The Key to a Successful Lean Journey? Leadership!

Although the official percentage is debatable, on average well over 60% of lean transformation efforts fail. With so many resources available today, from books to articles to consulting firm after consulting firm, how could this be?

Many would say inadequate training, limited internal resources, lack of understanding of the tools associated with lean, not enough time, or inadequate funding, among other reasons.

While each of these is valid, many years of experience in driving lean initiatives and observing first-hand the pitfalls, learnings and the "dos and don'ts," of many lean journeys, I believe it comes down to one key element that must be present above all others: strong leadership.

What do I mean by strong leadership within a lean organization? In an organization attempting to transform itself into a true lean enterprise, this means strong, passionate leaders at the top of the organization who either innately possess or have learned a series of foundational behaviors and values, and who role model these every day.

So what are these values and behaviors, and how does a leader go about teaching and applying them to the broader organization?

Key Qualities of a Lean Leader

Although great leaders possess a host of values and qualities that set them apart, leaders within an organization striving to become lean display a series of very specific and necessary qualities. Among these, discipline and humility form the foundation. Why discipline (and by this I really mean personal or self-discipline)? Because lean transformations and change management efforts are difficult, draining, often thankless undertakings. While the rewards pay off for years to come, a very regimented, highly disciplined approach to daily work is required to reinforce the focus on standardization and to ensure the organization remains optimistic about the future.

The most powerful yet often overlooked aspect of a lean enterprise is standardization (See "Standardization: The key to building a learning organization"). If the people within the organization are being asked to structure and standardize their activities to learn and improve, it must start with the leaders' own work and business processes. In addition, the only way to drive improvement is through a methodical application of the scientific method/Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) process to problems and opportunities. Thus, due to the ongoing, daily focus on standardization and application of PDCA by "everyone, everywhere, every day," long-term efforts are destined to fail without a strong sense of personal discipline from the leaders of the organization. If leaders role model discipline, others closely follow from sheer example.

When we think of strong leaders, we often think of tough, dynamic, assertive, command-and-control-type of people. Yet, why is it important for leaders within a lean organization to be humble? Before we answer this, let's start with another question: What is the ultimate goal or "holy grail" of a lean enterprise? Opinions vary, but in it's most simple form, the ultimate destination is to become a learning organization; that is, the emphasis shifts from a pure results orientation to constantly asking the question, in both good and bad outcomes, "What did we learn from this?" This then leads to the question, "What can we change or improve next time?"

So how does humility play into this concept of a learning organization? We can probably answer this ourselves by reflecting back on our own experiences with no-so-humble leaders. Is an arrogant or proud leader open-minded and in a position to learn from his or her successes and mistakes? Unlikely. A humble person is in a much better position to be open to new ways, new ideas, and improvements. The dangers of becoming too proud or satisfied with our current performance can be noted through many examples - the Roman and British empires, the Soviet Union, not to mention GM, IBM, Delphi, and Enron, to name a few. But for a lean organization, the greatest threat of all is the re-emergence of waste. One of the most significant benefits of going lean is the reduction of waste. Complacency and a state of satisfaction are completely contrary to what we are trying to build within a lean enterprise because they allow waste to creep back into the system. It's much easier to maintain low levels of waste than to remove it all over again. Hence, humility is an essential quality of a leader and forms the foundation for developing a learning organization.

Key Roles of a Lean Leader

Although leaders at the top of the organization wear many hats and are required to fulfill countless duties, within a lean enterprise, only four are critical to making the new culture stick:

- Removing ambiguity by teaching the organization to structure and standardize its activities;

- Reinforcing and working on the system by helping people identify and solve problems;

- Constantly setting the vision and ideal state which creates healthy tension in the system; and

- Practicing new learnings through application, application, application.

Let's explore removing ambiguity. Ambiguity creates an enormous amount of waste and makes it virtually impossible to identify and solve problems. How much more effective and efficient could the entire organization be if the leaders spent a majority of their time teaching and helping associates to remove ambiguity? This is the kind of work that generates step-function level improvement, not just incremental. The way to remove ambiguity in daily tasks and activities is to structure and standardize those activities. Leaders must insist that every level of the organization be very clear about the inputs, connections, flows, requirements and outputs of their work. This is a long, arduous process, and it can take years to achieve what we would consider a reasonable level of standardization. However, since this is the most difficult of all the elements to attain, leaders need to remain resolute about driving the focus on removing ambiguity within the enterprise.

The next critical role leaders play within the organization is working on the system, and specifically, ensuring people are constantly finding ways to make problems evident and then applying the right tools and methods to address those problems. If you boil down the Toyota Production System (TPS) into its purest form, literally everything is designed to do two things: identify problems and solve problems. (Of course, lean purists don't consider problems ever to be truly solved but rather countermeasures are put in place to address the root causes of those problems.) 5S, process mapping, A3s, kanban, andons, etc., are all simply tools to help people make problems evident and solve them rapidly to keep the organization moving forward.

The role of a leader within a lean enterprise is to reinforce these practices and ensure the people have the resources necessary to do their daily work. A single problem is often the result of a series of related problems, so what may initially appear as a simple issue is often a symptom of deeper, underlying issues that are occurring within the system around the various activities, connections and flows of goods, people and information. While it's easy to fall into the trap of working "in" the system, leaders should resist this temptation and instead look at the bigger issues and work "on" the system. These actions help the organization much more in the long run. In addition, as problems are identified, what does a leader do in response to the andon cord "pulls" and other calls for help? Very simply, go to the point of activity, where the problems are, and ask, "What's the problem and how can I help?" These two embedded questions will help uncover what's broken in the system and direct leaders to work on removing roadblocks and broader levels of waste within the organization.

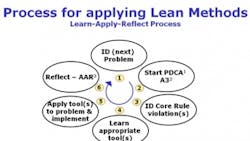

Once we understand this role, there's a very straightforward process that leaders can utilize to help further build a learning organization. The cycle looks like this:

One can quickly see the straightforward, repetitive process that leaders can use to work on the system, and to teach and build a learning organization over time.

Thirdly, one of the greatest reasons so many change management efforts fail is the lack of a clear vision. As the enterprise embarks on a long-term lean journey, it's essential for leaders to continually paint a picture of where the organization is headed. People need to know where they're going and what the ideal state of their enterprise looks like. A major reason for this is to build healthy tension in the system. A "healthy tension" means building that state of dissatisfaction with where you're at versus where you're trying to go. If we know a substantial gap exists between where we are and what ideal looks like, then we know we need to stay disciplined, focused and resilient in working on our processes.

Before communicating to the masses about your lean journey and why it's essential to the organization's survival, it's important to first be very clear about where you're going. If you can't convey the vision or ideal state in the form of an "elevator speech," then you're not ready to launch the transformation. Generally, the ideal state needs to include not just what but how it looks. For example, "To be the best widget factory in the world by delivering exactly what the customer wants, exactly when they want it at the price they want with zero waste and everyone safe." Having a vision of being the best factory in the world doesn't help people internalize what that means and how they're supposed to get there. By including elements of what the business needs to deliver removes that ambiguity.

Application, Application, Application

Finally, we arrive at one of the most challenging roles a leader plays, because it's often very uncomfortable and reveals our vulnerability -- and this is the daily application of our learnings. Just as real estate people say the most important aspect of a property's value is "location, location, location," the most important part of developing a lean enterprise is application, application, application.

The barrier to shifting people's way of thinking about their work is not cognitive; that is, we can read an article on lean, and say "Oh, I get it," and certainly the concepts and theories behind what we read may be obvious. But we'll never fundamentally change the way we see the world and how we behave until we start applying those concepts to our own work on a regular basis and take the time to reflect on what we learn from those applications. This is why I personally emphasize as little training as possible in lean transformation efforts and focus instead on applying the concepts to our daily work.

Let's face it, adults are difficult beasts not only to teach but also to get to change their behaviors. We like doing things "our way" and are comfortable doing things the way we've always done them. Hence, the only way to get us to open up our minds to seeing things differently is by using our "hands," if you will, through application. For example, how would we go about getting a small group to implement a 5S program? Start with a little overview of what 5S is via some reading and perhaps a brief class on the topic, but then go to the point of activity and start doing 5S. This is the application piece. If we simply read a book on 5S, take a class and then "check the box," we haven't changed anything about our work and our behaviors. This can only be done by applying the concepts and in fact implementing the necessary steps to develop a neat and tidy workplace (the basic outcome of 5S).

In summary, one could cite many reasons why lean journeys fail, but it's important to ensure strong leadership isn't to blame. The fundamental qualities of a successful lean leader are discipline and humility, which go hand-in-hand. Once these qualities are embraced and internalized, the four critical roles of lean leadership can more easily be learned and applied to all levels of the developing lean enterprise.

Kurt Woolley holds a master's degree in industrial engineering and has been with Intel Corp. for 17 years. He has held numerous positions in operations, including manufacturing supervisor, process and equipment engineer, manufacturing engineering group leader, and his current role as strategic program manager. Over the past six years, he has focused extensively on lean manufacturing implementation methods within Intel's fab/sort manufacturing organization, is a Shingo Prize award judge, and has received extensive training through the Lean Learning Center in Novi, Mich.