Five Pricing Myths You Should Avoid at All Cost

When executives in industrial markets think about trying to get a price premium for their products, they often raise the white flag before even stepping onto the battlefield. Five beliefs, in particular, have become ingrained to the point that they seem immovable.

While companies dedicate ample resources to continually reduce costs or sell greater volumes, they rarely invest to the same extent in their pricing capabilities. As a result, they leave money on the table.

Fortunately, the experiences of leading companies in markets ranging from precision instruments to chemicals show that industrial manufacturers and suppliers usually have far more pricing flexibility than they realize. These companies have managed to break through the five self-limiting beliefs described below through deliberate efforts to redesign pricing approaches and sales practices.

Many companies pigeonhole themselves as price takers, believing higher prices or a tougher stance on pricing will cause customers to defect, especially when a product or key input trades on public markets as a raw commodity. In most cases, price takers overlook a range of other factors that customers care about and that justify a price premium.

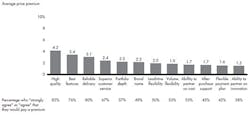

A recent Bain survey of almost 300 purchasing executives for bulk raw materials such as metals, chemicals, agricultural commodities and paper goods asked executives about the role of price in their purchases relative to other elements of the overall proposition. Price is rarely the most important decision criterion, the survey showed. In fact, as shown in the chart, customers will pay a 4.2% premium for higher quality and a 3.1% premium for more reliable product delivery. Moreover, 88% of customers would pay at least 2.5% more for a product—and some customers much more—to avoid switching suppliers.

Customers Would Pay A Premium for These FeaturesA supplier can use surveys and past buying behavior to segment its customer base according to differences in key purchasing criteria, which decision makers are involved and how many bids typically are requested. It can then quantify how differences in products and services create differences in each segment’s value. Where there are meaningful opportunities, these differences can be baked into a company’s pricing structure.

Many business customers only want to pay for actual results that a product delivers, rather than for potential results. In addition, more customers want to shift capital expenses to operating expenses, reducing the need for large, up-front investments. They’re demanding new price meters – jet engines priced per mile or per hour flown, rather than per engine, or copiers priced per printed page, rather than per machine. This model allows them to pay for the value they receive, not for capacity they never use.

The key, then, is to tailor the product’s pricing model so it directly addresses a wider set of customers’ needs and priorities. Once the enabling infrastructure is in place to properly implement a new price meter, major changes can be executed swiftly, without customer hand-holding, if a company has sufficient market power and authority.

Google did this with its App Engine platform for software developers. Many of the major mobile phone carriers moved quickly when they shifted from unlimited data pricing to models with tiered usage-based pricing. Each was determined to make its pricing reflect the real costs and risks it was incurring by moving to a new business model or by accommodating power users that had been getting a subsidized ride.

In many industries, sales incentives emphasize bookings, not profit margin. That motivates sales representatives to give away too much on price simply to close the deal, without considering the economic value of the final deal. To complicate matters, individual reps often negotiate different discounts for the same product, and the companies have no standardized procedures to assess the appropriateness of a proposed discount.

Help salespeople help themselves. Equip the salesforce with business intelligence to make smarter pricing decisions, and install a clear, fast process for decisions that need approval. The salesforce should be armed with statistically based guidance on how to price deals, factoring in deal characteristics that emerge as bids are developed. Commissions, bonuses and other forms of compensation should be redesigned to promote discounting that benefits the company’s long-term economics, not short-term volume gains.

One asset leasing company, for instance, was plagued by an “every deal is unique” mentality which depended on the market, the time of year, asset characteristics and the nature of the customer. This variability made it difficult for management to influence pricing decisions, and an assessment showed that pricing leakage was common. By building simple deal-pricing tools and establishing rules based on an escalating system of approvals, the company was able to bring order to the pricing of most standard deals. That elevated the truly unique, important deals to senior executives so they could make the final decision based on a broader strategic perspective.

When discount programs and promotions proliferate, suppliers lose control. Various discounts—volume, minimum level of spending, new account, product and geography-specific, and front-end and back-end—might each make sense in isolation. In aggregate, though, they sometimes allow partners and customers to qualify for a price that’s below cost.

To counteract this complexity, it pays to refresh on a regular basis the portfolio of discounts, focusing on a small number of important incentives with meaningful benefits. The portfolio ideally has:

* A finite number of major incentives for channel partners

* A simple, clear set of programs and promotions that are aligned to incentives. Remove obsolete discounts and focus on those with the highest return on investment.

* Performance-related discounts balancing revenue growth and margins – like giving a discount to a channel partner that hunts new customers who meet the right parameters.

In most B2B settings, customers often conduct an initial supplier screen that factors list price into the mix. If a supplier’s pricing strategy consists of high list prices and high discounts, and that runs counter to the norm for a particular market, the company will get knocked out of consideration early.

Developing a pricing playbook will ensure that prices are set based on the product’s economic value to customers and its life stage. Alongside that playbook should be a process for regularly checking foreign exchange and competitors’ price moves, so that list prices stay locally competitive.

For companies that make acquisitions or have a range of products with different pricing dynamics, it’s valuable to create a menu of pricing options that acquired companies can choose from to hit the right list and net price points. The menu should provide enough flexibility to allow products to be competitive, but should also limit options to minimize complexity.

Pricing is important enough to warrant a true owner who can provide a companywide perspective on pricing trade-offs, even if the final decision rests with product and market leads. The practical challenges demand an executive who can assemble the pieces strewn throughout the organization into a coherent whole, and engage the active collaboration of functions outside of product, sales and marketing. That’s what it takes to break free from the five shackles and regain the pricing flexibility required for profitable growth.

Clearing the Roadblocks to Better B2B Pricing

Stephen Mewborn is a Chicago-based partner and Justin Murphy is a San Francisco-based partner of Bain & Company.