How the Decline of Unions and Collective Bargaining Hurts Manufacturing and Our Economy

In the last 20 years, corporate efforts to lower labor costs have been extremely successful, resulting in record profits and executive bonuses. Big corporations have outsourced jobs to low-labor-cost countries, created two-tier pay systems, and implemented automation and other labor cost reduction strategies. Among the most successful is their effort to weaken or eliminate unions.

But I wonder if their success may come back to haunt them -- and the country -- in the future.

For example, IBM Corp. (IW500/11) conducts a survey of 1,500 CEOs around the world each year, and in 2010 concluded that “more than rigor, management, discipline, integrity, or vision -– successfully navigating an increasingly complex world will require creativity.” But the question is, how will corporations recruit and motivate these creative people -- and retain them -- unless they are willing to give them bargaining power and change the current business paradigm of "cost reduction first."

These same corporations are also faced with the fact that they need highly skilled workers to operate their very automated plants. According to many research reports, manufacturing needs 600,000 highly skilled people today, and this number will continue to grow as the baby boomers retire. Why should highly skilled people pursue a career in manufacturing when they view it as a declining industry whose companies do not hesitate to reduce wages, outsource jobs and close plants?

In my April article, Why America Has a Shortage of Skilled Workers, I shared some information from an earlier report from the National Employment Law Project, Manufacturing Low Pay: Declining Wages in the Jobs That Built the Middle Class. If you doubt that manufacturing wages are falling, here's a chart from the report:

Source: National Employment Law Project, Manufacturing Low Pay: Declining Wages in the Jobs that Built America's Middle Class: Calculations by the authors. (Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment Statistics, data for NAICS SECTOR 31-33.

These same corporations support STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education initiatives and are very critical of our current educational systems. Why should a young person invest in a STEM education in an industry that has lost six million workers and 82,000 factories since 2000? New workers want to work in an industry where there is job security, wages based on skills attained, good benefits, and the job is presented as a long-term career.

... manufacturing executives are not in good position to recruit the people they need based on what has happened in manufacturing in the last several decades."

Meanwhile, a survey about public perception of U.S. manufacturing, conducted by Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute, found the following:

While 84% of respondents rank job security and stability as very important or important job selection criteria, 75% strongly agree or agree with the statement, "manufacturing jobs are the first to be moved to other countries" and 41% strongly agree or agree with the statement, "U.S. manufacturing jobs are stable and provide job security relative to other industries."

Meanwhile, another survey question found that 66% of respondents strongly agree or agree that worries about job security and stability are reasons for not encouraging a child to pursue a career in manufacturing. (Job security and stability tied for third with ability to build job skills in job selection criteria; good benefits was first at 87%; rewarding work was second, at 85%.)

These corporations already are in a position where they must compete for the well educated people, and then motivate them to stay with the company. But manufacturing executives are not in good position to recruit the people they need based on what has happened in manufacturing in the last several decades.

As for the country, the U.S. is a consumer economy, driven by consumer spending. If workers do not have money to spend, the outlook is not good for U.S. economic growth.

A Brief History of Unions

Working people spent the better part of the 19th and 20th centuries trying to gain the right to some kind of collective bargaining. It was a long struggle against corporate owners and managers to get a decent wage and a 40-hour workweek.

Up until the Great Depression, management had the upper hand and firepower, and many workers paid with their lives during the struggle. But in 1936, things began to change. Congress passed the Wagner Act, also known as the National Labor Relations Act, which gave unions greater ability to organize and collectively bargain. The Wagner act also established the National Labor Relations Board to handle disputes and wage agreements.

By 1950, one-third of all workers in all private industries were in unions. Wages and benefits grew for union and non-union workers alike, as both shared in the prosperity of the post-war economy.

From 1947 to 1973, real wages for all workers rose by 75%, according to the journalist and progressive columnist Harold Meyerson. However, from 1979 through 2006, real wages for non-managerial workers rose by only 4%.

Meyerson also notes that from 1947 to 1972, productivity in the U.S. rose 102%, and the median household income also rose 102%. Had wages continued to grow at this same rate of growth, the median wage today would be more than $70,000, instead of $51,000.

But this period of wage growth was not to last, as big corporations were determined to reduce or eliminate the power of unions.

1947 - The decline of unions actually started in 1947, when Congress passed a large number of changes to the National Labor Relations Act. The new law, the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, shifted the balance of power back toward employers. Slowly but surely new legislation was developed to:

- Outlaw the closed shop, in which a person must be in the union to get a job.

- Allow employees to file decertification petitions.

- Prohibit unions from using secondary boycotts.

- Permit the President to nullify a strike if he thought it was a national emergency.

1977 – Congress debated a new bill, the Common Situs Picketing Bill, which would have legalized secondary strikes in the construction industry — and greatly strengthened unions. When President Gerald Ford vetoed the bill, it was a huge loss for unions.

1978 - In 1978, labor unions decided to make a stand by introducing a bill that would promote union organizing and strengthen the decision-making of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) by increasing penalties to violators. Business organized against the bill and outspent labor by 3 to 1. The bill passed the House but was tabled in the Senate and would never return. This was the beginning of a long period of amendments to labor laws and unions would never recover.

Lobbying Money – By 1980, big corporations began increasing their influence on Congress by pouring money into lobbying and hiring thousands of lobbyists. Two of their primary goals were to weaken or eliminate unions and reduce labor costs. It worked very well. In the last 30 years, they have been very successful at either blocking or weakening any legislation that would help unions or collective bargaining.

1980s and 1990s - Union Busting and Strike Breakers - As unions lost power and members, corporations sensed their weakness and became less willing to accede to their demands for wage and benefit increases. Corporations began hiring strike breakers when unions walked out or were locked out, and then they kept them out after the strike. Unions became hesitant to strike, and the number of strikes decreased every decade. There were 371 strikes in 1970 and only 11 in 2010.

2010 – With President Obama in the White House and the Democrats controlling both houses, labor tried to push legislation that would authorize the NLRB to recognize a union if a majority of workers signed affiliation cards. This process, called card check, was killed in the Senate.

More Money - The major corporate lobbies continued to pour money into the effort to weaken or eliminate unions. They are led the Chamber of Commerce, Business Roundtable, National Association of Manufacturers; by corporate-funded lobbying organizations such as the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), Americans for Tax Reform, the Club for Growth, Americans for Prosperity; and large corporations like Wal-Mart, The Coca Cola Company, FedEx, Amway, Exxon Mobile Corp. to name just a few. In 2014, a small sample of the money spent on lobbying includes the following:

- Chamber of Commerce - $124,080,000

- National Association of Manufacturers - $12,410,000

- Business Roundtable - $14,840,000

The efforts seem to have worked. About eight percent of wage and salary workers are now members of a union, down from 20.1% in 1983, the first year for which comparable union data are available, according to Gallup. Further, there are not many unions left, and the ones that are — the United Steel Workers, the United Auto Workers and the Longshoremen’s Union — are fighting for their existence. They know that American Corporations don’t just want lower wages — they want to eliminate unions.

But is American Support for Unions Recovering?

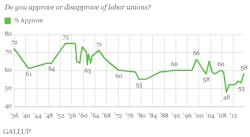

The following chart, from an August 2015 Gallup poll, Americans' Support for Labor Unions Continues to Recover, shows that the public and unions have had, at best, a strained relationship.

In 1936, after the Wagner Act was signed into law, the public supported union workers by as much as 72%. But their support has declined to as low as 48%, possibly the result of the 2008 government bailout of two of the Big Three American auto companies, according to Gallup.

However, the poll, Gallup's annual Work and Education survey, found that nearly six in 10 Americans now approve of unions, up from 48% in 2009.

... nearly six in 10 Americans now approve of unions, up from 48% in 2009."— Gallup Poll Report

Source: Gallup - Americans Support for Labor Unions Continues to Recover, Lydia Saad, Gallup, August 17, 2015

In other findings, Gallup reports that "the percentage of Americans saying they would like labor unions to have more influence in the country has also been rising, and now stands at 37%, up from 25% in 2009. Meanwhile, the percentage wanting unions to have less influence has declined from 42% to 35%, although it remains higher than it was from 1999 through 2008. Instead, fewer today say they want unions' influence to stay the same."

...most positive for the future of unions is the finding that young adults...are the most supportive [of unions] of all age groups."— Gallup Poll Report

Perhaps most interesting and, acccording to Gallup, "most positive for the future of unions is the finding that young adults...are the most supportive of [of unions]all age groups." Two-thirds of 18 to 34 year-olds support unions, and 44% of that age group want unions to have more influence, according to the poll results.

Why Unions Struggle for Approval

It has always been a mystery to me why working people who are not in unions are not more supportive. Even with American support of unions rebounding to where it was six years ago, still nearly half of U.S. citizens do not support unions.

Why? Here are some reasons:

- Right-to-work laws – About half of the states, most recently Wisconsin, Indiana, and Michigan, have adopted right-to-work laws that limit unions from forcing people to join the union. A recent poll showed that 51% of the public supports unions, but 71% are for right to work laws that allow employees to not join unions.

- Corruption – In the 1960s and 70s, when unions were at their strongest, there were corruption trials for Dave Beck, Jimmy Hoffa and other union bosses that defined unions as corrupt and close to criminal elements in society. This “on the waterfront" image is still popular.

- Wages – The public has watched as industry after industry has accepted lower wages and benefits. Regardless of the conditions, unions are blamed because people don’t view them as a worthwhile representative of the average worker. Unions did not prevent the loss of union members or the stagnation of middle class wages -– and they are blamed.

- Lobbying money – As union membership declined so did their ability to contribute lobbying money for legislation. In 1975, about 50% of the senate incumbent’s campaign funds came from labor. By 1985 less than 20% of their campaign funds came from labor and 80% came from big business PACs. This was huge turning point because unions no longer had the money to influence Congress. As a result, unions have lost almost every proposed piece of legislation that would have helped labor in the last 40 years.

- Manufacturing – During and after World War ll, manufacturing was the sector that gave rise to unions and the growth of the middle class. But the decline in the number of U.S. manufacturing workers has reduced their influence. Meanwhile, employment in other sectors of the economy that traditionally don’t have unions — software, the internet, high tech, finance, and retail — have grown faster than manufacturing.

- Unions are weak and getting weaker - With declining membership, have neither the money to fund benefits, such as pension plans for their members, nor to effectively lobby and influence Congress. Many of them are in financial trouble. Because of these and other weaknesses, unions have lost the public relations battle for the hearts and minds of the public.

The Results of Weakening Unions

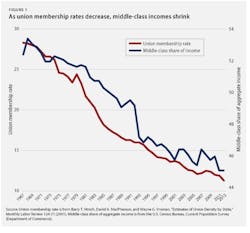

Even though 93% of private industry workers are not in a union, I will make the case that the decline of unions and worker bargaining power has hurt the middle class more than they know. The following graph shows the middle-class share of income almost mirrors the decline of union membership. The graph suggests there is a high correlation between union membership and middle-class income.

There are of course other factors that affected middle-class income, but the decline of unions and their wages was certainly a big factor. The long-term goal of corporations to eliminate or weaken unions was part of a larger goal of reducing labor costs, and they have been very successful.

Inequality – The economist Joseph Stiglitz has asserted that, “strong unions have helped reduce inequality, whereas weaker unions have made it easier for CEOS, sometimes working with market forces that they have helped shape, to increase it. The decline in unionization since World War II in the United States has been associated with a pronounced rise in income and wealth inequality.”

Union jobs typically pay 20% more than non-union jobs, and non-union companies have had to match the wages of union plants for fear of losing employees. This kept the majority of workers’ wages up. With weaker unions, non-union companies can set lower wages. President Obama, speaking at the Business Roundtable said, “although corporate profits are at the highest level in 60 years, stock market is up 150%, wages and incomes still haven’t gone up significantly.”

According to Michael Cembalest, JPMorgan's chief investment officer, reductions in wages and benefits were responsible for about 75% of the increase in corporate profits between 2000 and 2007.

Downwardly Mobile - Many of the workers in the new economy are downwardly mobile, as manufacturing and union jobs are replaced by service jobs. As Harold Myerson points out, “The United States now has the highest percentage of low-wage workers — that is workers who make less than two-thirds of the median wage — of any developed nation. Fully 25% of all American workers make no more than $17,576 a year.”

A Slow-Growing Economy - The uncomfortable fact is that when unions are stronger, the economy as a whole does better. Unions restore demand to our consumer-based economy by raising wages for their members and putting more purchasing power to work.

On the flip side, when labor is weak and capital is unconstrained, corporations hoard, hiring slows, demand drops, and inequality deepens. This is where we are now and we have both record highs in corporate profits and record lows in wages.

Of Unions, Manufacturing, the Middle Class and the Economy

While the corporate effort to weaken or eliminate unions’ collective bargaining power and other strategies to lower labor costs have been effective, I have to ask: To what end?

Though public perception of unions has been negative, it is now on the rise. Have corporations gained so much power over the workforce and held down wages so long, that they risk a backlash?

And even if unions do not make a comeback, has manufacturers’ success in achieving these goals made manufacturing jobs so unappealing, offering a future of stagnant wages and job insecurity, that the skilled-labor shortage persists -- and limits U.S. manufacturers’ ability to grow?

Meanwhile, as the graph on the previous page indicates, relying on the economic forces of labor supply and demand, as well as on “low-cost first” strategies, such as off-shoring, have not improved middle-class income and buying power. The household income of the middle class has declined from 53% of total income in 1968 to 44% in 2012. What effect will continued decline have on our consumer-based economy?

The sad truth is that if workers have no way to bargain for wages, then the slide in income will continue, and perhaps the only answer will be government assistance like expansion of minimum wage and food stamps. Without any collective bargaining power, the American middle class will continue to shrink, concentration of wealth will increase, and corporate control of government will grow.

There is no reason to think that the corporations will suddenly become more sympathetic to working people’s problems, unless they are somehow pressured. So the weakness of unions and labor are every middle-class American’s problem.

If not unions and collective bargaining, government assistance or a change in corporate workforce strategies, then I ask: Where will working Americans get the bargaining power to increase their wages? If 50% of the public do not like unions, then how can working people get any leverage or have any say about what they are paid?

Can some kind of coalition be formed that would have political clout to make demands of corporations. Or will the skilled workforce shortage become so acute that manufacturers and other companies begin to distribute some of the profits to the workforce through higher wages?

But the biggest question is: How can working Americans get enough purchasing power in the future to increase aggregate demand to drive our consumer-based economy’s GDP growth beyond the average of 1.8% since 2000 -- and get back to 3% to 4% GDP growth?