Five Questions OEMs Should Ask About Vertical Integrated Outsourcing

I recently visited one of the largest manufacturing companies in China to investigate their capabilities related to the design, development and manufacture of LED lighting products. Upon stepping onto their massive production floor in China, I immediately observed (as I’m certain was the plan) that the entire factory was lit with branded LED products manufactured by the company.

Throughout the course of my visit, I learned of their incredible depth of vertical integration capabilities specifically focused on the emerging LED lighting market. This brand name Chinese manufacturer, utilizing its own internal vertical capabilities, basically sources raw material in the form of fiberglass, aluminum, silicon and plastic resin, and produces the vast majority of the components and subsystems required to manufacture a broad range of finished LED lighting products. Although very different technology, process and geography, the occasional industrial history buff in me could not help but liken this plant back to Ford’s River Rouge operation circa 1928.

Much of the modern origins of vertical integration of supply pioneered by Henry Ford in the early 1900s was driven, in part, by economic and practical necessity. The tremendous pace of technological advancement and industrialization often required firms to develop their own internal sources of component supply as a well-developed supply base for many new parts and new technologies had not yet had time to develop. With the unsophisticated production planning and communications technologies available, external transaction costs were high. The basic economic benefits of vertically integrating seemed compelling and large-scale vertical integration became the normal way of organizing manufacturing operations for most product companies for the next 70 years.

Move Towards Specialization and De-integration

Even before the rapid rise of outsourced manufacturing in the early 1990s, most of the world’s OEMs had started to shift away from vertical integration. As the rate of technological advancement continued to accelerate, most OEMs began embracing a new calculus for evaluating future production decisions that started to favor differing levels of movement away from full vertical integration. Factors influencing the broad move away from captive vertical integration in the late 1970s included:

- Excessive investment in fixed capital to support broad, vertically integrated manufacturing limited their ability to invest in R&D.

- Rapid changes in manufacturing technologies drove increasingly complex decisions for OEMs around captive manufacturing process selection and the impact on the firms’ future products.

- Recognition that vertical integration without geographic co-location provided very limited benefits over external sourcing.

- The complexities of managing a very large organization to support vertical integration often overwhelmed other savings or resulted in sub-standard components or subassemblies.

In other words, whereas increased scale often provides certain economies to various operating costs, the increasing scope of an organization has the potential to provide meaningful diseconomies associated with excessive complexity and lack of organizational focus. As increasing product variety and functionality drove more fixed costs and managerial complexities into OEMs’ captive vertically integrated manufacturing, companies re-evaluated what manufacturing competencies were truly core to their competiveness.

Seeking to reduce their diseconomies of scope, OEMs slowly dismantled their massive internal supply operations and sought to purchase more materials from specialized suppliers that were more narrowly focused around specific technologies. Although managing these “best of breed” suppliers required internal overhead and drove external transaction costs, their narrow specialization allowed them to produce superior products for the money – without the need for massive fixed capital investments or massive organizational overhead for the OEM.

Outsourced Vertical Integration

As is often the case, a well-reasoned concept from the past has been given a new lease on life, reincarnated as a key component of an evolved, modernized supply chain solution. Today a fair number of outsourced manufacturing service providers have embraced vertical integration as a key aspect of their competitive positioning, and many more tier 2 suppliers manufacturing service providers are now starting to move in that direction.

Unlike the massive vertically integrated OEMs of yesteryear seeking to increase responsiveness and reduce transaction costs, most manufacturing service providers that pursue vertical integration are primarily motivated by the potential to capture the higher profit margins that accrue to various components in the supply chain. As a result, the industry has developed a somewhat reconstituted supply chain model: Outsourced vertical integration - the internalization of various key supply elements by outsourced manufacturing service providers.

5 Questions OEMs Should Ask

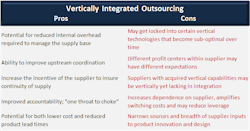

Obviously there are pros and cons to vertically integrated outsourcing and the model works well for some products and less well for others. We see a lot of OEMs today wrestling with the question of whether or not vertically integrated outsourced manufacturing is the right model for them. The following five questions can help OEMs better understand the model and determine whether it is something that they should seriously consider.

1. What is the complexity, and level of maturity of the manufacturing processes needed to manufacture the key components or subsystems I’m considering having my vertically integrated manufacturing services provider build?

One of the most significant arguments regarding vertical integration, whether outsourced or captive, is the capital investment required to provide a wide range of parts and services. Many vertically integrated suppliers cannot afford to have the latest and greatest process technologies across their entire portfolio, and often will seek to sell the customer on their existing process technologies rather than what the customer really needs.

2. What is the relative cost of shipping, handling, and stocking of the parts?

Vertical integration, especially if coupled with co-location, can provide significant cost benefits in the form of reduced material related overhead. Parts where shipping and handling costs between vendors is significant can be good candidates for vertical integration at your contract manufacturer.

3. Is the demand for the product continuous with some underlying predictability, or is demand highly variable and uncertain?

Components with sporadic demand, high unpredictability of demand, or very low volumes generally do not realize much benefit from vertical integration. Finding a highly responsive, best-of-breed component supplier is a safer bet for these types of components.

4. How stable is the component design?

Stable designs lend themselves to vertical integration in the supply base more so than a design that has high potential for revisions and ongoing modifications. Again, a well-positioned best of breed supplier is generally more capable of responding quickly to design changes – especially when they impact a major process.

5. Is the supplier I’m considering really vertically integrated, or do they simply own a bunch of independently run operations that produce some components?

The underlying economics of vertical integration are driven by reduced external transaction costs and all of the various activities and costs that go into these transactions. For vertical integration to deliver on its economic promise, transaction costs within a vertically integrated supplier (communication, coordination, material movements, inspections, etc.) must be significantly lower than similar external, open market transaction costs. Vertical integration requires far more than a supplier buying a company with some upstream capability and changing the sign out front. The key economic advantages of vertical integration are based primarily on the integration and less so on the vertical.

About the Author

Ron Keith

Chief Executive Officer

Ron Keith brings more than 24 years of operations experience to Riverwood Solutions including engineering, manufacturing and executive management positions at Westinghouse, Wavetek, Rockwell, Alcatel and Flextronics International. Ron has a reputation as an innovator, team builder, creative problem solver and strategic thinker who delivers straight talk and strong results to Riverwood's clients. He has run international EMS operations with annual sales in excess of $1.4B and has managed manufacturing, product development, and program management personnel in numerous countries.

Ron has advised more than four dozen companies on their manufacturing operations, supply chain, and outsourcing strategy including more than a dozen Global Fortune 500 companies. He has previously consulted for four of the top 10 EMS (Electronic Manufacturing Services) companies and has advised hedge funds, private equity funds and strategic investors on a number manufacturing services related investments. Ron has published more than 30 articles on various manufacturing, technology and business related topics including strategy, operations, quality management, technology trends, and supply chain management.

Prior to founding Oreamnos Partners and Riverwood Solutions, Ron served as Vice President and General Manager at Flextronics International, where he started and ran several divisions in both the EMS and ODM (Original Design Manufacturer) spaces during his more than eight year tenure. He worked with, and ran manufacturing operations for, a number of leading OEMs at Flextronics including Cisco, Motorola, JDS Uniphase, Nortel. W.L. Gore, Kyocera and others.

Ron has undergraduate degrees in both Electronic Engineering and Manufacturing. He received an MA in International Management and an MBA in Operations Research from the University of Texas at Dallas, where he also completed the majority of coursework towards a Ph.D. in Organization, Strategy & International Management (OSIM).