People Management Practices and Profitability in Manufacturing

People are billed as companies' most important asset so routinely that we should be surprised they don't all sleep nights in a corporate vault. Yet, in the hard-nosed, bottom-line discipline of managing organizations, the "soft skills" of people management practices are more often an afterthought than a core strategy linked to superior business performance. And while manufacturers' workforce management practices have moved far beyond the personnel office of decades past -- with its origins in managing masses of low skilled workers in a pre-technological age -- many have a long way to go to engage their people and connect these practices to shareholder value. Talent management for many manufacturers could be characterized as a less than ideal blend of new aspirations and old tactics.

| In May 2009, Deloitte, The Manufacturing Institute, and Oracle jointly conducted a national survey of manufacturing organizations to assess the current performance of companies with respect to people management practices, as well as the future importance of these practices. They were asked to identify the top drivers of their future business success, and to comment on talent shortages experienced today and expected within the next two to three years. Profile of Survey Respondents The survey was conducted via the Web, on an anonymous basis, to which 779 individuals responded. The distribution of respondents was as follows: Primary industry sector: Aerospace & Defense -- 6% Automotive -- 6% Consumer Products -- 9% Energy & Resources -- 3% Industrial Products -- 43% Life Sciences & Medical Devices -- 2% All other -- 31% Methodology We sorted the respondents based on their self-reported earnings before interest, tax and depreciation (EBITDA) and identified the top quartile and bottom quartile companies based on EBITDA. We tested for statistically significant difference in the current performance of each of the people management practices between the bottom and top quartile EBITDA firms. We performed a similar analysis for gauging the importance of the people management practices. |

The road to useful conclusions is often paved with hard data. In our research, we found that answers to some of these questions lay in excellence in specific aspects of people management practices. The data suggest that certain practices help some manufacturers outshine the rest. These companies have developed clear talent management strategies that align consistently with their overall corporate strategy and complement their culture and values in ways that point to improved results.

What Sets Them Apart

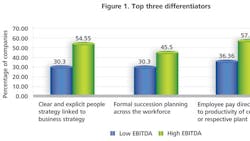

Recognizing that larger companies have the scale and resources to develop more comprehensive talent management strategies, we focused our research on the largest 142 companies from our survey. The most profitable large companies share three practice areas that differentiate them from the least profitable companies:

- Defining a clear and explicit people strategy that is linked to the business strategy;

- Performing formal succession planning across the workforce; and

- Linking employee pay directly with productivity of the company or to the respective manufacturing plant

Developing a People Strategy that Supports Business Strategy

Any business strategy ultimately depends on people for its successful execution. Acquisitions, mergers, downsizing, off-shoring, partnering, you name it -- people are central. But the people strategy needed to drive and support a high-end, intensive-customer-experience retail company is very different from that needed for a mass-merchandise, low-cost discount retailer, and vastly different from a customized, specialty engineering and manufacturing aerospace and defense firm. Yet relatively few employers have developed an explicit and documented people strategy tailored to their business goals.

Of the largest companies that participated in the survey, 55% of those with top quartile profitability rated themselves "high" in linking people management strategy to business strategy, while only 30% of bottom quartile profitability companies reported similar performance (figure 1). Among all the survey respondents (regardless of size), the figures stand at 44% for the most profitable companies and 36% among the least profitable.

In many organizations, the HR function does not participate in the strategy development process nor does it have complete visibility into corporate or business unit strategies. As a result, corporate strategy and people strategy are developed independently and people management practices may be misaligned with corporate objectives. For example, an industrial products company may develop a strategy to increase its service revenues by twenty percent over the next three years, but if it fails to measure and improve service orientation among employees, it will likely fail to achieve that objective and may also find its employees de-motivated.

The most profitable companies, the data would suggest, align people practices to corporate strategy. According to GE's vice president of human resources for Australia and New Zealand, Sam Sheppard, rather than being an administrative function, HR initiatives, actions and priorities must be aligned with the business plan.

"There is no point being an add-on function, a reactive partner for the business," Sheppard said. "It's very easy sometimes to get sidetracked on what we would like to be doing, but if we can't translate that into a bottom-line impact for the business, then that lessens our value to the organization."

After struggling with lack of focus and losses in the billions in the early 1990s, Sears Holdings Corp. likewise overhauled its strategy implementation process. A senior management team incorporated the full range of performance drivers into the process. Then, they articulated a new vision: For Sears to be a compelling place for investors, the company must first become a compelling place to shop; and for it to be a compelling place to shop, it must become a compelling place to work.

Sears validated the vision with hard data, designing a system to objectively measure each of the three "compellings." The team extended this approach by developing a series of related competencies that employees were required to hone and identified behavioral objectives for each of the "compellings" at several levels through the organization. These competencies then became the foundation on which the firm built its job design, recruitment, selection, performance management, compensation and promotion criteria. The company also instituted the Sears University to develop these competencies.

Recognizing that it is important for HR managers to be familiar with the broader aspects of the business, Coca-Cola rotates top-performing line managers into HR positions for two or three years to build the business skills of its HR professionals and thus make the function more credible to the business units. At Procter & Gamble, an HR manager is expected to work in a plant or work alongside a key-account executive to learn more about the business and its needs.

Formal Succession Planning Across the Workforce

Well-defined succession planning takes a long-term view of talent within the organization. It develops talent to step into key roles on a timeline consistent with anticipated - and unanticipated - vacancies. Lack of rigorous succession planning can hit companies hard. It takes them longer to replace critical talent and often at a higher cost from external sources.

Among the largest companies in our dataset, 45% of companies with top quartile profitability exhibit high ratings in formal succession planning while only 30% of bottom quartile companies performed similarly. Looking at all respondents (regardless of size), 36% of the highly profitable companies rate their current capabilities in formal succession planning as "high," while only 20% of the less profitable companies rate themselves similarly. A majority have yet to establish an effective succession planning process.

Many organizations struggle when it comes to grooming successors for key positions. Succession planning, as traditionally conceived and executed, is narrowly focused on identifying employees who are ready for promotion, usually only at senior executive levels. A long-term talent management strategy should look beyond the C-suite to prioritize succession of all critical positions based on specific organizational needs and strategic direction.

According to Johnson & Johnson, the ability to groom future leaders is crucial to removing a potentially significant constraint to its future growth. Each year J&J's CEO launches the talent review process with a letter addressed to executive vice presidents reinforcing the importance of leadership development and also highlighting a new area of focus for that year to emphasize succession management priorities. J&J uses bottom-up succession reviews to discover and grow talent first at the operating company level, then at the group level and finally at the corporate level. As a result, talent review now takes place in every aspect of J&J's business planning with continuous examination of capabilities and development needs of executives in the context of larger organizational needs.

Colgate-Palmolive also developed an innovative way to ensure that all levels of management make succession planning a priority. It instituted a program that mandates that all senior managers must retain 90 percent of their staff who have been designated as "high potential," or risk losing part of their compensation.

Linking Employee Pay to Productivity

Among the largest companies in our survey, 58% with top quartile profitability ranked high in linking employee pay to productivity, while only 36% of bottom quartile companies performed similarly. Considering all respondents (regardless of size), 55% of highly profitable companies rate their current capabilities in linking employee pay to productivity as "high" compared to only 41% of the less profitable companies.

Organizations are increasingly placing emphasis on rewards management programs and performance-based pay. Deloitte's 2010 Top Five Total Rewards Survey reports that 66% of respondents plan to make changes in the design of compensation plans, with particular emphasis on performance-based pay, and performance management tracking and administration.

Siemens successfully transformed its employee compensation system as part of its value-based management program. Before launching the program, performance-related pay was a small proportion of total compensation, even for the most senior executives. After the launch of the program, approximately 60% of the remuneration of the top 500 executives became performance-related. Siemens based this on current share price and investor expectations of the improvement in economic value added over the next year.

At Nucor Steel, employees involved directly in manufacturing are paid weekly bonuses based on how much their work groups -- each ranging from 20 to 40 workers -- produce. Typically, these bonuses are calculated on anticipated production time or tonnage produced, depending upon the type of facility. The formulae for determining the bonuses are non-discretionary, based upon established production goals. This plan creates pressure for each individual to perform well and, in some facilities, is tied to attendance and tardiness standards.

Nucor department managers earn annual incentive bonuses based primarily on the return on assets of their facility. Senior officers receive no profit sharing, pension or discretionary bonuses. Instead, a significant part of each senior officer's compensation is based on Nucor's return on stockholder's equity, above certain minimum earnings. If Nucor does well, the officer's compensation is well above average, as much as several times base salary. If Nucor does poorly, the officer's compensation is only base salary and, therefore, significantly below the average pay for this type of responsibility.

Manufacturers are facing unprecedented long-term business and talent challenges, a situation which offers tremendous opportunities for individual companies to separate themselves from the pack. Our research suggests that certain people management practices can help some manufacturers achieve superior profitability. Through talent strategies that are innovative, forward-looking and closely aligned with the company's overall strategy, a manufacturing organization can address its short-term challenges while positioning itself for long-term success.

Richard Kleinert is a principal in Deloitte Consulting LLP's Human Capital practice. Emily Stover DeRocco is president of The Manufacturing Institute. Atanu Chaudhuri is a manager in Deloitte Research, Deloitte Support Services India Pvt. Ltd. Robert Maciejewski is a senior manager in Deloitte Consulting LLP's Human Capital practice.