ITIF Report says Productivity Should be the Principal Economic Policy Goal

On May 5, the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF) released a 124-page report, "Think Like an Enterprise: Why Nations Need Comprehensive Productivity Strategies,” by Robert D. Atkinson, president of ITIF.

Atkinson opines that "Increased living standards depend on increased productivity. But productivity growth will lag unless governments implement smart productivity policies. To be effective, these policies need to go beyond the conventional solutions grounded in neoclassical economics and embrace four other key components: incentives, including tax policies, to encourage organizations to adopt new tools to drive productivity; policies to spur the advance and take-up of systemic, platform technologies that accelerate productivity across industries; a research and development strategy focused on spurring the development of productivity-enabling technologies such as robotics; and sectoral productivity policies that reflect the unique differences between industries."

He states, "Finally, for nations to put sophisticated productivity policies in place, the single most important step is to establish productivity as the principal economic policy goal, ahead of other factors such as stable prices or low employment."

The report is divided into three parts: Part I provides an "overview of productivity, including what it is, why nations need to accelerate it, and how it grows through shifts in enterprises and technology…Part II provides a framework for thinking about national productivity policies," and "Part III lays out a comprehensive agenda for spurring productivity growth, which most nations can use as a guide in tailoring their own national productivity policy agendas."

Breakthroughs in materials science, some of them fueled by the Materials Genome Initiative, and technologies like nanotechnology are enabling stronger, lighter, and more durable materials, all of which would boost goods-sector productivity.—Robert D. Atkinson

I like his simple explanation of what productivity is and is not. He states, "Productivity is not a measure of how much an economy is producing…(gross domestic product, or GDP)…Nor is productivity a measure of how many hours people work….Rather, in its simplest form, productivity is a measure of economic output per unit of input (i.e., it is an efficiency measure). The unit of input can be labor hours (labor productivity) or all production factors, including labor, machines, and energy (total factor of productivity)."

He explains that you can increase productivity by working harder or faster, working "more efficiently by reorganizing work processes and providing better tools, or by using better technology or business models to completely eliminate the need for some work." However, he clarified that there are "two related measures of productivity: labor productivity and total factor productivity. Labor productivity is… the output of workers divided by the number of hours of work. Total factor productivity is broader and is a measure of the productivity of all factors of production, including workers, energy, and machines. An economy might increase labor productivity by adding more machines, but total factor productivity could go up or down depending on whether the machines’ output is worth its cost."

Not only does increased productivity increase living standards, "productivity is the key to income growth…historically, labor productivity increases have been the major contributing factor to growth in real GDP per capita.”

Additionally, "Productivity growth is also vital to eradicating poverty... the commonly accepted view that productivity growth has not benefited lower income workers in America is not true."

One important reason that nations should focus on improving productivity is that "Higher productivity plays a key role in increasing governments’ fiscal health. Higher productivity leads to higher incomes, which in turn lead to higher tax payments from companies and individuals. Moreover, higher productivity leads to reduced expenditures (on items such as income support for low-income individuals)."

In my presentations on how to return manufacturing to America, I explain that because fewer Americans have the higher paying manufacturing jobs from offshoring manufacturing, fewer Americans are paying taxes resulting in higher local, state and federal budget deficits.

It was eye opening to read that if we could increase the "real rate of U.S. GDP growth over the next decade from 2.8% per year to 4%," we could reduce the budget deficit by $6.8 trillion. Since we only had a 1.4% GDP growth rate for the last three months of 2015 and an average of 0.8% GDP growth rate in the first three months of 2016, you can see why our budget deficits are getting worse instead of better.

Atkinson debunks the opinion of economic pundits who claim that productivity through advances in technology kills jobs by pointing out that "if technology-led productivity growth really has been the culprit behind America’s anemic job growth since 2009," then "one would expect that America’s productivity growth rate would be higher than normal. In fact, U.S. productivity growth since the end of the Great Recession has been at historic lows—about half the rate than previously." He shows that the "productivity kills jobs argument is refuted not only by logic, but also by data and econometric studies."

He states, "Historically, the relationship between productivity growth and unemployment rates has actually been negative." In other words, higher productivity meant lower unemployment. For example, he cites a McKinsey Global Institute report on employment and productivity change from 1929 to 2009 that showed "only 1% had declining employment and increasing productivity" out of 71 10-year economic slices. "The rest showed increasing productivity and employment."

In response to the criticism that automation will kill jobs, he cites the McKinsey Global Institute conclusion that “Very few occupations will be automated in their entirety in the near or medium term. Rather, certain activities are more likely to be automated, requiring entire business processes to be transformed, and jobs performed by people to be redefined." Atkinson concludes, "Far from being doomed by an excess of technology and productivity, the real risk is being held back by too little technology."

With regard to the argument that technology is leading to greater inequality in wealth, he states, "the evidence is quite strong that technology has not been the cause of growing inequality." He adds, "Historically, periods of high productivity have been associated with reduced income inequality, not more. During the 1960s, productivity grew at rates more than twice as fast as it has in the last 10 years. However, income inequality declined while median family wages increased by almost 30%."

Productivity Grows Through Technology

Atkinson asserts that productivity grows through technology ─ "it is better tools, made possible by technological innovation, that enables productivity growth." He quotes Robert Gordon from his book The Rise and Fall of American Growth: “the rise in the American standard of living over the past 150 years rests heavily on the history of innovations, great and small.” He explains that "One key way to develop better tools is through research and development. Numerous studies find that R&D contributes to productivity…R&D accounts for around 1.38 percentage points of annual economic growth."

He explains that "ICT [Information and communications technology] has enabled the creation of a host of tools to create, manipulate, organize, transmit, store, and act on information in digital form in new ways and through new organizational forms…ICT is a key driver of productivity because it is what economists call a general purpose technology (GPT). GPTs have historically appeared about once every half century, and represent systems of fundamentally new technologies that change virtually everything." He states that the principal reason why the use of ICT tools been the key growth driver "is that it has a greater impact on productivity and growth than non-ICT capital."

He discusses how national productivity data usually only goes back to the 1940s for developed nations but may be nonexistent for developing countries. "Even in the most advanced nations, it can be hard to accurately measure productivity and, in particular, output…Output in some sectors, including government and health care, is usually poorly measured…In addition, productivity data measure only market output."

Annual Labor Productivity Growth in the Private Business Sector

1947-1973 2.81%

1973-1995 1.52%

1995-2008 2.42%

2008-2015 1.21%

In a lengthy section comparing U. S. productivity to other major countries, the data show the U. S. is the most productive country in the world. In fact, "Brazil’s and Russia’s productivity levels in comparison with the United States are lower today than they were half a century ago": 24.3% in 1950 vs. 24% today for Brazil and 44.6% in 1960 vs. 41.4% today in Russia.

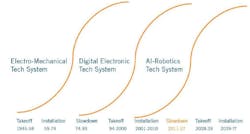

Atkinson points out that "The conventional economics view of innovation, to the extent that economists have one, is that it is linear, something that just happens regularly. But in fact technological innovation appears to follow a pattern of repeating S-curves, waves of technology emerging and then stagnating before the next new wave" as shown by Joseph Schumpeter's chart below:

Atkinson next provides a consideration of the debate that has emerged between what he calls "stagnationists and technooptimists." Stagnationists believe "the U.S. economy has “picked all the ‘low-hanging fruit’ for productivity advancement and is in for a long period of stagnation…” The "techno-utopians proclaim breathlessly that we are poised on the edge of a new industrial revolution, even greater in magnitude than the prior ones. Because of this, the techno-utopians argue that productivity growth rates will soon skyrocket." Atkinson states, "In fact, the truth is likely in the middle."

Part I concludes with a brief overview of "Opportunities for Productivity Growth by Sector.” Atkinson believes that "three main technologies—robotics, new materials, and data science and the Internet of Things—all offer promise. Many jobs in factories are still done by hand that more adept robots could do instead. Breakthroughs in materials science, some of them fueled by the Materials Genome Initiative, and technologies like nanotechnology are enabling stronger, lighter, and more durable materials, all of which would boost goods-sector productivity."

Watch for my next blog article that will feature highlights of Part II and III of this important ITIF report. Good news in the manufacturing sector needs to be relished.

About the Author

Michele Nash-Hoff

President

Michele Nash-Hoff has been in and out of San Diego’s high-tech manufacturing industry since starting as an engineering secretary at age 18. Her career includes being part of the founding team of two startup companies. She took a hiatus from working full-time to attend college and graduated from San Diego State University in 1982 with a bachelor’s degree in French and Spanish.

After graduating, she became vice president of a sales agency covering 11 of the western states. In 1985, Michele left the company to form her own sales agency, ElectroFab Sales, to work with companies to help them select the right manufacturing processes for their new and existing products.

Michele is the author of four books, For Profit Business Incubators, published in 1998 by the National Business Incubation Association, two editions of Can American Manufacturing be Saved? Why we should and how we can (2009 and 2012), and Rebuild Manufacturing – the key to American Prosperity (2017).

Michele has been president of the San Diego Electronics Network, the San Diego Chapter of the Electronics Representatives Association, and The High Technology Foundation, as well as several professional and non-profit organizations. She is an active member of the Soroptimist International of San Diego club.

Michele is currently a director on the board of the San Diego Inventors Forum. She is also Chair of the California chapter of the Coalition for a Prosperous America and a mentor for CONNECT’s Springboard program for startup companies.

She has a certificate in Total Quality Management and is a 1994 graduate of San Diego’s leadership program (LEAD San Diego.) She earned a Certificate in Lean Six Sigma in 2014.

Michele is married to Michael Hoff and has raised two sons and two daughters. She enjoys spending time with her two grandsons and eight granddaughters. Her favorite leisure activities are hiking in the mountains, swimming, gardening, reading and taking tap dance lessons.