Young Entrepreneur Aims to Send 3D-Printed Rockets to Space

To see Tim Ellis hunched over his laptop, alone in a room at a major space industry conference in Colorado, you can hardly imagine that he might be the next Elon Musk.

But Relativity Space, the company he co-founded in December 2015 with the vision of launching 3D-printed rockets, has grown from 14 to 80 employees in one year and will recruit another 40 this year.

At age 28, Ellis has lured several industry veterans, including from SpaceX, the U.S. market leader for launches that was founded by billionaire entrepreneur Musk.

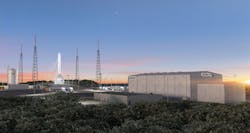

Relativity Space has raised $45 million so far, Canadian satellite operator Telesat has entrusted it with the launch of part of its future 5G satellite constellation and the US military has given it a launch pad at Cape Canaveral.

And Ellis, who six years ago was still studying for his masters in aerospace engineering at the University of Southern California, now sits on the White House's National Space Council along with former astronauts and the heads of the largest American aerospace groups.

"I'm the youngest person by more than 20 years, and we're the only venture capital-backed start-up," Ellis said during the 35th annual Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, a major annual event for the space industry that will welcome 15,000 participants from 40 countries.

Dozens of start-ups have announced plans in recent years to build small and medium rockets to launch small satellites. Many will probably fail before having made their first rocket, but that's the game, Ellis explained.

"The notion in Silicon Valley is you're going to take tons of big bets, where lots of them will totally lose money. But the ones that succeed will pay for all of the losers -- and in a huge outcome, if it's the next Google or the next SpaceX," he said.

Relativity Space, which like SpaceX is based in Los Angeles, has so far printed nine rocket engines and three second stages for its rocket model, called Terran 1, whose first test flight is scheduled for the end of 2020.

Small Satellites

With its large 3D-printing machines, the startup claims that its rockets will require 100 times fewer parts than traditional rockets.

"We'll only be experts in like two or three (technological) processes," he said, compared to traditional manufacturing with complex supply chains. "It's far easier."

Only the electronics are not 3D-printed.

"It's much cheaper, because of the labor reduction in the automation with 3D-printing," said Ellis, who will charge $10 million for a launch, at least at first.

"Also, it's more flexible," he said: eventually, Relativity Space will adapt the size of the fairings of the rockets to the requirements of individual customers, depending on the size of their satellite.

Speed is the other advantage: "Our target is to get from raw material to flight in 60 days," Ellis said.

If Relativity Space succeeds in this feat -- which it has not yet demonstrated -- it would revolutionize the launch industry. Today, a satellite operator can wait for years before having a place in the large rockets of Arianespace or SpaceX.

The Terran 1 will be 10 times smaller the SpaceX Falcon 9, able to place a 2,755 pounds payload into very low orbit 115 miles above the Earth's surface.

This could be suitable for a constellation of small satellites for telecommunications or imaging the Earth, but also for one of the largest customers in space: the U.S. military.

This is another reason for the young executive's arrival in Colorado Springs: meeting senior Pentagon officials.

"I rarely wear a suit, but I will for the military," Ellis said.

By Ivan Couronne

Copyright Agence France-Presse 2019

About the Author

Agence France-Presse

Copyright Agence France-Presse, 2002-2025. AFP text, photos, graphics and logos shall not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten for broadcast or publication or redistributed directly or indirectly in any medium. AFP shall not be held liable for any delays, inaccuracies, errors or omissions in any AFP content, or for any actions taken in consequence.