Are You Really Different? Lean Flow for Skilled Repair Work

How many times have we heard these comments from clients on why lean will not work?

- “We are different. Every job is unique.”

- “We cannot expect teamwork from skilled trades. Their work is too specialized.”

- “We must keep our people busy at all times. That’s why inventory is so important.”

Let me tell you a story about how we transformed a sophisticated aircraft repair facility, made up of many skilled tradesmen, into an effective lean team.

The Challenge

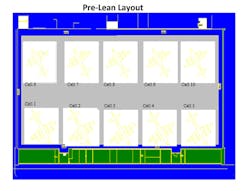

This is an illustration of the challenge we faced at a military aircraft repair facility in Florida:

The facility repaired and performed scheduled maintenance on large aircraft. One aircraft was located in each of the 10 cells shown. Each aircraft was disassembled, inspected for damage, repaired, reassembled, tested and released to the fleet. This process took a lot of time—about 247 days per aircraft. There was no flow, as “every job was unique.”

The Pre-Lean Process

The process design shown in the illustration posed a number of problems/opportunities. Much of the metal repair work was done on the wings. The wings, which were also the fuel tanks, were disassembled for inspection and repair. Fixtures were not available to support the aircraft with disassembled wings. Instead, once repair work began, the wings were on jacks and the aircraft was immobile for many days/months.

Imagine also the challenge of moving an aircraft out of the hangar. If, for example, all work was completed on an aircraft in Cell #3, it took much wasted waiting time to create an exit path by moving immobile aircraft out of the way for its release.

Of course, as soon as an aircraft was removed from a spot, another aircraft was moved in to take its place. That way, if we ran out of parts for one aircraft, we could easily move to another and “keep our skilled trades busy.”

To add to our timing delay, many completed aircraft failed fuel tank/wing leak tests and had to be reprocessed. This created another challenge—finding an available spot for the repair work (along with the associated movement of immobile aircraft).

The Lean Process (for a “unique” “skilled-trade” craftsman process)

This repair depot had no experience with lean and in fact little experience with any serious improvement process. We determined that the best way to shake them up to understand the challenges and huge opportunities of lean were through five-day rapid improvement workshops. We got teams of trades workers and supervisors together to understand the current situation, define targets for improvement, redesign the workplace, and make many of the changes during the week when we had them captive. Then we would follow up to refine the changes so that they became the new standard process. We focused on reducing waste…walking for parts, walking for tools and materials. We also focused on standards: 5S, standardized work, visual controls, parts storage, etc. This improved repair time, but, we wanted more.

The major transformation occurred when we stopped thinking about each aircraft as an individual, unique job and started thinking about process flow:

We discussed ways we could attack common problems such as:

- Efficient and timely removal of completed aircraft from the hangar with minimal waiting time.

- Timely repair of aircraft that failed final testing.

- Getting the right tools and materials to the right stage of disassembly, repair, reassembly.

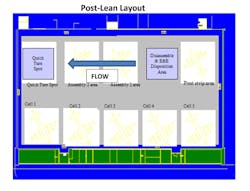

Our breakthrough came when we started thinking about flow to meet customer demand. It seems obvious now, but it took a long time for our team to first accept flow and second figure out how to create a future state layout that supported flow. Instead of thinking of 10 separate and unique cells or “mini job shops,” we decided that if we were going to flow, we needed a flow lane.

In an ideal world, we would have created a moving line. We did not have the investment funding required to support this. Instead, we did the next best thing. We divided the hanger in half. Five cells were used for metal repair and rework. These were the cells with immobile aircraft on jacks. The space previously designated as Cells #6 - #10 was now identified as our flow lane. The planes were already on wheels by this point so they could be rolled between cells. By dividing the stages of work into defined steps, like an assembly line, we now could establish standard work for each process step, bring the right tools and materials at the right time to that process step, establish metrics including timing that were visually posted, and engage the team in thinking about ideas for improvement. They even agreed to share tools instead of each repair specialist carting around their own large toolkit—it was cheaper and the tools could all be centrally maintained.

This resolved many delay problems such as entry and access of aircraft and location of aircraft requiring minor repairs after inspection. Of course, standardized work reduced reprocessing time significantly. As a result, we reduced lead time from 247 days to 200 days.

In the end this “unique” situation was unique, but the approach for improvement was quite generic. With a focus on the customer and flow, standard work, 5S, and most importantly engaging the value-added worker in improvement, we had yet another case of generic lean principles applied creatively to a new situation.

For additional information, see Chapter 5 of The Toyota Way Fieldbook by Jeffrey K. Liker and David Meier. The book contains additional details on the transformation.

_________________________________________

Join the Liker Leadership Online Community and access our webinars, courses, and consulting services. Liker Leadership Institute (LLI) offers an innovative way to learn the secrets of lean leadership through an online education model that is itself lean, and extends that lean education far beyond the course materials. Learn more about LLI's green belt and yellow belt courses in “The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership” and “Principles of Lean Thinking” at the IndustryWeek Store.

About the Author

Ed Kemmerling

Senior Lean Transformation Expert

Ed Kemmerling has over 25 years of manufacturing leadership experience, and over 15 years of lean transformation experience. He was responsible for the monitoring and alignment of Ford Production System (FPS) Lean Six Sigma Manufacturing implementation at more than 40 Ford facilities worldwide.

He has led and implemented Lean Six Sigma System transformation activities since 1996, and is presently associated with Dr. Jeffrey Liker as a Senior Lean Transformation Expert, Coach, Mentor and Consultant.

Ed has been very successful in driving change and results at a number of facilities. At Caterpillar’s Aurora Facility, he developed a process that engaged the entire workforce in the Caterpillar Production System. He mentored Black Belts and Master Black Belts at the location. The result was a 35% improvement in less than one year.