How the Financialization of America Hurt Workers and the Economy

IndustryWeek's elite panel of regular contributors.

Prior to 1980, the financial industry’s role was to fund business and enable investment. But over the years, a new financial strategy has emerged: financialization. It is defined by University of Iowa history professor Colin Gordon as the “growing scale and profitability of the finance sector relative to the rest of the economy, and the shrinking regulation of its rules and returns.”

It began with deregulation and slowly grew to create changes in tax, trade, regulatory and corporate governance law and policy. Financialization is about shareholder value and short-term profits and is based on speculation, risk and debt to enrich investors. This article will show how financialization and the quest for short-term profits has permeated all American corporations.

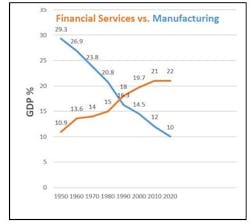

The following chart shows that the finance industry grew from 10% of GDP in 1950 to 22% by 2020. The disproportionate growth of finance diverted income from labor to capital. At its peak in the mid 20th century, manufacturing had 40% of all profits and 29% of the nation’s jobs. Today, finance has 40% of the nation’s profits with 5% of the jobs. One of the big problems caused by finance rising and manufacturing sinking is that a low-employment industry replaced a high-employment industry.

Financialism is totally about making money from money and has nothing to do with creating jobs or shared prosperity.

Growth of Debt

Debt is the lifeblood of financialization. It is where the finance sector makes the most money. According to the U.S. Federal Reserve, , total household and business debt has had phenomenal growth, increasing from from $2.4 trillion in 1974 to $54.3 trillion in 2019.

What is emerging is a new kind of speculative bubble based on consumer and corporate credit. In the last four decades, most of the increase in wealth went to the top 10% of all earners and the other 90% maintained their consumption by borrowing. There is a strong correlation between the rich getting richer and the other 90% going deeper into debt.

The debt picture has also changed for corporations. Corporate borrowing was around 4% of GDP between 1960 and 1990. Between 1994 and 2019, business debt rose from $3.8 to $16.0 trillion. Because of super-low interest rates, debt is accumulating in oil fracking, student loans, investment-grade corporate bonds, private equity firms, hedge funds, mortgage companies, institutional leveraged loans and multinational corporations borrowing to finance stock buybacks. It is all reminiscent of the dot.com bubble in the late ‘90s and the toxic mortgage bubble in 2008. Since the lifeblood of financialization is debt, it begs the question: Is the financial sector setting us up for another financial collapse?

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “one of the major causes of the Great Recession was the excessive amount of risky debt in home-mortgage markets and the resulting financial crisis.” What seems to be emerging is a new speculative bubble based on consumer and corporate credit.

A study by the World Bank found that countries whose debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 77% for prolonged periods experience significant slowdowns in economic growth. According to the U.S. Bureau of the Fiscal Service, in Dec. 2020, the U.S. had a debt-to-GDP ratio of 128.1%. This compares what a country owes with what it produces and is an indication of its ability to pay back its debt. The higher the debt-to-GDP ratio climbs, the higher the risk of default. America is now a debtor nation sinking slowly into deeper debt, and I wonder why more people aren’t concerned.

Capital Investment

Research from the Roosevelt Institute, a left-leaning think tank, shows that productive corporate investment disappeared in the last 30 years and has been replaced by shareholder payouts.

The research showed that in the 1960s and ‘70s, every dollar of earning or borrowing was associated with a 40-cent increase in investment back in the business, versus payouts to shareholders. Since the 1980s, less than 10 cents of each borrowed dollar is investment.

If we are going to be competitive in the world, then we must promote the manufacturing sector and invest more in the research and manufacturing of the new technologies and products that will allow the U.S. to compete. This means investing in capital equipment, research and development, basic science research and start-up companies for the long term. This won’t happen as long as the financial sector is in charge

Supporters of financialization make the case that financialization is the final or perfect form of free-market capitalism where profits are realized the quickest, costs are minimized and the government is not allowed to interfere in the process. Financialization is about making short-term profits and cutting costs to satisfy high-risk investors looking for quick returns.

The argument in this article is that financialization is not a good long-term strategy for the country or the economy. It is no coincidence that the rise of financialization has happened during the decline of manufacturing, middle-class income and capital investment, and the rise of inequality. It is also no coincidence that during the same period there was an enormous shift in wealth to the top 10% earners at the expense of the bottom 90%.

Financialization is about risky trading and the return on net assets that benefits its shareholders but not the parts of the economy that could lead to long-term growth. Financialization is not a good long-term strategy for manufacturing or the economy.

The financial sector used to be the servant of business, which funneled money into productive enterprises. Today they are the masters who dictate to business. They are creating a debt bubble that could lead to another financial collapse and bailout. We ignore it at our peril.

Michael Collins is the author of a new book, “Dismantling the American Dream: How Multinational Corporations Undermine American Prosperity.” He can be reached at mpcmgt.net.