The Constant Battle Between Sales and Manufacturing: Demand vs. Capacity

“How many units can we reliably supply our customer?” asks the V.P. of sales. “And don’t make us look like fools by telling me a number that will never be consistently met!”

“I will tell you that number,” said the V.P. of manufacturing, “just as soon as you look in your crystal ball and give me a forecast that predicts how many units you all will sell over the next 12 months!”

Does this conversation sound familiar? It is the constant tension that usually puts up big, thick silo walls between sales and manufacturing, the two organizations that have an impact on either side of the demand/capacity equation. If the V.P. of sales were to ask the question above, would manufacturing be able to give a straight answer? Would the response begin with all of the reasons why an answer is not possible (model mix, seasonality, unpredictable downtime and quality issues, etc.)? Or, maybe the answer is a theoretical maximum output. (“One day, last decade, we produced X number of units, so that is my answer.”) This response will cause great frustration if the sales folks thought “X” was a real number and started planning to try and create that much demand. The more likely answer will probably be something with the word “average” in the mix (“We average making Y units per day/week/month.”). Of course, the problem with driving demand to an average is that roughly 50% of the time the output will be too low to meet the expectations.

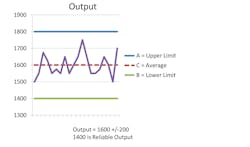

The better answer would be a range based on a process behavior chart of actual output: "We can reliably produce somewhere between A and B with an average of C where A and B are the upper and lower limits." If the sales V.P. pushed hard enough (“How many units can we reliably supply and let’s assume our jobs are on the line?”), then the only number that can be used is the lower limit (B) -- which in some cases may be close to zero.

This tension between sales and manufacturing can cause great damage to the customer experience and eventually drive the company out of business. How would things be different if this were not the case? What would happen if there were no silos and sales and manufacturing worked as a team to try and balance capacity with demand? The benefits could be enormous.

To best illustrate what this relationship might look like, I will share one of my past experiences. For those of you who are accustomed to my writing style, you know I like to use a narrative with characters based on actual events and people. This protects the identities of the organizations and leaders who were involved. The example below will include two characters from my new book,The Façade of Excellence: Defining a New Normal of Leadership. Jim Brown is a leader who is trying to do the right thing by engaging the employees in order to build trust, collaboration and empowerment. Frank Smith is based on a leader who gets ahead by manipulating data and using fear to motivate the workers creating a “façade of excellence.”

The day for Jim Brown began like every other day. He woke up, got ready for work and drove to the local manufacturing plant in his old Ford pickup truck. He arrived just in time to stand at the main entrance and greet many of the workers as they began their shift. Even though Jim was the director of quality and manufacturing engineering, he knew most of the employees by name and routinely told them to be sure and let him know if he could do anything to help.

Jim noticed a piece of paper on his computer keyboard when he walked into his cubicle. “Notice!” it said in an official- looking font. “You and your direct reports are expected to attend an emergency meeting with the V.P.s of sales and manufacturing today at 11:00 a.m. in the main conference room. Do not be late!”

“I wonder what this is about?” thought Jim. “I am not sure I have even met the V.P. of sales before. Something big must be about to happen.”

Jim showed up with all of his direct reports promptly at 11. “We have a serious situation that will need to be dealt with if we want to keep our largest customer from leaving and taking 40% of our business with them,” began the V.P. of sales. “They are planning to expand their stores by offering over 200 new franchises in all of the territories they do not currently cover. In order to fill these stores, two months from now, they plan to double their current orders with the expectation that all products will be delivered on time.”

“At least they are giving us some notice instead of springing this on us,” said the V.P. of manufacturing. “The good news is that since we started our lean journey 18 months ago, we have seen our output numbers go from 1,300 units plus or minus 1,000 per day to 1,800 units plus or minus 100 per day. (Yes, this is data from the actual experience when we put our output on a statistical chart… since we had a huge backlog, the daily schedule was fairly consistent) When the new orders come in, the expected demand will increase to approximately 2,000. We have done a great job of building trust and collaboration with our employees, so I want to do everything possible to avoid mandatory overtime in order to bridge this gap.”

Jim Brown raised his hand and said, “I suggest that we redirect all of our employee teams to aggressively identify and break bottlenecks in order to raise the output. We will also need to work with our suppliers to make sure they have enough capacity to keep us healthy with raw materials and parts. In addition, we can build on our aggressive preventative maintenance plan to make sure our equipment runs reliably. I believe with the progress we have made using the lean and Six Sigma tools, our employees are in a great position to help. We need to let them know what is about to hit us in two months.”

“I agree,” said the V.P. of manufacturing. “I will set up an all-employee meeting and ask everyone for their help. Also, let’s involve all of the team leaders when we create a plan to get us through these next four months.”

“One other thing,” said Jim as he moved to the front of the room. His boss moved aside and gave him the floor. Jim looked into the audience and said, “In this room, we have representatives from several different functions including sales. When all of these additional orders hit in a couple of months, there will be a strong temptation to begin pointing fingers when the wheels begin to wobble. I want each one of us to make a commitment right here and now to not let this happen. We are a team and we will either win as a team or feel the wrath of an angry customer as a team.” The audience of sales reps, supervisors, engineers, schedulers, and purchasing folks stood up and began to applaud to show their commitment.

Across town, Frank Smith, the director of operations for a different company that supplied product to this same customer, was in the process of discussing the latest increase in the poor quality numbers with his quality manager when the phone rang. “Hello boss. The sales guys are telling you what?! Our largest customer wants to double their orders in a couple of months? What a bunch of baloney! Those sales guys are always padding their numbers. As soon as I ramp up production, they will most certainly pull the rug out and I will be stuck with a bunch of useless inventory. Alright,” Frank said with a tone of defeat, “If I must do something, I guess we can start filling our warehouses with finished goods and hope they order what we have in stock. I will get right on this boss.”

Frank slammed the phone down. “The things I am forced to do by a bunch of do nothing salespeople who wouldn’t last a day in my shoes!”

“What if we pick the wrong stuff to make?” asked Frank’s director of quality, who had been listening in on the conversation. “Don’t we run the risk of using up all of the materials in our supply chain and ending up with a bunch of finished goods we don’t really need?”

“Don’t worry,” said Frank. “I already know the exact people in the sales group and supply chain I can throw under the bus if that happens. One way or another, I plan to come out of this unscathed and, who knows, if we get lucky and pick the right stuff to make, maybe I can position myself to accept my next promotion.”

Down the hall, at about that same moment in time, the sales manager said, “Frank Smith is going to do what?! Build a bunch of stuff and hope? That is taking a huge gamble with our biggest customer. Those people in manufacturing don’t have a clue and are going to run us out of business!”

Four months later, Jim Brown was sitting with a group of employees eating lunch. “I can’t believe we did it,” said one of the team leaders. “Our output last month was just over 2,100, with only a variation of plus and minus 10 units. I never thought that was even remotely possible.”

“Yeah,” said another leader. “And that was with a minimum of overtime, and we did not add a single new employee. The crazy thing is, I did not see a single person working any harder than they were before. Breaking the bottlenecks and getting rid of waste freed up a ton of unused capacity.”

“The sales team has been great to work with through this effort,” said Jim. “We have been holding quick update meetings every day, and that helped us greatly with the scheduling process.”

“I have to admit,” said one of the engineers sitting at the table, “there were several times, especially when it looked like we might miss some orders, I was tempted to start looking for people to blame. But I kept going back to that meeting and realized we must all work together if we had any hope to pull this off. I hope this team effort, especially with the sales folks, continues.”

The actual organization that went through this difficult time used the lessons learned to continue to drive their improvement efforts. A year after these events, they had achieved output of 2,300 plus or minus one unit per day. It did not matter if it was the beginning of the month, the day before a holiday or the beginning of summer vacation. Through the lean and Six Sigma principles of visual management systems, employee engagement, quality improvement, level loading scheduling systems, etc., the workers were able to achieve a stable, predictable system of manufacturing. This led to market share growth (with happier customers) and a significant improvement in profit margin. Why did margins improve? The answer to this question is the payoff of the investment to achieve excellence.

The Battle between Demand and Capacity

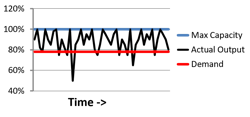

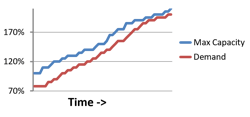

In the chart below, if the line at 78% represents the current level of demand, at first glance it might appear that there is not a problem. However, there are two significant concerns with this profile.

First, the output is erratic to the point of being unpredictable. In fact, the output on several days is below the demand, which could result in late shipments. The manufacturing leaders may not see this as a problem since they can make up for the deficits on the “good days.” Second, there is little incentive to sell more products since it already seems that the wheels are always one step from falling off. Note: This gets even more complex if there has been no attempt to smooth the demand. Imagine what would happen if the red line was as jagged as the blue. The hatred between sales and manufacturing would be significant.

Constant communications (weekly sales and operations planning meetings, for example) and a team effort to smooth demand (spot sales, customer incentives, making off-seasons products to balance seasonality, etc.) are essential to not let this happen.

Step 1: Eliminate Chaos and Complexity

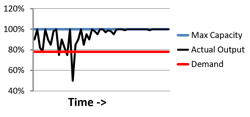

What would happen if manufacturing could smooth the output line by building robust systems?

By making the process more predictable, it becomes easier to see the bottlenecks. This gives the improvement teams an opportunity to figure out ways to increase overall capacity by smashing these constraints.

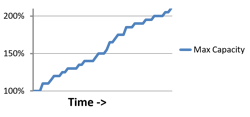

Step 2: Break Bottlenecks to Increase Capacity

Once output increases, manufacturing and sales can work together to sell this additional capacity. Think about the profit margins of these additional sales. Since the costs of labor, overhead and facilities have already been absorbed by the existing output, every additional unit has fantastic profit margins. This assumes little to no additions to achieve this new level of output (this is more realistic than one might think when large amounts of waste are removed from the system using the lean principles). If this is the case, the only increase in cost would be the materials and utilities needed to produce these additional units. For example, if the split in costs are 40% labor, 20% overhead, and 40% materials/utilities the profit margins would jump to 60% for each additional unit produced and sold… a huge number.

Step 3: Sell Demand for a Fraction of the Cost

One of Dr. Deming’s 14 principles to running an organization is: “Break down barriers between departments: People in research, design, sales and production must work as a team…”

Implementing lean, Six Sigma and collaborative teamwork takes real dedication at every level in the organization. This can be a significant investment (time, training, coaching, etc.). However, the return on this investment will be enormous. For example, in one organization I had the privilege to work with, after three years on their lean journey, manufacturing had gotten to the point of sharing real-time demand of their bottleneck operations with their sales teams (who had also gone through all of the same lean training and participated on improvement teams). This allowed for dynamic pricing based on how much capacity was currently available. This system resulted in higher customer satisfaction, an increase in sales, and profits went up significantly.

Those organizations that have embedded the lean concepts and philosophies into their culture know the enormous potential this creates. However, lean is not just for manufacturing. All parts of the company must be involved in order to balance demand with capacity and break down the silos. This journey can only happen with stable, predictable systems, and a truce is reached in the battle between sales and manufacturing.

John Dyer is an author, coach and trainer with 35 years of experience in the field of improving processes. His recently published book The Façade of Excellence: Defining a New Normal of Leadership examines the four leadership styles required to move an organization’s culture to one of trust, collaboration and teamwork. Dyer started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company. He has had the opportunity to study with such leaders in the continuous improvement field as Dr. W. Edwards Deming, Brian Joiner and Stephen Covey. Dyer has an electrical engineering degree from Tennessee Technological University, as well as an international master's of business from Purdue University and the University of Rouen in France. He is a contributing editor for IndustryWeek magazine and a judge in the annual IW Best Plants contest. He can be reached at [email protected], @JohnDyerPI (Twitter), or via his LinkedIn profile.

About the Author

John Dyer

President, JD&A – Process Innovation Co.

John Dyer is president of JD&A – Process Innovation Co. and has 32 years of experience in the field of improving processes. He started his career with General Electric and then worked for Ingersoll-Rand before starting his own consulting company.

John is the author of The Façade of Excellence: Defining a New Normal of Leadership, published by Productivity Press. He is a frequent speaker on topics of leadership, continuous improvement, teamwork and culture change, both within and outside the manufacturing industry.

John is a contributing editor for IndustryWeek, and frequently helps judge the annual IndustryWeek Best Plants Awards competition. He also has presented sessions at the annual IW conference.

John has an electrical engineering degree from Tennessee Tech University, as well as an international master's of business from Purdue University and the University of Rouen in France.

He can be reached by telephone at (704) 658-0049 and by email at [email protected]. View his LinkedIn profile here.