Automakers' Choices Around ICE Vehicles Are Everything in the Short-Term

IndustryWeek's elite panel of regular contributors.

Automotive manufacturers and suppliers are currently making decisions on vehicle programs that will be launched in an era of more stringent emission regulations. Suppliers should expect minimal disruption in the gasoline-powered space.

The automotive vehicle business has always been a high-risk and high-investment sector. The risk gets compounded by program development time, typically four to five years depending on the complexity of program changes.

Government regulations pile on more risk and complexity. The proposed fuel-economy and emission standards are now key parameters when deciding on potential portfolio changes.

However, the new regulations will not supersede placing customer needs and wants at the top of the decision pyramid. Most mainstream vehicle buyers are not ready to take the leap to battery-electric vehicles, and the demand ramp-up will be much slower than the initial vision statements assumed. That is reality.

A Critical Moment

Given development times, manufacturers need to make decisions this year and next on major program redesigns they will launch from 2027 to 2029, the first few years of the proposed regulations.

However, the biggest incremental risk will not come from decisions in battery-electric vehicle development. Manufacturers have already indicated a willingness to take that path over the long-term. New BEV programs expected over the next five years in the North American market will exceed 100 entries. Everybody is racing to get these vehicles into production and take some of Tesla’s customers.

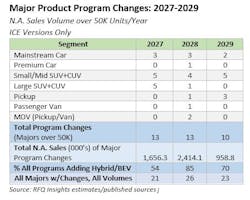

The real risk comes from not updating the high-volume internal-combustion-engine (ICE) programs summarized on the chart below. During the next 16 months, manufacturers will need to decide what to do with the 33 ICE programs slated for majors during 2027-2029.

The sport utility and pickup products deliver today’s profits. Ironically, it is these ICE programs that could determine the value of a company’s stock—not the perceived future performance of BEV programs.

Additionally, passenger cars represent strategic entries that capture customers looking for a better price and value. These customers exist across all countries in the North and Central American regions. Asian brands have not forgotten this market segment.

Here are my estimates for program changes for 2027-29 (using RFQ Insights' proprietary formula with verified data):

The North American sales volume for these vehicles represent 5-13% of industry sales. Importantly, all provide significant component volume for automotive suppliers; a considerable number sell over 200,000 units a year.

Given the importance of these programs to OEMs and suppliers, we anticipate 2027-2029 ICE majors will be approved, with a few twists:

- The “majors” may not be as significant as in years past. Suppliers need to compare changes with proposed volumes. Gasoline powertrains are also expected to improve.

- Some programs will be delayed, with OEMs trying to get 6-7 years out of today’s program. Suppliers should anticipate minor interior and exterior changes.

- A considerable number of programs will have hybrid or BEV versions added as powertrain alternatives to ICE trims.

However, don’t look for these ICE programs to dropped and replaced exclusively with BEV versions (except for four that we are aware of). They can’t. The current battery technology and charging infrastructure will not allow it. Sure, battery cost reductions and more fast-charging stations are coming down the road. But realistically, CEOs need to make 2027-2029 decisions today, knowing that customers will remain dubious about BEV performance for some time. Their vision must also deliver purchase price parity through cost reduction rather than profit-margin reduction (easier said than done).

Manufacturers need a realistic plan from the EPA

The conflict between OEMs and the government over proposed emission standards will intensify beyond the old Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) debates. Car and Driver, in a recent issue covering electric vehicles, said “the EV space changes fast.” Could not agree more. Every aspect of battery development, motor quality and lightweighting is being explored and revised at a rapid pace. Setting standards that force drastic portfolio changes too soon may hurt North American manufacturers in their most profitable market.

General Motors recently added more weight to this argument. Their calculation of a $100 billion in industry penalties if EPA rules are adopted starting in 2027 must certainly include more ICE vehicles that customers want, but the current administration does not.

There is logic in keeping high-volume ICE/hybrid versions in play—and every manufacturer knows it. If manufacturers are looking to ultimately replace their entire portfolio with BEV technology, then they need emission-regulation flexibility. Giving customers more choice until BEVs have been proven is a more practical mainstream solution.

The 100 BEV entries planned over the next five years will drive the required economies of scale, supply chain efficiencies and infrastructure changes. How about the proposed standards starting in 2030? That will provide three more years of BEV sales data in North America. Hopefully, it will demonstrate that a single vehicle—other than Tesla’s 3 and Y—can sell more than 50,000 units a year (at a profit).

Time to wind down the BEV hype machine. The strategy of letting customers decide the portfolio mix may butt heads with whiz kids in the government. Yet it may also lead to more tranquil quarterly investor calls, and a better long-term solution.

Warren Browne is president of RFQ Insights and is adjunct professor of economics and trade at Lawrence Technological University. Browne retired from General Motors in 2009 after 39 years of service. From 1991 to 2009, he held senior executive positions at GM.

***To comment on this article, please scroll down past story recommendations to "Voice Your Opinion."