Auto Slowdown Flashes Caution Lights for Manufacturing Growth — and Trump

After a good run, warning lights are flashing in the auto industry—and that’s not good for either the broader manufacturing sector, heartland metropolitan areas, or President Trump.

Here’s the problem: After seven strong years of growth after the crack-up of the 2008 economic crisis and federal bailouts of both GM and Chrysler, auto-sector output and employment growth have slowed markedly from record levels. Years of catch-up purchases by car buyers have finally plateaued. Likewise, automakers need to economize in order to invest billions in developing the electric and self-driving cars of tomorrow.

And so the layoffs have begun. Last fall, Ford jolted the industry by saying sales had peaked and projecting a tough 2017. Then came the company’s April disclosure that will need to slash $3 billion in costs in order to free up money to invest in new technology. Soon after that came Ford’s announcement of layoffs of as many as 20,000 workers world-wide, and word that GM has cut production at four of its U.S. assembly lines and would be laying off about 4,400 factory workers. Fiat Chrysler also laid off 1,300 workers at a Detroit assembly line.

By themselves, these announcements are not apocalyptic, as were the dire layoffs of 2008. Rather, the recent cuts mostly reflect the fundamentally cyclic nature of a huge consumer business. And yet, the present and future auto slow-down is a big deal, because auto is critical to the manufacturing sector, which in turn looms large in regional and presidential narratives about whether the country is moving “in the right direction.”

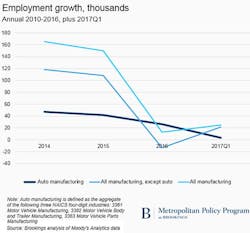

Auto-related industries, after all, delivered about 40% of all of the nation’s manufacturing employment gains in the last two years, given the slow growth of other production sectors in the face of a strong dollar and global headwinds. Focus on just last year and the first quarter of this year, though, and the data show that auto represented fully 80% of U.S. manufacturing employment growth, even as auto hiring slowed significantly. Since then, the trend line has been blurry, but it’s unclear whether other industries—such as chemical manufacturing—are going to be able to pick up the slack from a likely auto-sector slowdown.

For a glimpse of what’s at stake, see here how manufacturing-sector growth turned negative in some 48 of the nation’s largest 100 U.S. metropolitan areas in the 15 months ending in March:

Which is why President Trump and congressional Republicans—along with regional economic development leaders from Kenosha to Lordstown to Flint—had better be hoping for a pulse of factory hiring outside the auto sector. To the extent that auto industries won’t likely be able to carry the mantle of a manufacturing revival in the next year, other production industries are going to have to step up to confirm that working class hiring is up—or next year’s mid-term elections may get dicey.

To be sure, a number of new petrochemical plant openings along the Gulf Coast made possible by cheap and plentiful natural gas may well represent the next new source of manufacturing-sector job-creation. And recent months have seen the economy adding a modest number of manufacturing jobs—about 30,000 a month in the first quarter. However, those gains were later revised down and the economy actually lost 1,000 manufacturing jobs in May. Moreover, none of this is anywhere near on track to delivering the “millions” of manufacturing jobs Trump has promised to “bring back.”

All of which underscores how important the nation’s auto industry has become to the success of the nation’s manufacturing sector—and ultimately to Presidents Trump’s core promise to “make America great again.” With fewer other manufacturing industries turning in substantial employment numbers, much more hangs on the continued employment growth of the auto sector today than a decade ago. A true slump in the enormous auto sector like the one that appears in the offing could prompt new frustration in the “battleground” metros and congressional districts of Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania.

Mark Muro is a senior fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings. Dustin Swonder provided analytic and graphics help with this article, which appeared originally on Brookings' The Avenue blog.