The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) was the ultimate test of supply side economic theory, reducing corporate taxes from 35% to 21%, or by $1.5 trillion over 10 years.

Did the TCJA boost manufacturing?

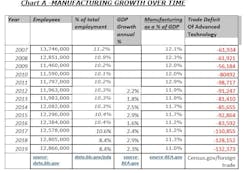

Chart A summarizes some of the economic factors that affect manufacturing growth. It tracks data through 2019, so prior to the pandemic.

Employees: Column 2 shows that manufacturing has added 288,000 employees since the year of the tax cut (2017). This is approximately 2% growth. Column 3 shows that manufacturing employment as a percentage of overall employment has been declining for the last decade. And in Column 5, manufacturing output as a percentage of GDP has been declining for many years. The tax cut does not appear to have had a positive influence on any of these economic factors.

Capital investment: The Bureau of Economic Analysis fixed-assets tables by industry shows manufacturing investment in three categories—private equipment, private structures, and intellectual property in billions of dollars as follows:The capital investment in equipment and intellectual property increased 6%, and the investment in structures declined by 1%. So far, the investment results from the tax cut are very modest, and do not show the big capital investment projected by supporters of the TCJA.

Close to Contraction

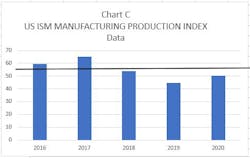

The ISM manufacturing report surveys over 400 purchasing and supply managers about their future expectations on production, inventories, employment, and new customer orders. The benchmark number is 50 for the index. A number higher than 50 represents economic growth, while 50 or lower is considered economic contraction.

Chart C shows that, pre-pandemic, manufacturing was close to contraction for the last 14 months. The latest published index in Industry Week, March 2020, shows that the PMI Index was 49.1% and that manufacturing is now officially in contraction. New orders, employment, inventories, and imports are contracting and prices are decreasing Overall, the 2017 TCJA has not been a boost for the manufacturing sector.

Effects on the General Economy

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin said in October of 2017 that tax cuts would push “GDP growth over 3% or higher leading to millions and millions of jobs.” The economy has not gone over 3% for the last seven years, and GDP growth will probably go negative during the second quarter of 2020.

Perhaps the biggest blunder of the Trump administration was the claim that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act “would add $1.8 trillion in new revenue that would more than pay for the $1.5 trillion cost of the tax cuts themselves.” The implication is that increased economic growth would boost tax revenues enough to offset the tax cuts. But this optimistic scenario simply did not happen.

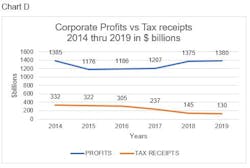

Chart D, based on data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, shows that tax receipts have declined $160 billion since 2016, and $92 billion since the tax cut.

Since the tax receipts are declining and growth is not paying for the tax cuts, the TCJA is simply increasing the federal deficit.

What Did Corporations Do with the Profits?

However, this optimistic scenario did not happen; companies used much of their new profits to buy back shares of their own stock to increase the share price and realize short-term profits. In 2018, stock buybacks hit $800 billion, and in 2019 they were expected to be $795 billion.

In 2018, stock buybacks hit $800 billion, and in 2019 they were expected to be $795 billion.

In the run-up to the vote by Congress for the TCJA, there was no mention of or written limitation for using the new profits for stock buybacks or for dividends to shareholders, and multi-national corporations moved quickly to use the profits for short-term gains, rather than invest for long-term growth.

Besides stock buybacks, American corporations continue to sell, hire, and invest more in their overseas operations than they do in the U.S. facilities. A World Investment Report by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) lists 21 of the largest American multi-national corporations (MNC) ranked by foreign assets.

The list shows that:

1.They have nearly or more than 2/3s of their total sales outside the U.S.

2. They have half of their workforce outside the U.S., and some employ 75% of their workforce overseas.

3. They have half or more than half of their total assets (property, plant, and equipment) located outside the U.S.

The report says that in order to sustain themselves, U.S. multinational corporations are “forced” to “minimize their production costs for their global markets” and are sometimes “required” to “shift production overseas, possibly to take advantage of lower labor costs, lower taxes or more favorable regulations.” So the assumption is that these companies will continue to invest in overseas facilities, not primarily in the U.S.

American multi-national corporations pay very low taxes to manufacturer in foreign countries. In addition, they can defer U.S. taxes indefinitely as long as the profits are held in a foreign subsidiary or in a tax haven like Ireland or the Cayman Islands.

According to the International Tax and Economic Policy Institute, Fortune 500 companies hold $2.6 trillion offshore, avoiding about $767 billion in federal taxes. They are also allowed to deduct foreign expenses like interest, administrative overhead, and R&D against their U.S. tax bill. The 2017 TCJA law also reduced the tax to repatriate foreign earnings to 15.5 or 8%, which is below the new corporate tax of 21%. So, despite all of the ballyhoo about investing in the U.S., I don’t see any reason that American multinational corporations will invest in the U.S., much less bring production back from overseas.

If the increased profits they receive from reducing their corporate taxes from 35% to 21% was not enough incentive to seriously increase capital investments, then one has to wonder if these corporations are really serious about investing in the country and its workers. Or, if the long-term game is to continuously shift production overseas and to increase their return on investment from overseas operations rather than US operations.

This is an even more pressing problem in manufacturing than other sectors of the economy, because manufacturing requires so much more investment in equipment, structures, and research and development to grow.

The implementation of the TCJA was a tremendous victory for promoters of supply side economics. The assumption is that if the government reduces taxes, the companies will use the extra profits for capital investments which will lead to growth, hiring more employees, and higher wages. The supply side's theoreticians have been making these claims since the Reagan administration in the early 1980s.

Instead of increasing growth and investment, it appears that the tax cuts will increase the federal deficit, because of declining tax receipts.

One wonders how many times we must accept supply-side solutions before we wake up to the reality of demand-side economics.

Michael Collins is the author of Saving American Manufacturing.