7 Steps for Leading Lean with Respect for People

With Lean Thinking, Jim Womack and Dan Jones ushered a true (and rare) revolution in management thinking: To deliver a superior order of performance, leaders should lead from the workplace, the “gemba” to use the lean term (it means real place, real products, real people) and not from the boardroom.

Like the air we breathe, the established paradigm of 20th century leadership is so ubiquitous that it is hard for anyone to question it. A leader’s job is to come up with strategies for what to do and how to do it, and managers execute organizational processes so that employees do what they’re told. “Gemba” leadership turns this idea on its head, asserting that superior results will be achieved if leaders spend all their time encouraging small-step continuous improvement at the workplace (“kaizen”) and then they’ll learn about their strategies and processes from working with their people rather than thinking in their stead.

A seductive idea, but rather hard to swallow -- as any leader who’s taken his or her first steps with lean management will bear witness. A leader serious about learning lean will first find a sensei and commit to “gemba walks.” During these tours of the shop floor (or office workspace), the sensei will make a big production of showing apparently minor things out of place, such as a pile of files on someone’s desk or a crate in a corridor, and then will demand (yes! Demand!) 1) better visual control (whatever that means) and 2) problem solving, sometimes in the form of improvement workshops to discover the causes of these problems.

To the traditional leader, no matter how genuine their interest in lean, this is totally bewildering:

- Why should these details matter?

- Why should they be concerned about them – and not frontline management?

- What do we expect to gain from fixing that level of “problem”?

- How can any of this somehow translate in superior company-level performance?

The paradigm gap and the very different management assumptions made in lean thinking, make these questions hard to respond to satisfactorily, other than saying that leaders who’ve done it in earnest have had the results (after 20 years of documented lean evidence, no one much disputes that).

First, watch out for the No. 1 trap. As is well known in lean circles, the leader is likely to latch on to one specific tool and pull it back to their understanding of project management. For instance, the leader will fall in love with, say value-stream mapping and use it as a mainstream management tool: They’ll hire a lean specialist to map processes, organize workshops to improve processes with nominal employee participation (we’re involving people, aren’t we?), establish performance improvement targets and, well, manage the “transformation.”

Small Performance Improvements Backslide to Average

This, usually, delivers low-hanging fruit results, but reality exists and reality resists: Performance will not improve that much before returning to average.

For instance, let’s consider the business of making specialized stage machines for the entertainment business. Responses to customers are too slow, customer requirements poorly understood, engineering is always late, production makes many mistakes, purchasing takes forever to procure special components, and logistics can’t ever deliver to customers on time -- no surprises here, same old, same old.

A superficial understanding of lean will then lead to a value-stream mapping workshop that will show that having production working independently from engineering with a big buffer of design files ready for assembly in the middle doesn’t make much sense. The process can evidently be leaned by creating “value-streams” by which some production cells will work with a few engineers in a “mini-business” configuration, which will radically accelerate the flow of work and bootstrap the company’s performance. The project can be scoped with objectives, managed by change agents and supported by management champions.

The theory is perfectly sound, but unless we’re very, very lucky, this is unlikely to deliver the desired results. The existing process is, in fact, the reflection of peoples’ actual skill levels: sales skills to capture real customer requirements, engineers skills to design performance, not just CAD drawings, production skills to produce quality on time, logistics skills to procure rapidly and so on. Implementing the new process will simply confuse operations further, and unwittingly favor some files versus others according to skill levels in the “value stream” teams.

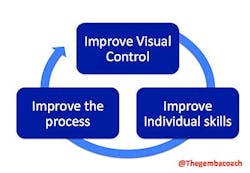

The lean approach would be very different. Before changing anything in the process we would need to commit to continuous improvement of:

- Visual control of each area – logistics, production, engineering, procurement

- Individual skills

- Cooperation across functions

Visual control is about teaching the employees themselves how to structure their work environment in order to see at one glance whether the situation is OK or NOK.

In our example, this could be drawing out on the floor areas for truck preparation before the truck arrives. In engineering this might be setting up a kanban board to see how engineers take projects one at a time rather than have files accumulate on desks.

Visual control tricks need to be learned, and require some discipline. At first all and sunder will resist it because highlighting the difference between what we planned and what really happens shows up problems everywhere, all day long. This makes everyone uncomfortable: Employees don’t like to be caught out by their bosses and managers hate not having an immediate response to solve all problems.

Invariably, detailed problems will surface skills gaps – people know how to do some things better than others. The core issue of performance is, not surprisingly, one of competence. Jobs are late because of rework. Things are misplaced because of confusion. Processes break down because of poor communication.

As people take ownership of visual control and start clarifying their interfaces, many issues will arise. If leaders succeed in getting people to solve problems one by one, then they will learn (and leaders will learn about what hurdles the organization throws at staff to stop them from doing good job). We will find, for example, that engineers send drawings to production without detailing how the equipment should be assembled, and so on.

As each department learns to do its job better as well as better interface with each other within the existing process, opportunities for structural process improvement will appear. In our case, creating small cells with a few engineers and a few operators to accelerate the flow of specially made products will become feasible because people will understand what is expected of them and will find ways to make it work.

Change will then become easier to implement and far more sustainable – and then we can continue to improve the degree of visual control, of problem-based training and look for the next opportunity of improvement – this is the lean way: Frontline management takes responsibility for visual control, employee training and ultimately process improvement.

A Model of Gemba Competences

Furthermore, many managers will have experienced firsthand that “management by walking about” at the workplace without visual controls in place is more disruptive than helpful and has not much in common with a lean “gemba walk.”

Leaders and managers might want to acquire lean practices, but they simply don’t know how – they might have the motivation but they lack the skills.

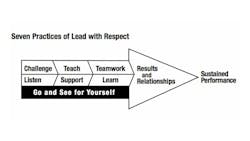

Lead With Respect is an attempt at detailing those gemba management skills and to give them a broader context in terms of company performance. On the advice of John Shook, Lean Enterprise Institute CEO, we drew up a model of “gemba competences” for how to lead with respect:

1. Go and see for yourself: to see the facts firsthand rather than read reports. This is a sampling approach rather than an overview attitude. No more “in a nutshell” briefings. By looking at specific cases at the customers’ or at the workplace, leaders can better understand context and values. Furthermore, the key to sustainable continuous improvement is to get people to agree on the problem before they start arguing about solutions – go and see is a foundational political as well as technical skill.

2. Challenge: the energy that fuels the continuous improvement engine. Challenging means demanding that visual control should always more be more precise and better owned by operators, that problem solving be more rigorous and seeking root causes, that process improvement deliver more results and more customer oriented. Challenge also means explaining how step-by-step improvements link up with the company’s overall business challenges and objectives to orient the improvement efforts and make everyone feel they contribute to a larger collective project.

3. Listen: listening means looking out, at the workplace, for the specific obstacles that get in the way of employees doing their job well, whether thankless tasks, poorly performing equipment or suppliers, asking them to do things beyond their competence level or personal difficulties. Every second of a person’s life is precious, and listening means very specifically hearing how and why we waste people’s time – whilst not reacting (and often killing the messenger), pooh-poohing the difficulty or coming up with a pithy solution.

4. Teaching: teaching problem-solving skills and improvement skills. In a knowledge society, employees are often far more expert than their managers at their jobs – they know what to do. Yet, we need to establish a professional conversation about work. The trick is to focus on problem solving and improvement efforts, which enable us to delve quickly into technical issues even though we don’t always master the ins and outs (on the other hand, managers do have the larger context).

5. Support: Whenever an employee has an initiative, the likely answer from middle-management is likely to be “can’t do that.” Supporting improvement means exactly that – learning to say “go ahead” to people when they come up with new, untested ideas, especially when it goes against the grain of organizational habits. The skill lies in learning to listen and discuss well enough to avoid having to say no to hare-brained schemes and encourage instead very small risk-free steps (risk for a senior manager and for a workplace employees looks very different).

6. Teamwork: The quality of the problem solving is directly linked to the quality of the teamwork. Teamwork means being able to solve problems across functional boundaries – it’s the key to successful process improvement. In order to establish the right grounds for process improvement, leaders must constantly develop teamwork by teaching individuals to work with their colleagues across functional silos (and, yes, this sometimes involves banging heads together before they agree to do so).

7. Learn: As you gain in experience with gemba walks, you discover that as employees learn, you learn. Leaders have the big picture, but as we all know the map is not the territory and the word “cat” doesn’t scratch. By involving oneself deeply in problem solving and employee initiatives, leaders discover that their mental maps are not always framed in the right, fit-to-fact manner. As people on the ground learn, you learn, which is probably the most profound discovery (and message) of lean leadership.

These seven skills are practices, not vague intentions (“listen more” is hard to disagree with but not helpful). These are practices leaders learn by spending hours on the gemba observing and discussing visual management and the problems it reveals.

In our experience, without mastering these foundational behavioral skills, even with their heart in the right place, leaders fumble their presence at the gemba and, consequently, feel disappointed by the bottom-line results they get from their lean efforts. Lead With Respect aims to make explicit these key skills to help managers leverage their lean efforts.

Michael Ballé, PhD, is a lean management practitioner, business writer and author. His most recent book, co-authored with Freddy Ballé, is Lead With Respect: A Novel of Lean Practice, published by the Lean Enterprise Institute. As managing partner of ESG Consultants, Paris, he helps companies and executives adopt lean systems and behaviors. Ballé is associate researcher at Télécom ParisTech's Projet Lean Enterprise and co-founder of the French Lean Institute.