As the U.S.’s biggest manufacturing exporter, Boeing (IW500/9) is uniquely vulnerable to radical shifts in trade policy. The incoming Trump administration has promised major trade policy changes, implying or promising renegotiation or cancellation of key multilateral agreements and the enactment of trade barriers. All of this represents risk, not just for Boeing, but for the entire U.S. commercial aerospace industry.

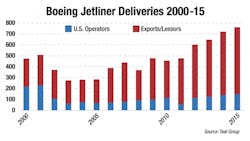

Consider Boeing’s heavy dependence on free trade and open borders: about 5,500 of the 7,522 jets delivered by Boeing in 2000-15 were exported.

More important, as indicated by our chart, Boeing’s market is trending very heavily toward exports. In 2000, U.S. operators took 46% of all Boeing jetliner output; in 2015 they took just 20%. Deliveries to U.S. airlines in that period fell by a 2.4% compound annual growth rate (CAGR). Deliveries to non-U.S. operators and lessors grew by a 6% CAGR.

On top of the international market’s importance, all large civil aerospace primes have created elaborate global supply chain networks, which depend on the relatively frictionless transit of parts between countries.

There is no clear way to know what impact the new president will have on the industry; all we can do is look at possibilities. A recent New York Times column outlines three possible trade policy approaches for Trump.

The first possible course is that world trade agreements and institutions remain intact, but the U.S. takes a more assertive stance within them. This might create a few relatively modest barriers, but would not be a major threat. In fact, Boeing might benefit if the U.S. gets more aggressive about the U.S.-EU Boeing/Airbus trade complaint.

The second is that trade agreements and institutions remain intact, but the president uses his authority to enact much more aggressive tariffs and other barriers. This would primarily target China. Trump threatened a 45% tariff on all Chinese imports, which would immediately produce a trade war. An obvious target would be jetliners, with orders shifted from Boeing to Airbus. This is the greatest risk for Boeing. In 2015, the company delivered 145 jets to China, or 19% of jetliner output, their most important export market.

The third possibility would be the end of the post-World War II trade order. Before and after the election, Trump vowed to withdraw the U.S. from the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership. He also promised to renegotiate or terminate NAFTA. The Trump administration will consider ignoring World Trade Organization (WTO) rulings, which would jeopardize that institution—and make the U.S.-EU jetliner trade case irrelevant.

There is no way of telling how badly jetliner markets would be affected by this third possible course. Since the remarkable growth of air travel and jetliner deliveries has been closely linked with world trade, it is safe to say that if trade slows, so will long-term jetliner demand. Growing protectionism is already taking its toll on world trade; in September the WTO cut its trade-growth forecast for the year to just 1.7%, the slowest rate since the 2008 financial crisis.