OPINION

China’s economy began to enter a structural slowdown even before the pandemic. Its seemingly unstoppable growth model proved less sustainable than originally thought. The 4D’s—demographics, debt, drought and decoupling—weigh heavily on China’s economy.

Demographics: China’s population is shrinking. Birthrates in China are falling, and its population is aging. The number of births dropped to 9.56 million in 2022, the fewest since 1790. By 2035, 30% of China’s population will be 60 years old or older. China’s labor shortages and rising wages are driving some U.S. companies to reevaluate the profitability of manufacturing or sourcing in China, as Chinese exports become less competitive.

Debt: As exports decrease, Beijing bolsters the economy by pumping money into the system with investments from state banks and local governments. But funding is typically prioritized to conform to the authoritarian government’s ambitions, rather than based on risk-return calculations. Risky investment activity has led to inflated real estate, land bubbles and unsustainable debt. According to the World Bank, “No country in history has amassed so much debt so quickly as China has without succumbing to a financial meltdown.”

Drought: Water scarcity is threatening China’s industrial base. Climate change is expected to exacerbate the problem. Retreating glaciers, disappearing ice cover, increasing temperatures and China’s unequal water distribution are contributing to China’s water shortage crisis. Eighty percent of China’s water is concentrated in South China, even though the nucleus of its national development is in the north, including the three heavily industrialized provinces of Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei.

Decoupling: These 3D’s plus geopolitical risk are driving the 4th D. The perception that investing in and sourcing from China was risky business suppressed foreign direct investment (FDI), an important driver of China’s economy. China’s FDI toppled to $20 billion in Q1 2023, compared to $100 billion in Q1 2022. In Q3 2023, China’s FDI turned negative for the first time on record. FDI into China plummeted 82% in 2023 year over year, to $33 billion, the lowest figure since 1993. In sharp contrast, the U.S. was the top FDI recipient globally in 2023 (USD 341 billion).

China’s slowing growth prospects made the local market less attractive. Foreign companies’ worries include a wave of raids, investigations and detentions and an expanded anti-espionage law. Business activities like market research could now be considered spying.

Many companies built factories in China to sell to that huge, growing middle-class market in China that is not cooperating by saving less and consuming more. Instead, China is increasing factory capacity to export more to European and American consumers, whose countries are resisting more vigorously than in the past. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said the U.S. wouldn’t take “anything off the table” including the possibility of additional tariffs, while the EU indicated it had tools to protect its market, referring to tariffs.

As foreign companies reduce their investment, growth declines, making China a less attractive market, further reducing investment. China’s 30+year virtuous spiral has turned negative.

Pandemic Impact

The systemic shock from the pandemic and the “-COVID” lockdowns exposed and exacerbated China’s structural weaknesses. China’s economic growth of 6 percent dropped to 2.2% in 2020. The pandemic and prolonged strict policies stunted consumer demand, production, investment and international trade. Overall, the impact of China’s strict pandemic policies was vast.

COVID-19 Pandemic: First Wave

Initially, China shut down the economy quickly and oppressively. Around that time, many Western companies stopped importing Chinese goods as they weighed the risks of remaining in China. Economic disaster seemed imminent. But by Q3 2020, China was the first world economy to grow again, and the seemingly resilient Chinese economy was back in the black by year’s end.

COVID-19 Pandemic: Second Wave

The second wave of the COVID pandemic was a totally different scenario than the first. China again employed strict lockdown measures and restrictive policies. But the pandemic exacerbated China’s structural weaknesses. By Q2 2021, problems with China’s real estate and banking sector surfaced, causing financial distress. At the same time, strict COVID lockdowns decreased consumer spending, factory production and FDI.

By Q4, 2022 countries worldwide had lifted COVID restrictions, but China persisted. Lockdown measures stayed in place, and the Chinese economy began to lose ground through 2022.

To mitigate supply chain risk, multinational companies reconfigured supply chain strategies, choosing localization, China +1 or an “anywhere but China” policy to reduce over-reliance on uncertain Chinese policy.

2024 Global Backlash: China Shock, the Sequel

China’s economic growth slumped to a three-decade low in 2023 (5.2%), and is expected to slow to ~2% by 2030, according to London-based independent research agency Capital Economics. In an effort to engineer an economic turnaround, Beijing plans to double down on production capacity and flood the global market with cheap goods. The first ‘China shock’ (2000 to 2012) decimated industries worldwide, costing the U.S. alone millions of manufacturing jobs.

The world is not interested in experiencing the sequel.

Beijing’s export-driven policy will put China on a collision course with national self-interest around the world. Fitch, one of the Big Three credit-rating agencies, cut China’s ratings outlook to negative in April 2024, citing public-finance risks based on increasing economic uncertainty as China shifts to new growth initiatives.

Geopolitical Risk

China is the epicenter of two powerful forces driving reshoring. Geopolitical concern is the #1 factor. COVID shutdowns, the war in Ukraine, the Israeli/Hamas conflict and increasing tension over Taiwan show that it is past time for companies to evaluate reshoring and nearshoring as “insurance” against catastrophic disruptions. Chief Executive magazine’s 2023 survey confirmed that “geopolitical risk exposure” is the most highly ranked of the “main drivers for reshoring operations.”

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) is increasingly important, and China creates the most emissions—12.7 billion metric tons of emissions annually—due to its reliance on coal. For many products, emissions from production and shipment from China to the U.S. are 25% higher than sourcing domestically. Countries will impose tariffs based on emissions.

Revised TCO estimator

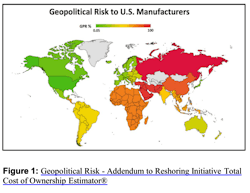

Companies can use the Reshoring Initiative’s free online TCO Estimator and our new Geopolitical Risk measure (Figure 1) to compare alternative sources. Geopolitical risk (GPR) is the probability in one year of a major disruption in trade resulting in the cessation of exports from that country to the U.S. as a result of an adverse geopolitical event. Detailed risk values are at the linked site.

User data shows that 20% or 30% of what is now imported from China can be sourced domestically at equal or greater profitability. A revised TCO version, expected to be online in late 2024, will include the geopolitical risk factor and should drive that percentage to well over 50%.

The revised estimator will use geopolitical risk to calculate the expected value of lost margin on revenue due to stocking out of a component or product. By including that cost in Total Cost, the user can determine whether it makes sense to “insure” its supply chain by reshoring.

Are you thinking about reshoring?

For help, contact me at 847-867-1144 or email me at [email protected]. Our main mission is to get companies to do the math correctly using our free online estimator. By using TCO, companies can better evaluate sourcing, identify alternatives and even make a case when selling against offshore competitors.

Harry Moser is founder and president of the Reshoring Initiative.

About the Author

Harry Moser

Founder

Harry Moser, founder of the Reshoring Initiative, grew up experiencing the glory of U.S. manufacturing. With more than 45 years of manufacturing experience (most recently 25 years as president, chairman and then chairman emeritus of GF AgieCharmilles), Moser is a leading industry spokesman for reshoring and for developing the skilled manufacturing workforce required by reshoring.

The not-for-profit Reshoring Initiative ‘s Mission is to bring back U.S., and more generally North American, manufacturing jobs by helping companies see that, increasingly, they will be more profitable if they produce and source in or near their market.