Despite rising payroll taxes, the uncertainty over global economic growth and the U.S. government’s tendency to play political hopscotch from one crisis to another, my company Riverwood Solutions is hiring. Since the new year began, we have added a handful of jobs in the U.S. as well as a couple of jobs in both China and Mexico, which is significant for a company of less than 100 people.

I was reviewing resumes the other day and found myself uncharacteristically excited by the skills, experience, and especially the education of a particular candidate. I could not remember the last time I had seen a resume where a candidate had a Master of Science in Industrial Engineering (go Boilermakers!). I can remember quite a bit earlier on in my career, a number of my peers and managers were “IEs” by training and at that time the manufacturing employment base of the U.S. was far higher than it is today. But for whatever reason, industrial engineering seems to be viewed by college students as a bit of a dinosaur and perhaps not as practical a field of study in today’s globalized and outsourced world as other fields such as Elizabethan literature, Etruscan studies or paleontology.

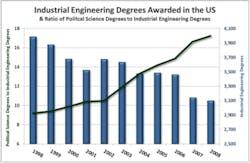

So I spent a bit of time on line and with our research department and came up with some interesting stats about industrial engineering studies in U.S. colleges and universities. In the top 100 schools for industrial engineering in the U.S., there are a total of just 5,360 students that have IE as their declared major. In fact, there are twice as many college students studying political science in California than are studying industrial engineering in the entire U.S. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are only about 200,000 industrial engineers in the U.S. and this number will grow by a total of just 6% over the next decade - a career path that the BLS flags as having “below average growth.” In defining the job of industrial engineers, the BLS says the following:

What Industrial Engineers Do

Industrial engineers find ways to eliminate wastefulness in production processes. They devise efficient ways to use workers, machines, materials, information, and energy to make a product or provide a service.

Now what does it say about America’s foundation for industrial growth and manufacturing revival when the CEO of a firm such as mine, that does nothing but help companies with their manufacturing and supply chain, finds himself almost giddy at stumbling across a single highly skilled manufacturing professional with an M.S.I.E.? It says, in part, that our country is losing its base of capabilities from which to build and rebuild its industrial might.

Tax Policy is Not an Industrial Policy

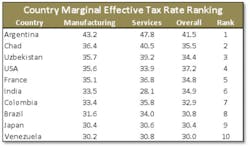

Despite the ever rising din of voices clamoring for the U.S. government to help promote manufacturing jobs, 90% of all the ideas and conversation I hear out of Washington on this issue focus on cutting corporate taxes. Yes, marginal U.S. corporate tax rates are too high and are increasingly helping to dissuade companies from making significant additional investments in productive industrial assets in the US. Notwithstanding all of the market attractiveness and other benefits of locating industrial assets in the U.S., the fact that only Argentina, Chad and Uzbekistan tax the corporate profits from these assets at a higher rate than the U.S. is a significant disincentive for new manufacturing investment.

Make no mistake; we need corporate taxes reform – yet tax reform alone will not create the manufacturing jobs the U.S. is looking for. I know, because one of the things my company does in helping our clients optimize manufacturing and supply chain is to facilitate offshore production when that is deemed to be the best option. Rarely have we seen the decision to offshore production be one that is made based on corporate tax rates being the primary consideration, but it is almost always influenced significantly by the availability and cost of skilled labor.

The decision to outsource production offshore is one that is generally made with a thoughtful analysis of all of the various costs, and with the goal of capturing more customers and enhancing shareholder value. Many variables play into this type of analysis including numerous components of manufacturing costs such as wage rates, regulatory costs, length of product life cycles, availability of skilled workers, freight costs, productivity, energy costs and more.

To truly understand how to create more manufacturing jobs in the U.S., our leaders must first develop a meaningful, non-rhetoric-based understanding of why manufacturing jobs move offshore or why new jobs are created offshore – and the reason is quite often cost. In some industries, addressing this cost gap is a waste of time as the differences in input costs are too great to overcome, and the jobs lost are not the jobs that the U.S. needs. But in many industries, the attractiveness of offshore production could be significantly reduced, over time, by thoughtful long-term policy actions aimed at making the U.S. more competitive. That is not to say that I am in favor of a Jimmy Carter-styled “Industrial Policy”, but I am fully in support of developing government policies that strengthen the foundational elements of our manufacturing industries. Let’s call it the “Industrial Foundation Policy.” And for the sake of my limited word count for this article, I’ll focus on education.

Education is Key to Industrial Advancement

One of the key components to an industrial foundation policy must be an education system that addresses all of the various skills needed for manufacturing jobs at all levels. In the U.S. only about 3 out of every 4 students entering high school actually graduate, with roughly a third of these entering college. This contributes significantly to the problem of youth unemployment, which today stands at about 16%. The problems with low graduation rates, and the quality of education received by those who do graduate, make it very difficult for high-tech manufacturers to have confidence in an ongoing supply of new skilled workers.

By contrast, Germany’s youth unemployment rate is currently around 7.8%, due in part to its dual-track education system that includes a well-established system of apprenticeships and vocational training as an alternative to traditional university studies. Fully 60% of high school graduates in Germany follow the vocational training and work apprenticeship route and develop meaningful job skills including many aimed specifically at high-tech manufacturing. This is a training path that is sorely lacking in the U.S., excepting of course for the significant amount of on-the-job training available to America’s next generation of baristas.

The availability of skilled workers does not simply mean a trained and educated labor force for the factory floor. The skill sets required for industry include considerable numbers of well-paid support staff with higher education in math and science, business management, accounting and finance, supply chain management, environmental systems, material science and numerous other disciplines. Much of the higher education that America needs for a significant industrial renaissance is becoming financially out of reach for many in the middle class. Of course there are grants, loans and scholarships available. But for the most part U.S. policies have made no real attempt to influence the supply of college graduates completing studies in those fields that have the greatest impact on manufacturing jobs, industrial productivity and industrial output. Perhaps the student loan guarantee system in the U.S. needs to be restructured – not to make it harder to get a degree in fine arts, but to create additional enticements for more new college students to pursue math, science and engineering – maybe even industrial engineering.

And speaking of industrial engineering, the 5,360 college students currently majoring in industrial engineering across the U.S. in total are spending $139.2 million a year on this very valuable education that is of critical importance to our country’s manufacturing base. That number is roughly 1/10thof what Apple spends annually on the air freight required to ship manufactured products from China to the U.S.

Contributing Editor Ron Keith is chief executive officer for Riverwood Solutions, a supply chain consulting and managed services firm.

About the Author

Ron Keith

Chief Executive Officer

Ron Keith brings more than 24 years of operations experience to Riverwood Solutions including engineering, manufacturing and executive management positions at Westinghouse, Wavetek, Rockwell, Alcatel and Flextronics International. Ron has a reputation as an innovator, team builder, creative problem solver and strategic thinker who delivers straight talk and strong results to Riverwood's clients. He has run international EMS operations with annual sales in excess of $1.4B and has managed manufacturing, product development, and program management personnel in numerous countries.

Ron has advised more than four dozen companies on their manufacturing operations, supply chain, and outsourcing strategy including more than a dozen Global Fortune 500 companies. He has previously consulted for four of the top 10 EMS (Electronic Manufacturing Services) companies and has advised hedge funds, private equity funds and strategic investors on a number manufacturing services related investments. Ron has published more than 30 articles on various manufacturing, technology and business related topics including strategy, operations, quality management, technology trends, and supply chain management.

Prior to founding Oreamnos Partners and Riverwood Solutions, Ron served as Vice President and General Manager at Flextronics International, where he started and ran several divisions in both the EMS and ODM (Original Design Manufacturer) spaces during his more than eight year tenure. He worked with, and ran manufacturing operations for, a number of leading OEMs at Flextronics including Cisco, Motorola, JDS Uniphase, Nortel. W.L. Gore, Kyocera and others.

Ron has undergraduate degrees in both Electronic Engineering and Manufacturing. He received an MA in International Management and an MBA in Operations Research from the University of Texas at Dallas, where he also completed the majority of coursework towards a Ph.D. in Organization, Strategy & International Management (OSIM).