After Months of Silence, Comet Lab Calls Home

PARIS—Europe's comet probe Philae may soon resume work after seven months in hibernation, delving deeper for existential secrets thought to lie hidden under the surface of its frozen host, controllers said Monday.

Mission officials are overjoyed the rugged little lab has survived deep, dark cold perched on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko since November 15.

And now it may now get a grandstand view of 67P's dramatic transformation as it hurtles towards a close encounter with the sun, they hope.

On Saturday, Philae called home for the first time since running out of power on November 15, and made contact again for about four minutes on Sunday.

The washing-machine-sized lander's battery is being recharged as the comet streaks toward our star at about 19 miles per second, with mothership Rosetta in orbit.

Sunday's connection was "pretty short and pretty faint," European Space Agency (ESA) senior science advisor Mark McCaughrean told AFP, but "we got some data down."

"The last (contact) actually was very short but... it was real time," added Alvaro Gimenez, ESA's director of science and robotic exploration.

"We see that the system is improving, it is getting the right temperature, and it's going to work," he told journalists at the Paris Air Show.

Once stable communications are established, teams hope to relay commands to resume experiments with 10 onboard instruments.

"This will take a few days, one week, less than one week, to start doing the science," said Gimenez. "We are now really excited."

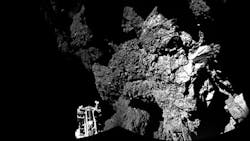

The probe's touchdown on November 12 was a bumpy one--Philae bounced several times on the craggy surface before landing in a shady spot, deprived of sunlight to replenish its battery.

It had enough onboard power to send home data from about 60 hours of experiments before going into standby mode.

The mishap has yielded an unexpected boon: if Philae had functioned as intended, powered by sunlight at the start of its mission, it would likely have overheated and died by about March.

"We wouldn't be seeing the comet at its most active phase, which we will now," said McCaughrean.

By Monday, the lander was receiving three hours of sunlight per comet day, according to the German Aerospace Center (DLR).

Comets are deemed to be frozen balls of dust, ice and gas left over from the Solar System's formation some 4.6 billion years ago.

Researchers are eager to probe the wake of gas and ice particles 67P is blasting out, the material on its surface and, crucially, what's inside.

Where do we come from?

Their findings may answer a fundamental question.

Did comets, slamming into a proto-Earth, bring water and amino acids--the building blocks of life?

"We want to actually drill into the surface and see what it's like, what the material is like locked into the ice there," McCaughrean told AFP.

"That's the material left over from the birth of the Solar System, which is the real game here."

One of Philae's star instruments is a drill designed to penetrate to a depth of 25 centimetres (9.8 inches). But after landing, the probe perched at a 45-degree angle against a rocky wall and its instrument "drilled" uselessly into space.

"What we hope to look at now is whether we can rotate the body of Philae... and maybe put the drill into a place where we might be able to then actually go into the surface," said McCaughrean.

The teams also hope to launch an experiment searching for carbon molecules, and continue measurements of 67P's internal structure with radio beams bounced between Philae and its mothership.

Philippe Gaudon, Rosetta project head for the French CNES space agency, said simple tests will start first, "which do not consume a lot of energy", like testing the comet's temperature.

"Then will follow the cameras, and much later drilling."

67P will reach perihelion, its closest point to the Sun on August 13, before looping back into deep space.

Scientists are curious to see if it will survive this close encounter--the narrow "neck" of the rubber-duck-shaped comet has a crack in it.

"The surface is completely covered in dust, and if it was to break down the neck there, then we'd see the material directly on the inside," said McCaughrean.

Copyright Agence France-Presse, 2015

About the Author

Agence France-Presse

Copyright Agence France-Presse, 2002-2025. AFP text, photos, graphics and logos shall not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten for broadcast or publication or redistributed directly or indirectly in any medium. AFP shall not be held liable for any delays, inaccuracies, errors or omissions in any AFP content, or for any actions taken in consequence.