That brings us to EPA's proposed rules that would further tighten restrictions on smog-causing (i.e., ground-level) ozone, lowering allowable levels from 75 ppb to 65 ppb. Judging by EPA data, if the rules go into effect, three-quarters of the country would be unable to meet the new standard. Pursuing these remaining emissions will demand many, many more resources. Which is why, according to another study by NAM and NERA Economic Consulting, it could be the most expensive regulation ever imposed. A classic example of diminishing returns.

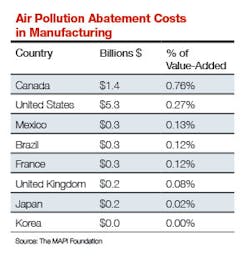

By introducing the most advanced technologies and processes in the world, the American factory sector has made tremendous strides in cleaning up its waste over the past two decades. As manufacturing pollution levels fall, their costs will continue to rise from the current tag of $25 billion per year. Policymakers need to take this, and the overall competitiveness of the sector, into consideration when pursuing their environmental goals.

About the Author

Stephen Gold

President and Chief Executive Officer, Manufacturers Alliance

Stephen Gold is president and CEO of Manufacturers Alliance. Previously, Gold served as senior vice president of operations for the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) where he provided management oversight of the trade association’s 50 business units, member recruitment and retention, international operations, business development, and meeting planning. In addition, he was the staff lead for the Board-level Section Affairs Committee and Strategic Initiatives Committee.

Gold has an extensive background in business-related organizations and has represented U.S. manufacturers for much of his career. Prior to his work at NEMA, Gold spent five years at the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), serving as vice president of allied associations and executive director of the Council of Manufacturing Associations. During his tenure he helped launch NAM’s Campaign for the Future of U.S. Manufacturing and served as executive director of the Coalition for the Future of U.S. Manufacturing.

Before joining NAM, Gold practiced law in Washington, D.C., at the former firm of Collier Shannon Scott, where he specialized in regulatory law, working in the consumer product safety practice group and on energy and environmental issues in the government relations practice group.

Gold has also served as associate director/communications director at the Tax Foundation in Washington and as director of public policy at Citizens for a Sound Economy, a free-market advocacy group. He began his career in Washington as a lobbyist for the Grocery Manufacturers of America and in the 1980s served in the communications department of Chief Justice Warren Burger’s Commission on the Bicentennial of the U.S. Constitution.

Gold holds a Juris Doctor (cum laude) from George Mason University School of Law, a master of arts degree in history from George Washington University, and a bachelor of science degree (magna cum laude) in history from Arizona State University. He is a Certified Association Executive (CAE).