solutions they wanted rather than the strengths and weaknesses of the students. Manufacturing is also focused on the solutions they want (the digital revolution) and not on the applicants they will get. When you look at the NAEP scores for high school 12th graders, there seems to be a huge disconnect between the skills needed in manufacturing today and the skills and knowledge of people coming out of high school.

The jobs are there, but it may take more than just technical training to prepare young people for careers in manufacturing.

Beyond the apprentice-type training needed for skilled jobs, manufacturing should also be taking a hard look at the reading, math and science skills (or lack thereof) of entry level workers. Hiring entry-level workers may require investing in upskilling, remedial courses and the re-education of entry level applicants to give them the skills and understanding they didn’t get in high school.

The road to Industry 4.0 is problematic unless something can be done to alleviate high school skills problem for 75% of students.

Michael Collins is the author of a new book, “Dismantling the American Dream: How Multinational Corporations Undermine American Prosperity.” He can be reached at mpcmgt.net.