How Not to Lose Your Way: Understanding the 3 Stages of Continuous Improvement

I recently ran a web search for the phrase “Continuous Improvement” just to see what the results look like. As one might expect, the results page contained web sites dedicated to one or more traditional continuous improvement methodologies (Lean, Six Sigma, TQM, etc.) along with links to various books, workshops, seminars and conferences dedicated to the topic.

While there were no big surprises in what I observed, this simple exercise got me thinking about the term and how it’s applied today. Truth be told, the phrase “continuous improvement” (CI) has taken on a life of its own. For some, CI is narrowly defined as the application of a particular methodology or set of tools. For others, it’s broadly applied to any operational changes designed to eliminate waste or otherwise improve performance.

In fact, this phenomenon happens in all walks of life. As an example, my vegetarian wife often has conversations with acquaintances who likewise refer to themselves as “vegetarian” but who actually still eat fish or chicken.

In reality these individuals have only removed certain categories of meat from their diet yet have expanded their personal definition of “vegetarian” to be more inclusive than originally intended. My point is not to infer that they are being insincere or to criticize anyone’s dietary choices but to illustrate the larger point that the definition of some words or phrases gets modified or expanded over time.

Returning to the topic at hand, I think the lack of standardization as to what defines continuous improvement is a real issue because, if a uniform definition no longer exists, then it’s likely that some organizations that truly believe they are engaged in continuous improvement have actually “lost the plot” entirely. They think what they are doing is continuous improvement, but that’s not the case at all.

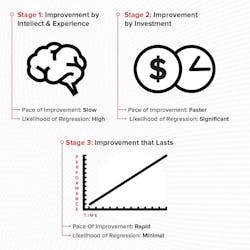

The remainder of the article is designed to contextualize and properly define continuous improvement by looking at it through the prism of a progressive, stage-gated journey as defined in the graphic below:

I recently developed heel pain that was causing me some discomfort each morning and every time I went for a run. After a couple of weeks I started to reflect on what caused it and why it persisted. I remembered that I had purchased a pair of new running shoes just prior to experiencing the heel pain, came to the conclusion that the shoes were the problem, and decided to purchase a different pair.

It’s been a few weeks since I purchased the new shoes and, while I’m still experiencing discomfort, the pain is manageable and my runs haven’t been as uncomfortable as before. So was I right in blaming the shoes for my problem? Hard to tell. What I do know is that I invested in solving a problem without truly knowing that it would address the root cause.

Does Solving a Problem Equal Continuous Improvement?

This anecdote illustrates exactly what happens in many organizations. Specifically, employees regularly make subtle, or not so subtle, adjustments to how they do work based on their intellect and experience and in response to their observations. They might adjust certain equipment set points or process conditions, change the order at which they perform steps in a procedure, rearrange their work station to improve access to certain tools or supplies, or any number of other changes. And in their minds these adjustments represent an improvement. They’re solving a problem, increasing their personal productivity, or making a process better.

But does improving in this way really meet the intended definition for continuous improvement? I think the vast majority of us would say “no” to that question for at least three reasons:

- There is no guarantee that the changes made actually improve the operation because they’re often made based on a set of assumptions which may be inaccurate

- Certain “common sense” improvements may seem sensible but have unintended consequences (e.g., changing the steps in a procedure to be more efficient may increase occupational safety risk, rearranging the work space to make one Operator more productive may make another Operator less productive, etc.)

- The improvements that really do add value are typically not documented anywhere or shared broadly, so no institutional knowledge is generated

To be clear, I’m not saying that we should discourage employees from applying their experience and intellect toward improvement. Far from it. However, we all need to recognize that having knowledgeable, capable employees is necessary, but not sufficient to make continuous improvement possible.

Instead, their intellect and experience needs to be combined with the right methods and tools and channeled through effective business processes so that the best improvement ideas are implemented properly and shared across the organization…which brings us to stage 2.

Stage 2: Improvement by Investment

Stage 2 occurs when the organization recognizes the benefits associated with a more holistic and deliberate approach to managing improvement. Steps taken at this stage typically include:

- Selecting one or more methodologies to serve as the “backbone” of the improvement program

- Putting together a team of CI or functional experts to develop corporate standards, train employees, and put a governance process in place

- Developing an internal brand for the program (e.g., The Acme Inc. Production System, The Acme Inc. Way, Acme Inc. Operational Excellence, etc.) to demonstrate commitment and generate momentum

- Initiating a deployment process to the organization

But to repeat the question asked previously, does stage 2 meet the intended definition for continuous improvement? This is a tougher question to answer because there is no doubt that the organization is showing a commitment to improvement by taking the steps described above. And, in fact, if it’s using a proven methodology and focused on the right opportunities, it should generate significant business value. But let me use a simple analogy to illustrate why I don’t think stage 2 meets the definitional bar for continuous improvement.

I have 2 small boys – 6- and 3-years-old. As you might expect, they are at the stage in life where they need to be closely monitored and managed at all times. I have to constantly remind them to brush their teeth, put their dirty clothes in the hamper, clean up their toys, say “please” and “thank you,” etc.

And because my wife and I are committed to helping them develop the right behaviors, these things do happen (most of the time). However, I also recognize that if we suddenly stopped reminding them to brush/clean up/put toys away, they are not at the stage in their development where they would continue to do these things on their own.

And I think that’s the position in which many companies find themselves. They are making improvement happen, but it’s not operations-driven, self-propelled, truly continuous improvement. Therefore, the program must be given constant attention and regularly infused with new energy.

Despite the fact that tangible gains have been made, the concern that the program will lose momentum and disappear entirely is both palpable and constant.

Stage 3: Improvement that Lasts

Which brings us to stage 3 of the improvement journey; the stage where improvement is truly “continuous.” There are many synonyms for the word continuous -- perpetual, unceasing, unrelenting, etc. – but the synonym that I prefer in this context is the word sustained.

And the reason why I like this word is because there’s an implication that a sustained improvement is one in which there is no possibility for regression…there’s no going back to the way things were. And isn’t that the point…to try to implement a series of improvements that add business value in the short-term and establish a new baseline for future improvements?

This concept of sustainable improvement works on both a micro and macro level.

At a micro level sustainability is achieved when all improvements that truly add value to the business are institutionalized and do not need to be re-instituted later. I recall being in a meeting with an executive at a company with a robust Six Sigma program. When asked about the value that Six Sigma had brought to his organization, he was very complimentary but said the following in a moment of candor, “Unfortunately, Six Sigma has helped us solve the same problems and capture the same money over and over again.”

The point he was making was not that there is an issue with the methodology, but that the company had failed at some basic level to institutionalize certain improvements…in other words, they weren’t sustained.

At the macro level sustainability is achieved when the organizational paradigm has fundamentally shifted such that it could never go back to operating the way it did before structured improvement was introduced. Characteristics of a stage 3 organization include:

- There is a common language and approach to improvement across the organization (i.e., employees know and speak the language of improvement).

- The vast majority of improvements are operations driven instead of specialist driven.

- A robust oversight/governance process is no longer required to ensure that structured improvement takes place.

- The structured improvement program has survived and thrived through one or more transitions in leadership.

In a related article, I attempt to provide guidance on how to implement a continuous improvement program that is truly sustainable. Long story made short, just like the organization has to make a commitment to migrate from stage 1 to stage 2 in the improvement journey, it has to do the same to migrate from stage 2 to 3. Otherwise, the program will live under the constant threat of regression and concern that hard fought progress will be lost.