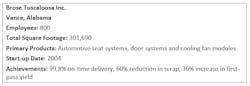

2021 IW Best Plants Winner: Brose Tuscaloosa's Drive for Innovation

When I first entered the Brose Tuscaloosa Inc. plant—tucked in the shadow of a massive Mercedes-Benz facility in Vance, Alabama— I sincerely believed I was going to find a technology story.

This wouldn’t have been too far off, really.

Over the past few years, this automotive seat, door and cooling fan system maker has invested heavily in new robotic cells, state-of-the-art welding systems, automated line testing equipment, semi-autonomous forktrucks, and whole host of other very cool, very tech-driven productivity-boosters.

On paper at least, the success the plant has seen over the past few years—36% first-pass yield improvement, 60% reduction in scrap, 99.8% on-time delivery, and so on—seem directly attributable to these investments.

And even in the plant—despite the steady march of metal and mechanical components being carted and welded, painted and coated, assembled and tested through their streamlined production arc—the newly expanded facility carries that clean, well-lighted, automated hum of digital transformation.

Put this together and Brose Tuscaloosa’s IW Best Plants win really seems like a technology story. It should be a technology story. But it’s not. It’s a people story.

The People Story

“I don’t know everyone’s name yet, but I know all their nicknames,” Jim Barbaretta —general manager of both the Brose Tuscaloosa and New Boston plants—tells me midway through our tour of the Tuscaloosa facility. I don’t think he was exaggerating.

Barbaretta grew up in this plant—he has worked his way up through Brose North America for the past 22 years and came into the Tuscaloosa facility as employee number 24. He knows every inch of the place, every cell, every machine, and (it honestly seems) every employee. We could hardly move 10 feet without him breaking away from the group to chat and joke with another worker. A one-man morale machine, practically.

This management approach seems purely genuine—based on my observation, Barbaretta is friends with everyone here because he is legitimately friendly and legitimately cares about them.

But there is a practical benefit to this charisma, too.

“This area is short on resources,” Barbaretta says. “There’s a constant battle to bring in employees and stabilize fluctuation.” To a large extent, this is an issue generally out of Barbaretta’s direct control. Brose Tuscaloosa is just two quick turns from the city-sized Mercedes plant, which, as you would expect, is a Brose customer. But the small town is filled with other suppliers as well. Throw in a new Amazon warehouse down the road and you’re left with an extremely dense concentration of manufacturing and labor opportunities for a town with a population of just about 1,700.

“This is a booming area,” Barbaretta explains. “There are more openings here than unemployment claims right now—so even if you put everybody on unemployment back to work, you’re still short in the labor market. That’s a hard challenge.” It really is tough. Brose can’t invent workers, of course. But it can create working conditions that more workers will want to be part of. And that is exactly what the team has done.

Over the past few years, Brose Tuscaloosa has all but eliminated its temp worker program, opting instead on direct permanent hires. It has increased its starting wage by $1 per hour and its shift premiums from 45 cents to $1. It has built an impressive cafeteria on campus offering fresh-cooked, healthy food (which is subsidized for employees—they pay $5 and the company picks up the other $7 or $8). And it has partnered with a local community college to launch a mechatronics apprenticeship program to train its own future skilled workforce.

And that’s just the beginning—Brose Tuscaloosa also practices a “management build” program every month across all three shifts, requiring each manager (Barbaretta included) to jump on the line to be trained by operators. This is an important practice for teambuilding, of course, but also for improvement.

“We get to find out the things they’ve learned to work around that we don’t want them to work around,” Barbaretta explains.

If there is an ergonomic issue, managers feel the ache of it; if there is too much walking, it hits the managers’ feet, too.

But perhaps the most effective practice here is the cross-training. Above every single workstation in the plant hangs a tiny placard indicating the “difficulty” of its task.

These signs indicate which certifications qualify the 100% cross trained-workforce to jump in if needed—and leads to a constant race to develop more skills and collect more certifications to operate higher- rated cells.

This is especially important today, given the incredible disruptions happening across the automotive space. When semiconductor stocks dry up and automakers stop production, competitors with less diverse product portfolios or a less flexible workforce are forced to idle or lay off workers. But Brose Tuscaloosa can simply shift them to other lines and other operations without missing a check.

You combine all these tactics with culture-building leaders like Barbaretta, and you’re left with a world-class, people-focused organization that seems positioned to take on any challenge.

“All of this makes a difference,” says Patrick Neely, director of production at Brose Tuscaloosa. “It makes a difference where people want to work.”

The Technology Story

The people side of the story is significant to the plant’s success. But let’s not forget how this story started—technology investments so significant that they almost mask the people factor.

Some of these stand out just as particularly effective, quality-oriented systems.

Like the acoustics evaluation system that “breaks in” seat assemblies and measures vibration (rather than sound) emitted by the seats under pressure during their full-travel operation—right on the line, on 100% of the assemblies.

Or there’s the pilot program for a self-correcting welding system that could one day eliminate the need for destructive testing.

Or the new barcoding system, etched straight onto the rail, which provides full traceability for every part from stamping to delivery.

But what stood out to me wasn’t those massive, objectively impressive installations.

Rather, it was a series of smaller automation cells stuck right on the line, composed of simple, off-the-shelf-type components.

This comes from a very innovative approach to production planning, which usually focuses on peak volume years—which doesn’t occur until about the third year of production, Neely explains.

“What we did was not just focus on peaks years, but on being profitable from the first year to the last,” he says. “We needed a concept that make us a little more flexible.” This flexibility came in the form of “smart automation”—robotic cells built and installed on the line to pick up some of this variable workload.

“In peak years, maybe a line will need 10 operators and in nonpeak years, you just need eight. But if we implement a robot that could handle a certain portion of the handling, for instance, then you can already start with that eight-person scenario,” Neely explains. “When peak comes, because you already have the robotic solution there, you don’t need to add the other two—so we’re as profitable as we can be right from the onset.” But that’s just the start— the mechatronics apprenticeship program Brose developed with Lawson State Community College has created a new talent pipeline that frees the plant from making the often-heavy investments required of such robotic cells.

“Now we have the ability to build our own equipment if we want,” Neely says. “That definitely gives us a leg up.” It means Brose Tuscaloosa—using a few off-the shelf robots—can design its own automation cells on the fly, eliminating inefficiencies across the life of a line, supplementing trained workers, and greatly reducing demand volatility on an already strained labor force.

It achieves exactly what every world-class manufacturer only dreams of, using just a little ingenuity and the wisdom to invest in a smart long-term strategy.

The Innovation Story

If we put these two sides of the Brose Tuscaloosa story together—the people and the technology—I believe our decision to include it in the 2021 class of IW Best Plants winners becomes pretty clear.

In an age of technology for technology’s sake, when workers are still too often seen as replaceable commodities, this plant gets it right. It took impossible resource constraints and talent shortages and turned them into a drive for innovation—constantly testing, constantly experimenting, developing new concepts and new models and new approaches that serve both its customers and its workers better and more efficiently than the competition.

Brose Tuscaloosa achieved excellence, it achieved world-class results, it achieved a spot in the IW Best Plants winner’s circle not because of robots, not because of technology alone, but because it also invested in its employees and gave them the tools and the experience they need to succeed. In this sense, it’s not a technology story at all; it a story of genuine empathy and people-first continuous improvement.

"Brose Tuscaloosa is a great company to work for," says Arpit Desai, lean industrial engineer at Brose. "Since I have been at Brose, Jim [Barbaretta] and Patrick [Neely] have been very supportive and have always encouraged me to [to pursue] new ideas and innovation."

About the Author

Travis Hessman

Content Director

Travis Hessman is the editor-in-chief and senior content director for IndustryWeek and New Equipment Digest. He began his career as an intern at IndustryWeek in 2001 and later served as IW's technology and innovation editor. Today, he combines his experience as an educator, a writer, and a journalist to help address some of the most significant challenges in the manufacturing industry, with a particular focus on leadership, training, and the technologies of smart manufacturing.