Staying Alive: Rescue Mission for Disco-era Satellite

WASHINGTON - It's plunging back through space, but also back through time, and a band of veteran scientists are determined to save it: a lonely satellite from the age of disco, floating homeward without a mission.

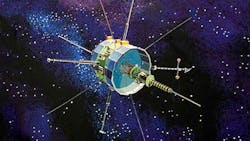

The International Sun-Earth Explorer, or ISEE-3, was built in 1978 to study the physics of solar winds.

In 1981, the spacecraft was sent off on a new mission on a wide orbit in search of comets, and now it is flying blind and NASA has written it off as dead.

But, as it nears Earth once more, some scientists want to return it to its original job, including Robert Farquhar, now in his 80s, who was responsible for hijacking it in the first place.

Farquhar's dream inspired a rescue team, many of them elderly engineers like himself still familiar with the mid-20th century technology on the satellite.

But this band of space enthusiasts won't find it an easy task.

"This is a spacecraft from the disco era. Your toaster is smarter than this," said Keith Cowing, joint leader of the project to reboot ISEE-3.

"The original hardware and software no longer exist. You need that to talk to the spacecraft," Cowing told AFP, explaining how they had to search tons of old files -- "mostly sitting in people's garages."

Veteran Scientists, Junior 'Geeks' Collaborate

"There are lot of people on our team in their 70s and 80s who worked on this originally," Cowing said, alongside more junior "geeks" in their 20s and 30s.

So far, they've succeeded in locating and receiving signals from the spacecraft.

The next step is to send a message to ISEE-3, and see if it hears and can respond, and then they will "tell the spacecraft to do something, and have the spacecraft do it."

Cowing said there's about a 50-50 chance any of this will work.

"The fact that this spacecraft has been left on since 1978, imagine having a TV set, leaving it on."

"It still works; it's sending a radio signal," he said.

But it's another level of complexity, he warned, "to fire the rockets and put it into orbit."

'Because We Can. It's Cool.'

If everything goes according to plan, the so-called "citizen scientists" behind the project, some volunteering their time and equipment, some paid for out of more than $142,000 raised on a crowd-funding website, will try to get the spacecraft into its new orbit by mid-August.

After that, they're going to try to get all the old scientific instruments back up and running.

But why bother rebooting a decades-old satellite?

Cowing said a big part of the answer is, "because we can. It's cool."

Besides, he said, "the spacecraft has a lot of its original science capability. It can provide data that is actually useful."

Princeton mechanical and aerospace engineering professor Jeremy Kasdin suggested a better question might be: "Why not?"

Sure, a modern satellite could perhaps do the job better.

"But it's not like we're going to turn around and build a satellite that's much more capable," because NASA is working on different priorities, said Kasdin, who is not affiliated with this project.

Nor can NASA itself afford to keep all its old projects operational.

"So if there's an opportunity that comes along" to find another way to fund an older mission, "that's always better than not. It's data as opposed to no data."

And even if the instruments no longer work well, the endeavor still could provide useful information about what happens to a spacecraft after 30-plus years "flying around in the radiation environment of the inner solar system," Kasdin noted.

Copyright Agence France-Presse, 2014

About the Author

Agence France-Presse

Copyright Agence France-Presse, 2002-2025. AFP text, photos, graphics and logos shall not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten for broadcast or publication or redistributed directly or indirectly in any medium. AFP shall not be held liable for any delays, inaccuracies, errors or omissions in any AFP content, or for any actions taken in consequence.